On BBC’s Test Match Special Michael Vaughan and Graeme Swann separately described the delivery from Mitchell Starc that dismissed James Vince in England’s second innings in the third Ashes Test at the WACA as “the ball of the century”.

It was certainly a remarkable ball. Vince was well set and batting beautifully. Starc had gone round the wicket, coming in quite wide on the crease and clearly targeting the cracks that were widening on a length. The ball in question hit one of those cracks as it pitched on off, and, instead of continuing on its path and passing outside leg, which Vince was clearly expecting, it straightened, like a high- velocity leg break, and flattened the off stump.

It was an unplayable ball. But is it a bit over the top to call it the ball of the century?

One would think that context has to be taken into account in establishing such a claim. At the WACA, England were simply not in the game. When the ball was delivered, England had already lost both openers and the captain Joe Root, and still had a deficit of 159, with over a day still to bat to save the game. Vince always seemed an unlikely saviour. His apparently uncontrollable fondness – almost a fetish – for fiddling outside off means that disaster always seems just around the corner. Actually he played wonderfully well but to call his dismissal a series-changing, or even a game-changing moment would be an exaggeration.

Earlier in the year there was another possible candidate, also from a left-arm paceman. This came in the Champions Trophy final at The Oval between Pakistan and India. Pakistan batted first and made 338 for four, which was always going to be a competitive target. But it was not inevitable that it was a winning total because leading India’s response was perhaps the greatest one -day chase artist of all time, their captain Virat Kohli. Kohli was in in the first over because Mohammed Amir trapped opener Rohit Sharma leg before with the third ball of the innings.

Off the third ball of his second over Amir had Kohli dropped by Azhar Ali at slip. This could have been a seriously bad moment for Pakistan. But Amir came back with a beauty: also on off, also moving slightly away. Kohli, aiming to turn it to leg, got a leading edge and the ball went straight to Shadab Khan at point. No mistake this time and the feeling that India’s fate had been sealed turned out to be justified.

Amir’s ball was not in the same unplayable category as Starc’s. But one suspects it will be remembered long after Starc’s is forgotten. There was of course the match situation; that was enough to make the ball and Amir’s spell, memorable. But there was so much more to it than that. This was an international final, in a tournament for which Pakistan had seemed fortunate to qualify and in the early rounds of which they had barely seemed to turn up. Now, after years of isolation in the UAE, they were competing in a global final in London. And, even though it wasn’t a World Cup, it wasn’t any old final. It was a final against India. The resonance was immense.

Moving centuries for the sake of analogy, it was noteworthy that many pundits compared Starc’s delivery to Wasim Akram’s ball to Allan Lamb in the 1992 World Cup final in Melbourne in 1992. Wasim was of course, like Starc and Amir, a left arm fast bowler. It is probably too early to compare the other two with this genuine master, a bowler reckoned by many of his contemporaries to be the most demanding they ever faced. Together with the Australian Alan Davidson, he has been the greatest of all left arm pacemen.

In some ways it was odd to find Starc’s ball being compared with Wasim’s. The Kookaburra ball, used in Australia, is notoriously impervious to efforts to swing it, including Starc’s. The so-called ball of the century was bowled dead straight; its magic came from Starc’s ability to hit the crack at high pace. Wasim, on the other hand, was in the Benny Goodman class when it came to swing.

Pakistan had made 249 for eight at Melbourne and England were struggling at 69 for three when skipper Graham Gooch was out. There followed a determined and spirited stand between Lamb and one-day specialist Neil Fairbrother, who took the score to 141; 109 to win in fifteen overs. At this critical juncture Imran Khan brought Wasim back on.

He took two wickets in that first over. With the fifth ball he bowled Lamb. Tony Cozier, commentating on television, said it was as close as you could get to unplayable. Like Starc, Wasim was coming round the wicket to a right-handed batsman. Like Vince, what Lamb had to contend with was effectively a fast leg -break. But Wasim’s ball wasn’t dead straight. It swung in towards leg stump before jagging back to hit the top of off. Next ball Wasim bowled Chris Lewis with an extravagant in-swinging yorker, but it was the Lamb dismissal that created the legend. Again, the match situation and the nature of the global competition gave the ball that special lustre.

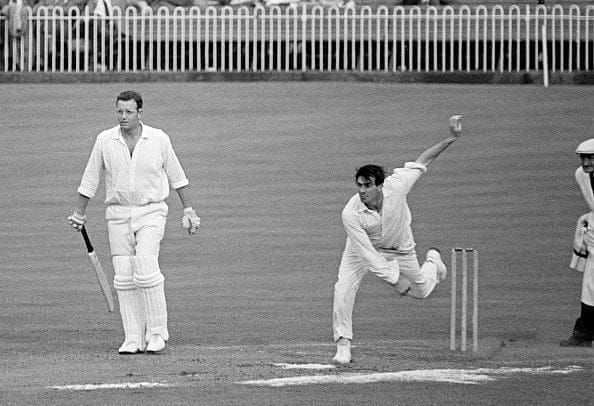

Fifteen months or so later came the actual, more or less universally acknowledged, ball of the (twentieth) century. It was bowled by Shane Warne in England’s first innings of the first Ashes Test at Old Trafford in 1993. The apparently unsuspecting victim was the experienced middle-order batsman and former captain Mike Gatting.

It is hard to believe there is anyone reading this who has not seen That Ball a few times. Like an episode of Fawlty Towers – but in much less time – it never fails to hit the spot. Warne’s action was riveting, and unique. The purposeful walk, turning into a three or four pace run; the powerful twist of frame and of wrist as the arm went over. He was going round the wicket to Gatting. The amount of revolutions on the ball meant it drifted to outside leg stump, and also dipped, confounding the batsman as to both line and length. Gatting just plunged his front foot in the general direction of the ball, which spun past unimpeded and hit the topof off stump. Gatting genuinely had no idea what was going on. (Australia won the six-match series four-one.)

The ball unquestionably deserved its billing. The extraordinary nature of Warne’s unique talent meant that one became almost accustomed to his producing huge spinning and very accurate leg breaks. About two overs after the Gatting ball he bowled a similar one to dismiss Robin Smith. Of course the amazing thing about the Gatting ball was that it was Warne’s first against England. The mental impact was immense. Almost fifteen years later, in 2006-07 Warne retained a psychological hold over England batsmen that enabled him to win a Test match – in Adelaide – almost single-handed.

In 1948 another leg-spinner bowled a ball in an Ashes Test that became one of the most famous of all cricketing images. This was Eric Hollies’ dismissal of Don Bradman for a second-ball duck in Australia’s only innings in the fifth Test at The Oval. The ball, a googly, was hardly unplayable. But it was good enough to beat the greatest batsman of all time on the day. Australia won the match by an innings and plenty.

Could there be a candidate for ball of the century that did not take a wicket? Perhaps, in the case of one sort of ball. In the current Ashes series there have been murmurings about intimidatory bowling by Australia’s fast bowlers at the English tail. When this sort of topic comes up, especially in an Anglo – Australian context, it can only mean one thing.

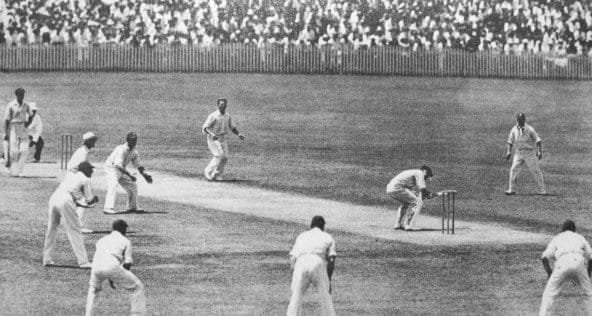

Douglas Jardine’s MCC side that toured Australia in 1932-33 had a mission. It was to prevent a repetition of 1930, when Bradman scored 974 runs in seven innings. The method chosen was simple, brutal and effective. It was to adopt a policy of fast, short-pitched bowling directed at the upper body, with a packed leg-side field. The batsman’s options were limited: hook and/or pull (brilliantly accomplished by Stan McCabe in his 187 in the first Test at Sydney); defend, and risk being caught by the ring of close leg side fielders; duck; or get hit.

Jardine had the ideal raw materials for this venture in the very fast and very accurate Harold Larwood and his Nottinghamshire team-mate the left armer Bill Voce. The tactic worked in that England won the series and Bradman averaged around fifty.

Australian cricket batsman Bill Woodfull faces a Bodyline field in the 4th Test match in Brisbane, 1933. Harold Larwood is bowling. From Wikipedia; Copyright has expired.The recriminations and the consequences were deep and long-lasting. The series reached its nadir, in terms of the relationship between the sides, in the third Test at the Adelaide Oval. On the second afternoon Larwood was bowling to the captain Bill Woodfull. He fizzed a bouncer past his nose and then a shortish ball on middle stump hit Woodfull over the heart. Woodfull staggered and doubled up in pain. “Well bowled Harold!” came Jardine’s patrician boom. A Bodyline field was assembled as Woodfull recovered his composure. The barrage continued. Another ball from Larwood knocked the bat out of Woodfull’s hand.

After play, an incident occurred that was really the genesis of the Bodyline sensation as we know it. The MCC manager, Pelham Warner, himself a former Ashes-winning captain, visited the Australian dressing -room to enquire after Woodfull’s health. The Australian captain’s response has gone down in history as one of the most acerbic and significant quotations in sport: “I don’t want to see you Mr Warner. There are two teams out there. One is trying to play cricket and the other is not.”

To this day nobody is sure who leaked the story of the exchange between Warner and Woodfull to the press. One suspect was the opening batsman Jack Fingleton, a professional journalist, but he always denied it. Bodyline accentuated a sharp divide in the Australian side between what one might call the Establishment, led by Bradman, and an influential Irish Catholic group led by Fingleton and the leg-spinner Bill O’Reilly. (E W Swanton told David Frith, author of Bodyline Autopsy, literally the last word on the subject, that Fingleton and O’Reilly broke into uncontrollable laughter in the press box at The Oval in 1948 when Hollies bowled Bradman.)

Whoever leaked the story, it changed the entire flavour of the series, and indeed the relationship between England and Australia. The point was that, until then, nobody outside the Australian team knew what Woodfull, a remarkably courteous and discreet man, really thought about Bodyline. Now the gloves were off, diplomatically speaking.

Cricket-wise, the crisis had two significant consequences, one intensely personal. Larwood, urged by the English cricket hierarchy to apologise, refused to do so, and never played Test cricket again. And the Laws changed, restricting the number of fielders behind square on the leg side.

Of course the very idea of a ball of the century is nonsense really. As with all these things there must be an element of luck, almost of fluke. If Vince had managed to get a bit of bat on that ball from Starc and it had flown between keeper and slip, no one would have remembered it. Warne always had his huge leg breaks, but by the end of his career he was taking lots of wickets with balls that went straight on. And people always exaggerate. Even at the time Bob Willis said the Gatting ball turned two and a half feet; in fact it was about nine inches.

After a successful day’s cricket, the great Yorkshire and England fast bowler Fred Trueman would tell anyone within earshot about his performance. John Arlott tells the story of one such recounting, after an innings win against Leicestershire in 1968. One batsman had been yorked, one had nicked an outswinger, etc. Team-mate Richard Hutton interrupted. “You must have bowled the lot Fred – inswing, outswing, yorkers, slower ones – but tell me, did you ever bowl a plain straight ball?” The great man didn’t miss a beat. “Aye, I did, to Peter Marner. It went straight through him like a stream of piss and flattened all three.”

Bill Ricquier

Featured Image: Leg-Spinner Shane Warne bowls in his final Test against England in Sydney, 2006, 13 years after he bowled Mike Gatting with “That Ball” at Old Trafford. Photo Mac Coates

This article first appeared in scoreline.asia