Rangana Herath did something remarkable in Sri Lanka’s comfortable win over Bangladesh in the second Test at Mirpur. In taking his 415th Test wicket, in his eighty-ninth match, he overtook Wasim Akram, who had taken 414 wickets in 104 matches, to become the most prolific left-arm bowler in Test history.

As it happens, another Sri Lankan, Kumar Sangakkara, is Test cricket’s most prolific left-handed batsman, with 12,400 runs at an average of fifty-seven. His great contemporary, Mahela Jayawardene, made the highest Test score by a right hander, 374 against South Africa in Colombo in 2006, in the course of which he put on 624 for the third wicket with Sangakkara, the highest partnership in Test history.

Of course the record books looked very different then, mainly because of the dominance that history and the regularity of The Ashes had afforded England and Australia. Of the ten highest scoring Test batsmen as of 31 October 1964, only one, the Barbadian Everton Weekes, came from outside those two countries. Rather more surprisingly, perhaps, there was only one left-hander, Australia’s Neil Harvey. With the bowlers, it was a similar story. Only the fact that there was a three-way tie for tenth place, with 170 wickets, accommodated the inclusion of a non-Englishman or Australian, South Africa’s Hugh Tayfield, and a left-arm bowler, Tony Lock.

By 1981, immediately before Sri Lanka’s admission to the Test ranks, things were beginning to change. Test cricket’s leading run-scorer and wicket-taker were both from the West Indies, Gary Sobers and Lance Gibbs. This meant there were now two left -handers in the top ten batsmen – Harvey was still there – and Sunil Gavaskar and Rohan Kanhai joined Sobers as interlopers from cricket’s new world. Of the top ten bowlers seven came from England and Australia, including left-armer Derek Underwood, and there were two Indians, including left-armer Bishan Bedi; the multi-talented Sobers was eleventh.

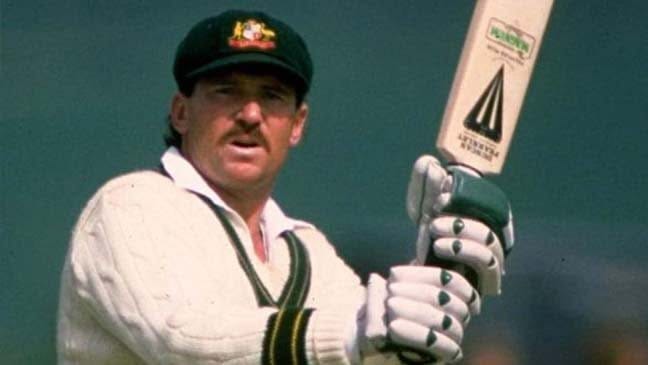

The current situation is quite different again. The ten top-scoring Test batsmen as of today’s date come from six different countries (counting Trinidad and Tobago, and Guyana, as one for this purpose) and include two Australians – Ricky Ponting and Allan Border, and one Englishman, Alastair Cook. And there are five left-handers. The top ten bowlers come from seven countries – New Zealand have always played fewer Tests than the other “older” countries and Sir Richard Hadlee’s position in this group is testament to his exceptional prowess. But there are no left-armers. Herath comes in – currently – at number twelve.

In any form of human activity one would expect to find more right-handed than left-handed practitioners. This is the case with cricket, notwithstanding the fact that, as a game where angles are critical, left-arm bowlers and left-handed batsmen present special challenges to their opponents, particularly when paired, as they normally will be, with a right-handed team-mate. There is an additional complication with batting in that the top hand is the dominant one (for most purposes, at least in the longer formats) so that a right-handed batsman might well be a natural left-hander. (Ask Sachin Tendulkar for his autograph.)

In days of yore left-handed batsmen certainly seemed rarer. Two of first-class cricket’s greatest run-scorers were Frank Woolley and Phil Mead, who were almost exact contemporaries, with very different styles, but both left-handed. Each enjoyed success with England but they rarely played in the same side. It was as though one left-hander was enough.

In The Oval Test of 1964, when Trueman took his 300th Test wicket, only five left-handed batsmen were playing, including the English fast bowler John Price and the Australian off-spinner Tom Veivers. There were no left-arm bowlers at all. In the equivalent match in 2015 there were nine left-handed batsmen and two left-arm bowlers (both Australian).

Fred Trueman’s 300th Test wicket is towards the end (1’25”) of this great video

In that match all four opening batsmen were left-handers. The mantra is that it is good to have a left-right combination, but historically most of the great pairs were right-handers. Since the 1980s it has been common to have left-handed pairs: John Wright and Bruce Edgar, Aamer Sohail and Saeed Anwar, Matthew Hayden and Justin Langer, Marcus Trescothick and Andrew Strauss.

Also in that 2015 England side three of the English left-handed batsmen bowled right-arm: Ben Stokes, Moeen Ali and Stuart Broad (James Anderson, who is in the same category, was injured). Stokes, if all goes well, may one day rank as one of the great all-rounders. Most of them have been “pure” right-handers – Ian Botham, Imran Khan, Jacques Kallis, etc, etc. An exceptional few have been left-handers: Sobers, Akram, Allan Davidson. “Hybrids” are quite unusual – the Yorkshire pair from Kirkheaton, Wilfred Rhodes and George Hirst, Vinoo Mankad, Ravi Shastri, Lance Klusener.

Left or right is becoming increasingly blurred in the shortest format. Reverse sweeps have been around since the days of Hanif and Mushtaq Mohammad. But in a recent T20 international between Australia and England at the MCG, England’s Sam Billings, a right-hander played a shot that almost went for six over third man. It wasn’t exactly a reverse pull. Even Kevin Pietersen, inventor of the switch hit, was gobsmacked.

“He played that left-handed!!”

Bill Ricquier

Feature image: Rangana Herath Delivers Left Arm over the wicket at Lords – June 2011 – England v Sri Lanka. By Gareth Williams from Redhill, England [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.