England’s mildly catastrophic Ashes series is to be followed by a two-match Test series in New Zealand. On the face of it there is something almost nostalgic about that. MCC historically always sort of added New Zealand on to a tour of Australia. The team travelled by ocean liner, spending weeks at sea; presumably the feeling was that it would be impossible to justify having an entirely separate trip to New Zealand. And part of the justification for that was that New Zealand were somehow the poor relations – the country cousins.

There were ten Ashes series in Australia between 1932-33 and 1974-75, and each of them, except the 1936-37 one, was followed by a series in New Zealand. New Zealand did not win a single game in any of these series but they still managed to draw a number of them nil-all – 1932-33, 1946-47, 1965-66. Nonetheless, most of the memorable individual performances came from the Englishmen.

In 1932-33 Walter Hammond made 336 not out in the second Test at Eden Park, Auckland, hitting ten sixes and making his third hundred in forty-seven minutes. In the first Test, at Lancaster Park in Christchurch, he had made 227. Hammond was unquestionably one of the greatest players of all time (although not worthy of a place in BBC Test Match Special’s all-time composite Ashes Eleven). Hammond’s career, though, was ultimately tinged with disappointment and it was certainly a misfortune that his time in international cricket coincided almost exactly with Don Bradman’s. This innings provides a rare example of Hammond out-doing his rival: he overtook Bradman’s 334 – made at Headingley in 1930 – to compile what was then Test cricket’s highest individual score.

At least New Zealand were spared the ordeal of facing Harold Larwood, the Bodyline destroyer, when Douglas Jardine’s side moved on to New Zealand in 1932-33: he had been injured in the last Test in Australia. There was no such luck in 1954-55 when Len Hutton’s Ashes winners moved south. Frank Tyson, Brian Statham, Bob Appleyard and Johnny Wardle, Hutton’s match winners, we’re all on song in the second Test at Eden Park when New Zealand were bowled out for twenty-six, still the lowest score in Test cricket.

Ted Dexter’s 1962-63 side, which had been slightly underwhelming in Australia, won three-nil in New Zealand. In the first Test at Eden Park Peter Parfitt and Barry Knight put on 240 for the sixth wicket, which remained an English record until eclipsed by Ben Stokes and Jonny Bairstow at Cape Town I in 2015-16. In the second Test at the Basin Reserve in Wellington, Colin Cowdrey and AC Smith put on 163 for the ninth wicket, then a world record and still an English one.

A shell-shocked England went on to New Zealand after losing to Ian Chappell’s Australians in 1974-75. They had won the last Test, when both Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson were effectively hors de combat, and at Eden Park they carried on where they had left off, with captain Mike Denness making 181 and Keith Fletcher 216 as England totalled 593 for six. They won by an innings, but there was a chilling end to this game. The New Zealand number eleven, Ewan Chatfield, deflected a ball from fast bowler Peter Lever into his left temple (no helmet of course). He collapsed unconscious with a fractured skull and received life-saving treatment on the pitch.

In the course of this long period of winless encounters with England, New Zealand began to enjoy success against other opponents. In 1955-56 they achieved their first Test win, the fourth and last Test against the West Indies at Eden Park. West Indies had won the first three Tests (Everton Weekes made a hundred in each of them; he made five and thirty-one at Eden Park.) Their first series victory came in 1969-70 in Pakistan. In the 1950s, although they produced some great players – Bert Sutcliffe and Martin Donnelly were probably, with Arthur Morris, the best left-handed batsmen in the world and John Reid was an outstanding all-rounder – they were still potential whipping-boys. They had a dreadful tour of England in 1958, but through the 1960s, home and away, they drew more series than they lost. Then, in the 1970s, under two inspirational captains, Bev Congdon and Geoff Howarth – and not forgetting Mark Burgess – they began to be seriously competitive.

It is tempting to compare New Zealand’s start in Test cricket with Bangladesh’s but that would be unfair. When New Zealand beat the West Indies in 1955-56, they had had to wait twenty-nine years and forty-five matches for that first victory. Bangladesh played its first Test in 2000, and secured its first victory, against a malfunctioning Zimbabwe, in 2005. That’s just five years. But in that time there were thirty one defeats and only three draws. As of today, Bangladesh have played 106 Tests and won only ten: five against Zimbabwe, two against the West Indies, and one each against Australia, England and Sri Lanka. New Zealand have played 424 matches, winning ninety-one and losing 170. It doesn’t look great, but it is a record that is not seriously comparable to Bangladesh’s.

Bangladesh’s victories against Australia and England have come in the last eighteen months, and although secured in very favourable conditions at home, are perhaps an indication that they are finally finding their feet in Test cricket. When they beat England at Mirpur in October 2016, there was no sense of national disgrace in England, more a sense of inevitability, and of justified foreboding regarding the imminent tour of India.

But when England lose to New Zealand it seems a bit different. It seems somehow to be, at best embarrassing, if not humiliating. It is not immediately obvious why this should be so, although it must be partly explained by New Zealand’s lengthy period of struggle in the international game.

The Test cricket family is, like it or not, linked by the uncomfortable umbilical cord of colonial rule. This does not necessarily mean that there is anything more than a superficial resemblance, or similarity, between the Test playing territories; after all there are striking distinctions even between the Caribbean nations. The two countries on the face of it most similar to one another, due to historical bonds far more fundamental than anything to do with Britain’s imperial past, India and Pakistan, are riven by deep and apparently unbridgeable differences.

The two cricketing nations most similar to – or least different from – one another are England and New Zealand. They certainly have more in common with each other than either has with Australia. A lot of New Zealand looks, if not like England, then at least like Britain. There is the frequently awful weather. There are common values. But New Zealand has a small – almost tiny in modern terms – population, and a very high proportion of the male population is obsessed with rugby. What right, the English seem to think, do they have to be good at cricket? But they are good; for a while in the mid-to -late 1980s, when in Richard Hadlee and Martin Crowe they had two of the greatest players in the world, they could challenge the best. They usually have a great team ethos so that even when there is a shortage of stars there is a feeling that the team is bigger than the sum of. Its parts.

When New Zealand weren’t winning they were popular in England. Many England supporters may well have been quietly hoping that New Zealand would win the first Test at Trent Bridge in 1973, when the visitors made a heroic effort to chase down a target of 478. It was a curious game. England made 250 and New Zealand responded with 97 (Tony Greig four for 35; extras top-scored with twenty). In England’s second innings of 325 (which I watched), most unusually nobody made double figures; Greig and Dennis Amiss made centuries and the next highest score was seven. Congdon led the fight to an elusive victory with 176. Vic Pollard, often a thorn in England’s side on three tours there, scored 116. Home supporters’ whimsical thoughts of a New Zealand win were not tested to the limit: England won by 38 runs. The second Test was a high-scoring draw: Congdon made 175 and Pollard 115 not out. England won the third by an innings.(Pollard had a Chariots of Fire moment when Ray Illingworth’s side toured New Zealand in 1970-71, declining to appear in the Christchurch Test because it included Sunday play.)

The series which most clearly illustrated England’s antipathy to losing to New Zealand was the home series in 1999. The 1990s had been a difficult time for England but it was hoped that with a new captain, in Nasser Hussain, there might be a new beginning. Well, to be fair, there was, but not yet. The first part of the summer had been utterly dismal for the hosts, with an ignominious exit from the World Cup. A four-match series against poor old New Zealand was thought to be just the ticket. And they actually won the first Test comfortably. But then the wheels came off. Hussain broke a finger at Lord’s: New Zealand won that Test by nine wickets. The third Test, at Old Trafford, was if anything even worse. England, led by the relatively inexperienced Mark Butcher, took first use of a difficult pitch and were bowled out for 199. Stephen Fleming, one of the shrewdest captains of his time, declared on 496 for nine, Nathan Astle and Craig Macmillan making confident hundreds. Rain spared the home side from further embarrassment, but it did not spare the selectors; Graham Gooch and Mike Gatting were immediately sacked. New Zealand then won the final game by 83 runs. Losing to New Zealand was bad enough; to make it worse England were now bottom of the Wisden Test Championship.

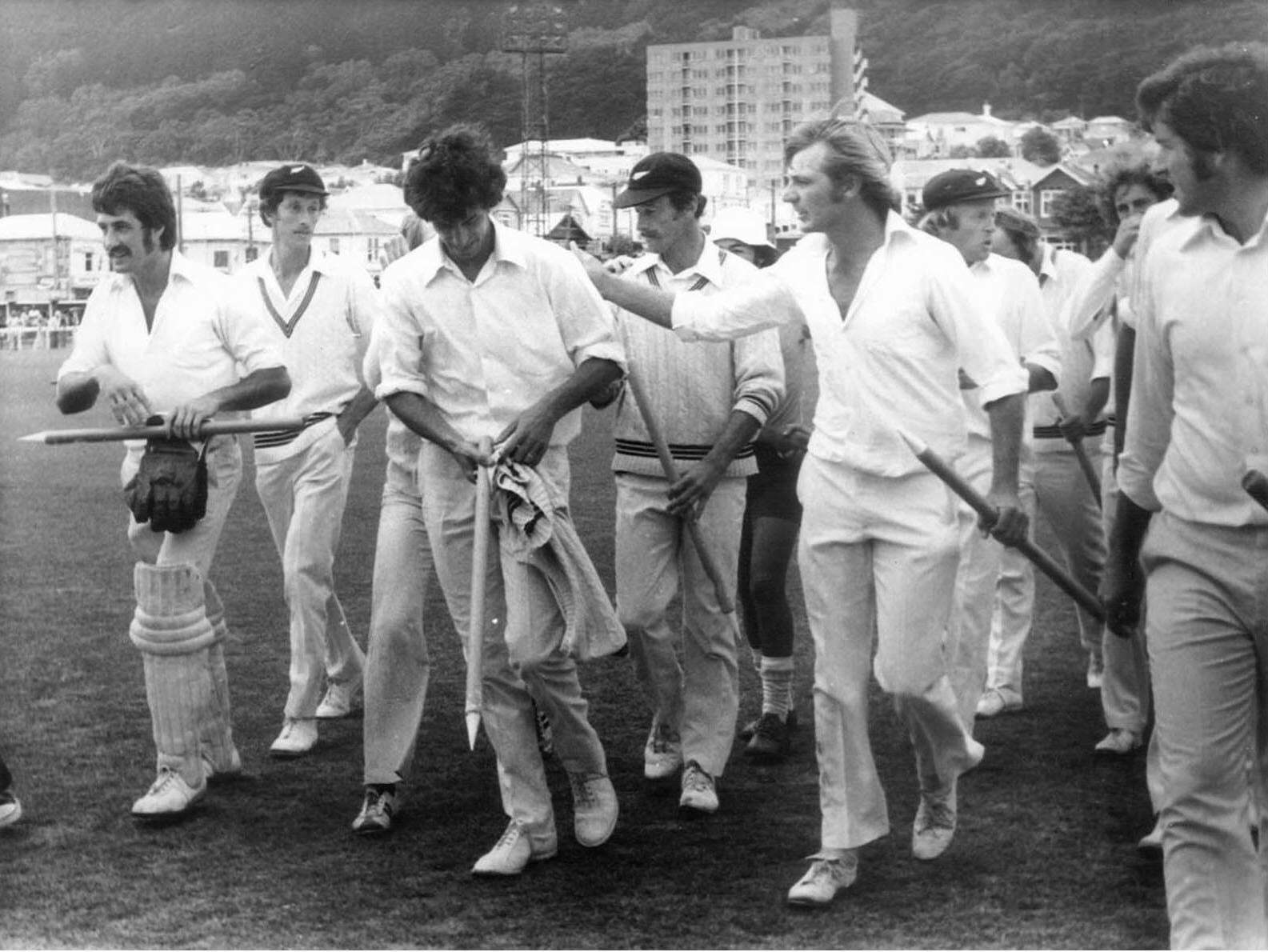

New Zealand’s first win against England had come at home in 1977-78, England’s first tour of New Zealand not tacked on to the back of an Ashes series since 1929-30. It was the first English winter since the schism caused by Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket, and a number of leading England players were missing. (no New Zealanders were selected). The England captain, Mike Brearley, had had his arm broken during the first part of the winter, in Pakistan, so his vice-captain Geoffrey Boycott, took over. New Zealand’s historic win came in the first Test, at the Basin Reserve. It was an unexpected result in that, in their second innings New Zealand had lost nine wickets for forty-one runs, and England’s target was a modest one. But they were bowled out for sixty-four (Hadlee six for twenty-six: ten for a hundred in the match). Wisden’s match report said that “it would be kind to draw a discreet veil over England’s performance”.

It is hard to blame Boycott. In England’s first innings he had scored seventy-seven. But he took seven hours and twenty-two minutes to do it. His team-mates were becoming increasingly frustrated. In the second Test at Christchurch, which England won (Ian Botham made a hundred in the first innings and took eight wickets in the match) England needed quick runs in the second innings, but the captain seemed to be in his own peculiarly unhelpful “zone”. Derek Randall was controversially run out by the bowler, Chatfield, Botham was sent in to join Boycott, with very clear instructions from vice-captain Bob Willis that were swiftly and ruthlessly followed: “Run the bugger out”.

The New Zealand series began with a high-scoring draw at the Basin Reserve and the players moved on to Christchurch. The game was all over in twelve hours’ play. New Zealand batted first and made 307. The captain took four for 51 but he later described the rest of England’s bowling as “some of the worst” he had seen in Test cricket. Hadlee top-scored with 99. England were then bowled out for 82 and 93, Hadlee taking eight wickets in the match. This was the only time since the nineteenth century that an England side was bowled out twice for less than a hundred in each innings.

England lost the next series, too, in England in 1986. There were two rain-affected draws; New Zealand, led by the astute and engaging Jeremy Coney, won the second Test, at Trent Bridge, by eight wickets. Again the dominant figure was Hadlee. He took ten wickets in the match and scored 68 in New Zealand’s first innings. England had had a dismal time losing five-nil to the West Indies and then losing the series to India in the first part of the summer. It is interesting to read the verdict of Wisden’s editor, Graeme Wright (himself a Kiwi): “I felt by this time England had reached their nadir. New Zealand were a solid side with two outstanding players in Hadlee and Martin Crowe, but I do not think that any England team, possessing pride and spirit, would have allowed themselves to be beaten by them.”

Since 1999 England have generally had the better of things, but. New Zealand are never pushovers. The series against them in 2015 – one-all in a two-match rubber – was infinitely better and more entertaining than the Ashes series of the same year. Now, ridiculously, it is another two-match series and one of those games is a day-night one, where almost anything might happen, especially given England’s extraordinary capacity to be brilliant one moment and rubbish the next.

The sides look quite evenly matched. The home captain Kane Williamson, is up there with Steve Smith, Joe Root, A B de Villiers and Virat Kohli as one of the world’s outstanding batsmen, and the experienced Ross Taylor, if fit, is not far behind. The pace attack, Trent Boult, Tim Southee and Neil Wagner, is highly competitive.

England’s stumbling Ashes campaign has left them with a number of unanswered questions, but at least it looks as if Stokes (born in Christchurch) now that he has been charged with affray, will be available (if he is convicted will they make him captain?).

What is clear is that, as so often before, if England lose to the Kiwis, the knives will be out.

Bill Ricquier

Feature image. By Archives New Zealand from New Zealand (Cricket test at Basin Reserve, 10-15 February 1978) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons