Nobody thought it at the time – though the result of the final was surprising, almost sensational – but the 1983 Prudential World Cup was the single most significant cricket tournament in the game’s history.

India had never seemed to be that bothered by one-day cricket. That all changed with their totally unexpected victory over the all-conquering West Indies at Lord’s. All of a sudden, the whole, vast country loved the limited overs game. Almost everything that has happened in cricket since, including India’s financial ascendancy and the IPL, can be traced back to World Series Cricket, and India’s victory in the 1983 World Cup.

The tournament was the third World Cup, and the third to be played in England. There were eight contestants, divided into two groups, but unlike the two earlier versions, in 1975 and 1979, each team played each other group member twice. So, there were 27 matches played between 9 and 25 June.

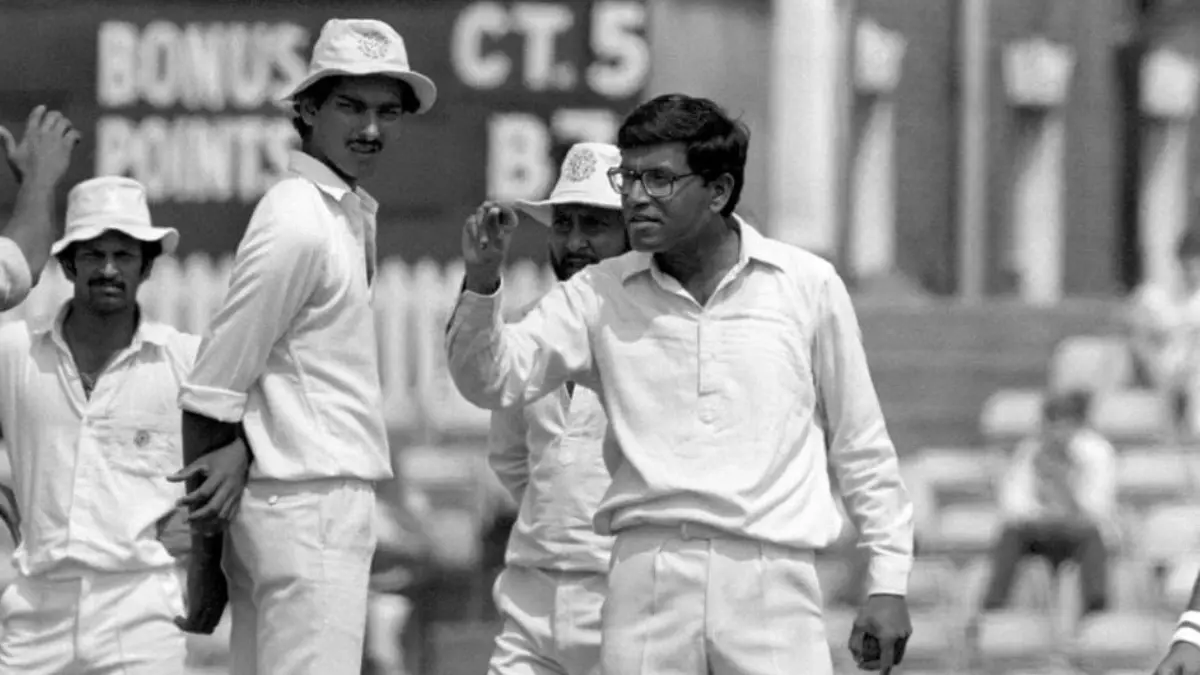

India were a surprise package right from the start. They surprised the West Indies in their first group game at Old Trafford, winning by 34 runs, Yashpal Sharma making 89 and Ravi Shastri and medium pacer Roger Binny taking three wickets each.

West Indies got their revenge at The Oval, where Viv Richards made 119. India’s next game, in Tunbridge Wells against Zimbabwe, whom they had beaten easily enough at Grace Road, Leicester, was one of the most sensational of all World Cup encounters. India won the toss and batted and were soon nine for four. That was when captain Kapil Dev went to the crease. Soon it was seventeen for five. The eventual total was 266 for eight, with Kapil making 175 not out, with six sixes and 16 fours. Kevin Curran (the father of Tom and Sam) who had taken three wickets, batted well for 73, but India won by 31 runs.

With West Indies invincible after that early setback, qualification from Group B became fairly predictable. Australia were below par, managing to lose to Zimbabwe at Trent Bridge (Duncan Fletcher 69 not out and four for 42).

Group A was slightly more open. Bob Willis’s England breezed through, losing only one game, a close encounter with New Zealand at Edgbaston. Sri Lanka were always likely to struggle, though they beat New Zealand in Derby, thanks to a classy 64 not out from Roy Dias (and Ashantha de Mel was the competition ‘s joint highest wicket taker, with Binny). That left Pakistan and New Zealand, and although the former’s captain couldn’t bowl due to injury, they were generally a more effective unit.

The semi-finals

England’s dream of reaching a second successive final were ended at Old Trafford by the underrated Indians. England started well enough with Graeme Fowler and Chris Tavare putting on 69 at four an over (perhaps no single selection illustrates the difference between limited overs cricket in 1983 and 2019 – the World Cup was still a 60-over tournament then – than the choice of Tavare to open). But after the medium pacers came on – Binny, Mohinder Amarnath, Madan Lal – the batsmen just list their way. No one made more than Fowler’s 33 and a total of 213 was never likely to be enough. India won by six wickets with almost five overs in hand, Yashpal making 61 and Amarnath 46 not i

out.

In the other semi-final West Indies made short work of Pakistan at The Oval. The Pakistan innings never got going. Opener Mohsin Khan was eighth out for 70, but there were only two boundaries in the entire innings of 184 for eight. Even the “fifth bowler” – a combination of Richards and Larry Gomes – conceded fewer than four an over. West Indies strolled to victory by eight wickets in 48.4 overs. Richards finished unbeaten on 80, and Gomes 50.

The final

Almost 25,000 were at Lord’s to watch an intriguing contest. if there was ever a game to demonstrate that it is a low scoring encounter that offers the most entertainment, this was it.

Clive Lloyd won the toss and invited the Indians to face the testing pa e of Joel Garner and Andy Roberts. Sunil Gavaskar fell early but there was a brilliant counter-attack from Kris Srikkanth and more solid, sensible batting from Amarnath. India were 100 for four at lunch. Kapil failed but the tail, in particular the wicketkeeper Syed Kirmani, fought hard. Still, 184 did not seem enough.

That feeling was reinforced as Richards eased his way to 33. Then he miscued a hook off Madan Lal and the ball flew high in the direction of deep midwicket; Kapil had to make a lot of ground running backwards and caught it. It was one of those very critical moments – not just the quality of the catch but the fact that it came out of nowhere. Very special cricketers are capable of these things. Ben Stokes is a modern example: Kapil was that sort of cricketer.

Suddenly, well, India were in with a chance. Desmond Haynes and Gomes were soon out: that was three wickets for six runs. And the relentless plod of India’s medium paced trundlers carried on.

West Indies were all out for 140. Amarnath (26, and three for 12 in seven overs) was man of the match, as he had been in the semi-final. But Kapil was the hero. And Indian cricket was never the same again.