The list of Australia’s top ten Test wicket-takers reads like a concave of the game’s immortals. There are four members of the side that many consider to be the greatest of all Test teams: Shane Warne, Glenn McGrath, Brett Lee and Jason Gillespie, coming in at numbers one, two, six and eight respectively. There are two from more current times, Nathan Lyon and Mitchell Johnson, at four and five. There is one from just before the era of greatness, Craig McDermott at seven. The incomparable Dennis Lillee weighs in at number three. The multi-faceted Richie Benaud is at number nine; for many years, until overtaken by Lillee, he was Australia’s leading wicket-taker, with 248. And just behind him, with 246, is Graham McKenzie.

McKenzie played fewer Tests – 60 – than anyone else in the top ten; this is hardly surprising as he is tenth. His average – 29 – is higher than anyone else’s except Lee (30). His economy rate (2.48) is lower than anyone else’s except Benaud (2.10); but that may just be a consequence of the nature of Test cricket in the 1960s. More interestingly, McKenzie took five wickets in an innings sixteen times; the same as Benaud, and exceeded only by Warne, McGrath and Lillee. Three times he secured ten-wicket match hauls; equalled by Johnson and bettered only by Warne and Lillee.

McKenzie, right arm fast medium, and one of the first Western Australians to flourish at Test level, played for Australia between 1961 and 1971. This was the era after Ray Lindwall (228 wickets in 61 Tests at an average of 23) and before Lillee (355 wickets in 70 Tests at 23), two fast bowlers whose careers seem to be remembered more than his. This must be at least partly because, like most great pace bowlers, they hunted in pairs. It was Lindwall and Miller, Lillee and Thomson. But McKenzie and….?

At the very start of his career he was lucky to be partnering the richly talented left arm swing bowler Alan Davidson (186 wickets in 44 Tests at an average of 20). In his first season of Sheffield Shield cricket McKenzie had been identified by the West Indies captain Frank Worrell, among others, as one destined for great things. He was still a teenager when picked to tour England with Benaud’s side in 1961.

He made an unexpected debut in the second Test at Lord’s, replacing the injured Benaud and being confronted with a pitch that was tailor-made for pace bowlers (featuring the celebrated “ridge”). It was a sensational debut for McKenzie, who turned 20 in the course of the match.

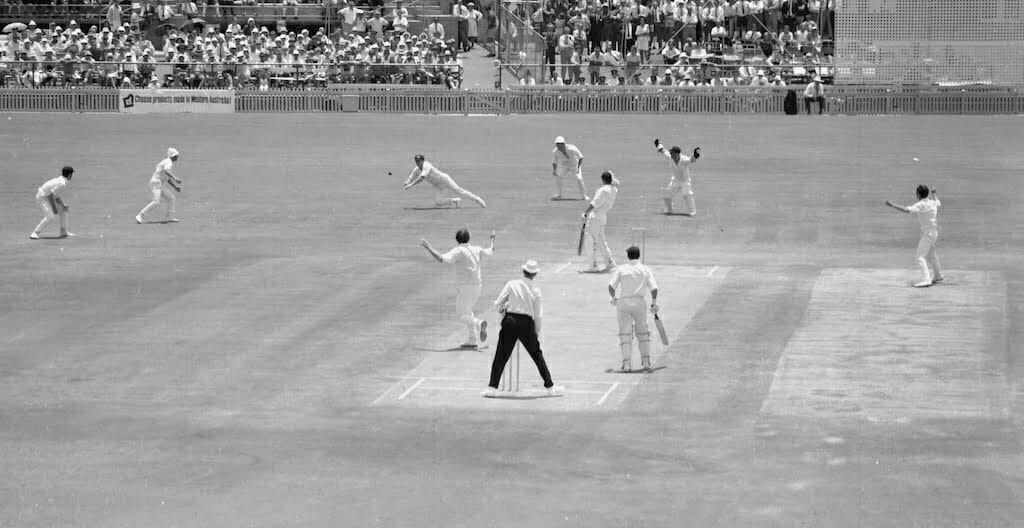

The first match had been a high-scoring draw. At Lord’s, Colin Cowdrey won the toss, for the ninth time in succession, and batted. England made 206. When Australia’s eighth wicket fell on 238 the sides looked evenly matched. But McKenzie joined Ken ” Slasher” Mackay and put on 53 for the ninth wicket. McKenzie and Frank Misson then added another 49 and Australia had a lead of 136. In a relatively low scoring match this was immense. In England’s second innings McKenzie removed the two best batsmen, bowling Ted Dexter for 17 and having Peter May caught behind for 22. He took the last three wickets in the space of twelve balls and finished with five for 37 off 29 overs.

England won the third Test at Headingley, and the teams re-grouped at Old Trafford for what turned out to be one of the classic Ashes encounters. McKenzie was to play a crucial role in this game too. Australia were bowled out for 190 in their first innings, and England responded with 367.

At the start of the fifth day the match, and the series were in the balance; Australia were 150 or so ahead, with four wickets left. The game was going to be won, and lost, in that opening session. Almost immediately three wickets fell to the off-spinner David Allen. McKenzie went out to join Davidson. The pair added 98 for the last wicket (McKenzie 32). Davidson went after Allen and May removed him from the attack; none of the other bowlers made an impact. England had to make 256 in just under four hours. A magnificent 76 from Dexter took them to 150 for one but then a famous spell from Benaud gave victory to Australia by 54 runs. The Ashes were safe.

McKenzie’s contributions to both these games was critical and it says a lot about his temperament that he was able to respond in the way he did, particularly with the bat, in such tense situations at such an early stage in his career.

As a bowler he was not yet the finished product. He was fast and hostile, extracting a lot of lift, but was erratic in direction. This remained the case when Australia next played a Test series, against England in 1962-63. McKenzie took 20 wickets in the series. One of his many considerable qualities was being confirmed; his ability to bowl long spells without losing any of his pace. In the drawn second Test at Adelaide, when Davidson pulled a hamstring early on, he took five for 89 in 33 (eight ball) overs. Another characteristic that was emerging was that his pace, lift and late outswing meant that he was able to trouble the best players, even on good pitches. His five victims at Adelaide included the opener Geoff Pullar, Cowdrey, Dexter and Tom Graveney.

Davidson retired at the end of that series and after that McKenzie was the undoubted leader of the attack. He had a number of highly regarded partners, of whom Neil Hawke a d Alan Connoly were the best, but none was more consistently threatening than McKenzie on his day.

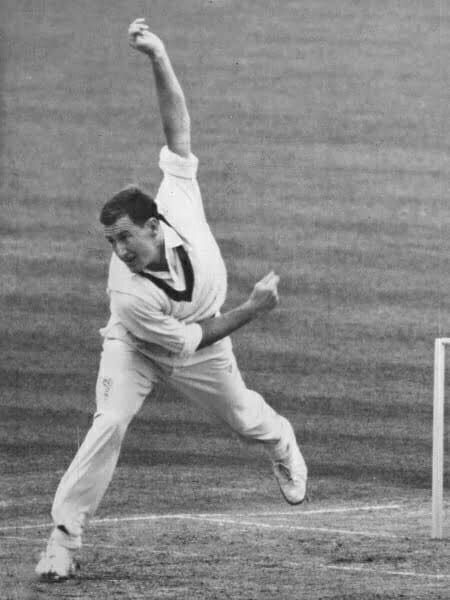

Universally known as “Garth”, after a popular cartoon character noted for his substantial physique, McKenzie was about six feet tall and perfectly built with massive shoulders. He had a smooth, rhythmic and quite short run up – just nine loping paces, a great leap into a classic side on delivery and then a powerful follow through. it was his body action that generated the pace. McKenzie himself has said that at his peak he operated in the 140s (kph) and would sometimes hit 150. As he matured his direction got better and he developed clever changes of pace. His classic ball was the outswinger but he could make it go the other way. Given his ability to bowl long spells he really was a captain’s dream.

He reached that peak on the tour of England in 1964. Again, it must be a factor in his reputation that this is, perhaps deservedly, one of the least fondly recalled Ashes series. It was badly affected by the weather; there was only one definite result, Australia winning the third Test at Headingley. McKenzie was a constant threat to the English top order, finishing with 29 wickets at 22 apiece. He took seven in the match at Headingley, an unusual Test in that the decisive contribution came from a batsman, the pugnacious Peter Burge making 160 in Australia’s first innings.

The series reached its nadir in the fourth Test at Old Trafford, the only game blessed with decent weather. Having won the third, Australia’s captain, Bob Simpson, figured England would need to win both the last two games to recover The Ashes. He won the toss at Old Trafford and batted – and batted. Australia made 656, Simpson himself making his first Test hundred -311. England responded with 611, Ken Barrington making 256. The off-spinner Tom Veivers bowled 95 overs. And McKenzie? He took seven for 153 in 60 overs.

On their way home from England – this seems incredible now – Australia played four Tests in India and Pakistan. They won the first in India, at Madras; McKenzie six for 58 in 32 overs in India’s first innings. The three-match series was drawn. In the one-off game in Karachi, a draw, he took six for 69 in 30 overs.

McKenzie finished the calendar year of 1964 with 71 wickets, beating a record that had stood since 1912. The record remained his until it was broken by Kapil Dev in 1979.

It was clear that, with the retirements of Davidson, Benaud and Neil Harvey, Australia were not the force they had been. As the decade wore on victories became rarer and they seemed to depend very much on an outstanding performance from McKenzie. A hard-fought series in the Caribbean in 1965 saw the West Indies emerge as 2-1 winners; Australia won the final Test at Port of Spain by 10 wickets. McKenzie took five for 33 in 17 overs in the second innings, including a spell of three wickets in four balls. He had an unproductive start to the 1965-66 Ashes (like the 1962-63 instalment, a 1-1 draw). In fact, the selectors dropped him for the fourth Test at Melbourne. Injury to another bowler meant a reprieve. He took six for 48 in England’s first innings and Australia won.

He was one of the few successes of a difficult tour of South Africa in 1966-67, when Australia lost 3-1. He took eight wickets in Australia’s win in Cape Town, including five for 65 in the first innings. Altogether he took 24 wickets in the series at an average of 26. in the home series against India a few months later he suffered the unusual experience of being dropped for doing too well. In the second Test at Melbourne he took seven for 66 and three for 83; Australia won by an innings to go two-nil up. McKenzie was “rested” for the remainder of the series. Australia still won four-nil.

But intimations of mortality were becoming more frequent. There was a difficult tour of England in 1968, when both he and Hawke were too erratic. The home series against the West Indies in 1968-69 saw a return to form; 30 wickets in the series at an average of 25, and eight for 71 on a chilly Boxing Day at Melbourne where Australia went on to win by an innings.

At this point McKenzie took a decision which had a considerable impact on his career. Cricket was in effect an amateur sport in Australia. Many players retired quite young, to forge a career elsewhere. McKenzie we t down a different route; he became a professional for Leicestershire in 1969, the same year Ray Illingworth signed as captain. This meant McKenzie was playing cricket all year round.

In his first year McKenzie took 74 wickets at 21 apiece; he “did not quite come up to expectations”, as Wisden rather grudgingly put it. (Fourteen bowlers averaged under twenty that year and four of them took over a hundred wickets.)

In the Australian summer of 1969-70 the national cricket team played nine Tests; five in India, the fifth starting on Christmas Eve; and four in South Africa. They won the first series 3-1. But it was a difficult series in many ways – uncomfortable, poorly rewarded and before large and often potentially riotous crowds. For McKenzie it saw some notable achievements. Despite the adverse playing conditions – for a bowler of his type – he played a critical role in each of the wins, again and again summing up that extra special something to rip through the top order. He took 28 wickets at an average of 20. Few visiting fast bowlers can have achieved such figures in India. (In 1983-84 both Malcolm Marshall and Michael Holding took 34 wickets at under 22.)

But the price was a high one. McKenzie lost six kilos in India and felt desperately lethargic when the team went to South Africa. Within a month of finishing the fifth Test at Madras the tourists were facing South Africa in Cape Town. Australia lost four-nil. McKenzie took one wicket for 333 runs.

It wasn’t quite the end. He had a very good summer for Leicestershire in 1970 and started in the Australian team that faced Illingworth’s Tourists in 1970-71. He played in three Tests, including fittingly, the second, at Perth, the first to be played at The WACA, where he took four wickets in England’s first innings. He played his last match at Sydney, and retired hurt when a bouncer from John Snow hit him in the face. By the sixth Test, at Adelaide the bowling was being opened by another Western Australian, Lillee. “Garth” had been his boyhood hero.

From Alan Davidson and Wally Grout to Dennis Lillee and Rod Marsh. It was quite a transformation. McKenzie has said that he wished he had been on the 1972 tour, with Lillee and Bob Massie – he was still bowling very well for Leicestershire. He has also said he wished he could have bowled with McGrath. As a bowler he was up there with any of them. But the world they operated in – especially after World Series Cricket – was a different one. There was something more old-world and appealing about this quiet and undemonstrative man. No sledging for him.

He carried on for Leicestershire for a few more years after his international career ended. Under Illingworth the side gradually improved and finally won the Championship for the first time in 1975. That turned out to be McKenzie’s final, and by some distance his least productive, season with the county.

He said the best players he bowled to were Graeme Pollock, Barry Richards and Gary Sobers; they could take you apart. Players like Barrington might bat all day but they didn’t worry you in the same way. Cowdrey commented that McKenzie was able to discomfort the best players in apparently comfortable conditions.

One of his great contemporaries, Geoffrey Boycott, was frequently discomfited. He had his arm broken by McKenzie at Perth in 1971 – after he had helped England win The Ashes. There are a number of other references in Boycott’s autobiography to his being troubled by McKenzie. He fractured the skull of West Indies wicket keeper Jackie Hendricks in 1965. But it was all done almost apologetically.

‘“Some people said I was too nice to be a paceman”, he told Brydon Coverdale in an interview. Somebody else put it better: “He was the Rolls Royce of fast bowlers.”

Bill Ricquier