Before the English summer of 1968 the cricket authorities relaxed the applicable rules so that each county could hire an overseas player without having to satisfy residential qualification requirements. Many of the (then) seventeen counties seized the opportunity to hire a big name. Yorkshire of course ignored the relaxation, but Lancashire signed Farokh Engineer, Warwickshire Rohan Kanhai, and Nottinghamshire the biggest prize of all, Gary Sobers.

Hampshire bucked the trend. They went for a 22-year-old South African with no international experience. His name was Barry Richards.

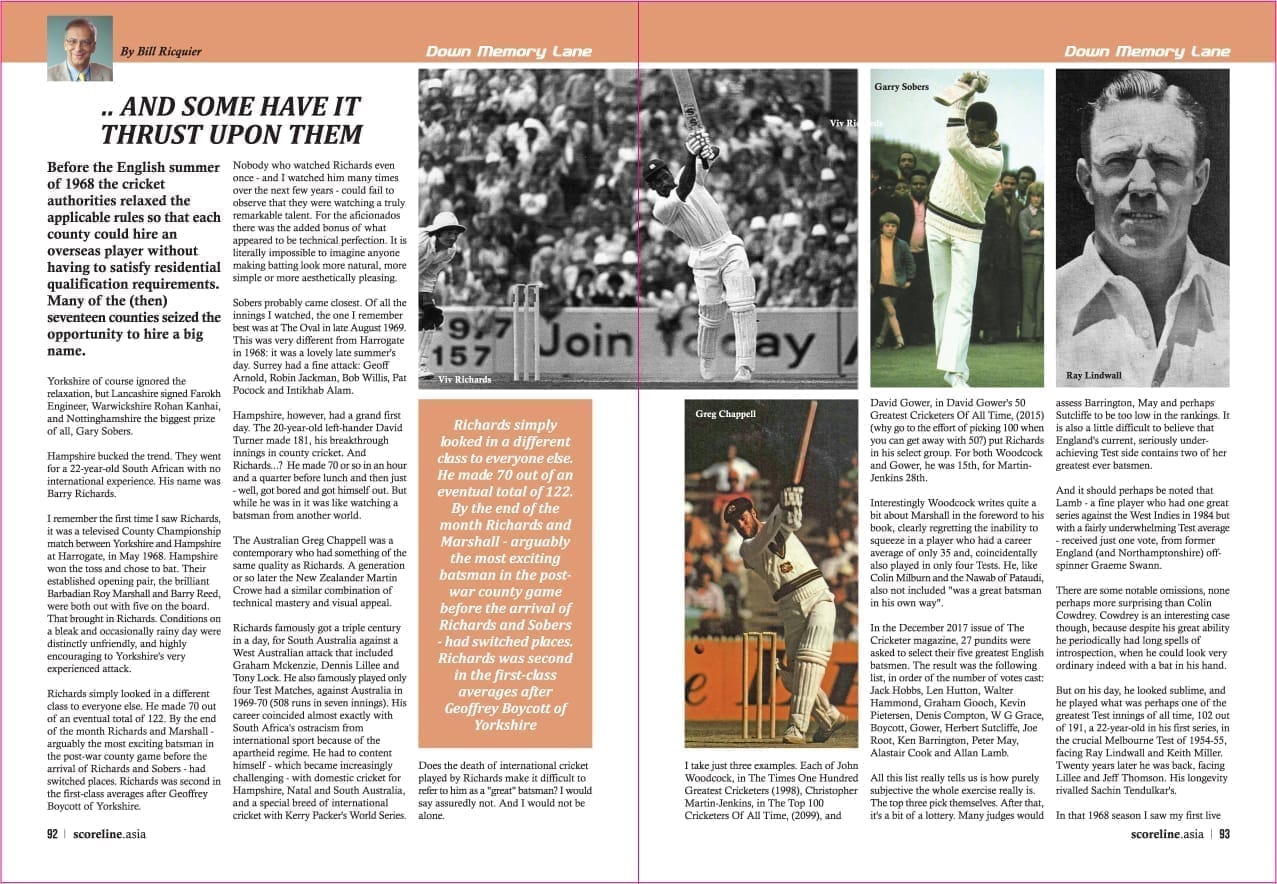

I remember the first time I saw Richards, it was a televised County Championship match between Yorkshire and Hampshire at Harrogate, in May 1968. Hampshire won the toss and chose to bat. Their established opening pair, the brilliant Barbadian Roy Marshall and Barry Reed, were both out with five on the board. That brought in Richards. Conditions on a bleak and occasionally rainy day were distinctly unfriendly, and highly encouraging to Yorkshire’s very experienced attack. Richards simply looked in a different class to everyone else. He made 70 out of an eventual total of 122. By the end of the month Richards and Marshall – arguably the most exciting batsman in the post-war county game before the arrival of Richards and Sobers – had switched places. Richards was second in the first-class averages after Geoffrey Boycott of Yorkshire.

I remember the first time I saw Richards, it was a televised County Championship match between Yorkshire and Hampshire at Harrogate, in May 1968. Hampshire won the toss and chose to bat. Their established opening pair, the brilliant Barbadian Roy Marshall and Barry Reed, were both out with five on the board. That brought in Richards. Conditions on a bleak and occasionally rainy day were distinctly unfriendly, and highly encouraging to Yorkshire’s very experienced attack. Richards simply looked in a different class to everyone else. He made 70 out of an eventual total of 122. By the end of the month Richards and Marshall – arguably the most exciting batsman in the post-war county game before the arrival of Richards and Sobers – had switched places. Richards was second in the first-class averages after Geoffrey Boycott of Yorkshire.

Nobody who watched Richards even once – and I watched him many times over the next few years – could fail to observe that they were watching a truly remarkable talent. For the aficionados there was the added bonus of what appeared to be technical perfection. It is literally impossible to imagine anyone making batting look more natural, more simple or more aesthetically pleasing. Sobers probably came closest. Of all the innings I watched, the one I remember best was at The Oval in late August 1969. This was very different from Harrogate in 1968: it was a lovely late summer’s day. Surrey had a fine attack: Geoff Arnold, Robin Jackman, Bob Willis, Pat Pocock and Intikhab Alam. Hampshire, however, had a grand first day. The 20-year-old left-hander David Turner made 181, his breakthrough innings in county cricket. And Richards…? He made 70 or so in an hour and a quarter before lunch and then just – well, got bored and got himself out. But while he was in it was like watching a batsman from another world.

The Australian Greg Chappell was a contemporary who had something of the same quality as Richards. A generation or so later the New Zealander Martin Crowe had a similar combination of technical mastery and visual appeal.

Richards famously got a triple century in a day, for South Australia against a West Australian attack that included Graham Mckenzie, Dennis Lillee and Tony Lock. He also famously played only four Test Matches, against Australia in 1969-70 (508 runs in seven innings). His career coincided almost exactly with South Africa’s ostracism from international sport because of the apartheid regime. He had to content himself – which became increasingly challenging – with domestic cricket for Hampshire, Natal and South Australia, and a special breed of international cricket with Kerry Packer’s World series.

Does the death of international cricket played by Richards make it difficult to refer to him as a “great” batsman? I would say assuredly not. And I would not be alone.

I take just three examples. Each of John Woodcock, in The Times One Hundred Greatest Cricketers (1998), Christopher Martin-Jenkins, in The Top 100 Cricketers of All Time, (2009), and David Gower, in David Gower’s 50 Greatest Cricketers Of All Time, (2015) (why go to the effort of picking 100 when you can get away with 50?) put Richards in his select group. For both Woodcock and Gower, he was 15th, for Martin-Jenkins 28th.

Interestingly Woodcock writes quite a bit about Marshall in the foreword to his book, clearly regretting the inability to squeeze in a player who had a career average of only 35 and, coincidentally also played in only four Tests. He, like Colin Milburn and the Nawab of Pataudi, also not included “was a great batsman in his own way”.

In the December 2017 issue of The Cricketer magazine, 27 pundits were asked to select their five greatest English batsmen. The result was the following list, in order of the number of votes cast: Jack Hobbs, Len Hutton, Walter Hammond, Graham Gooch, Kevin Pietersen, Denis Compton, W G Grace, Boycott, Gower, Herbert Sutcliffe, Joe Root, Ken Barrington, Peter May, Alastair Cook and Allan Lamb.

All this list really tells us is how purely subjective the whole exercise really is. The top three pick themselves. After that, it’s a bit of a lottery. Many judges would assess Barrington, May and perhaps Sutcliffe to be too low in the rankings. It is also a little difficult to believe that England’s current, seriously under-achieving Test side contains two of her greatest ever batsmen. And it should perhaps be noted that Lamb – a fine player who had one great series against the West Indies in 1984 but with a fairly underwhelming Test average – received just one vote, from former England (and Northamptonshire) off-spinner Graeme Swann.

There are some notable omissions, none perhaps more surprising than Colin Cowdrey. Cowdrey is an interesting case though, because despite his great ability he periodically had long spells of introspection, when he could look very ordinary indeed with a bat in his hand. But on his day, he looked sublime, and he played what was perhaps one of the greatest Test innings of all time, 102 out of 191, a 22-year-old in his first series, in the crucial Melbourne Test of 1954-55, facing Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller. Twenty years later he was back, facing Lillee and Jeff Thomson. His longevity rivalled Sachin Tendulkar’s.

In that 1968 season I saw my first live day of Ashes cricket, the fourth day of the third Test at Edgbaston. In the afternoon there was a brief but sublime innings of 39 not out from Tom Graveney, who seemed to have two, if not three separate England careers, the last of which was easily the best. He is one of those classic uncertain cases where it is difficult to be sure whether he was a great player or not.

How important are averages in assessing whether a player is great or not? Well they must mean something; runs, after all, are the only currency batsmen operate in. Forty-plus was always thought to be the minimum for a top player. That may have gone up a bit in recent years as batting averages generally have escalated. Javed Miandad, an undoubtedly great player, had an average of well above 40 from the very beginning of his career. Someone like Gooch struggled to begin with and only really came good in international cricket in the second half of his career. Going back to the Cricketer list, Don Bradman famously has the highest Test batting average of all but of those who have scored 4,000 Test runs or more, Sutcliffe has the third highest and Barrington the fourth.

Aesthetics obviously has something to do with deciding whether a batsman is great. Gower was wonderful to watch but was he really a greater player than that other English left-hander John Edrich? Gower averaged 44, Edrich 43. Both had superb records against Australia. But Gower looked nicer. Edrich was one of those nuggety, rock-like players who just get in and stay in, exemplified most successfully by Allan Border and currently by Dean Elgar.

Two things single out the great from the very good. One is obvious really. They just do things that ordinary players can’t do; look at Brian Lara. The second, related thing is the way they impose their personality and their presence on the occasion. The classic exemplar of this was the other great Richards, the Antiguan Vivian whose swaggering walk to the wicket could itself be sufficient to intimidate the opposition. Pietersen – one of the greatest batsmen of the 21st century – is another. But it is not just batsmen like them. The great accumulators – Boycott, Cook, Sunil Gavaskar, Hanif Mohammed – are just as adept at dominating a contest in their own way.

Is our conception of what constitutes a great batsman going to change, given the way the game itself is changing? Who is the greatest batsman in the current England side? Is it Root? or is it Jos Buttler?

This may seem absurd, but is it, really? Buttler is a supremely gifted athlete and generally recognised as the most dangerous batsman in the world in white ball cricket. His batsmanship is inventive – genuinely so, like K S Ranjitsinhji and Tillakaratne Dilshan, but, like all the great players, the fundamentals are strong. Buttler is no slogger. The best comparison is with that other brilliant athlete and part-time wicketkeeper, A B de Villiers.

Although he was quoted early in 2018 casting doubt on the longevity of Test cricket, he did not, like Alex Hales and Adil Rashid, turn his back on the longer format. That was shrewd, because no sooner was he back from a triumphant campaign in the Indian Premier League than he was playing for England in the first Test against Pakistan at Lord’s.

Buttler was a revelation in that (too brief) series. In his previous Tests he had shone fitfully but, as a batsman he had never seemed entirely sure of his role. Now he seemed absolutely certain, and by some distance the most assured batsman in the side. It will be fascinating to see how he does in the series against India that is about to start. it is not easy to make an impact from number seven in the order (Wasim Raja made over 500 runs from there for Pakistan against the West Indies in the Caribbean in 1976-77) but Buttler has the skill and the temperament to do it.

For the truly gifted the challenge is always to – well, make sure there is a challenge. As almost all the cricket Buttler plays is international cricket, in one form or another, that should not be a problem. But it was the defining tragedy – if that’s not too strong a word – of Richards’ career. Watching him – as I did in 1970 – on the proverbial grey morning in Derby, I was reminded of something Neville Cardus said about Hammond.

“Hammond in his pomp occasionally suggested that he was batting lazily, with not all his mind alert. When he at times scored slowly on a perfect wicket he conveyed to us the impression that he was missing opportunities to get runs because of some absence of mind or indolence of disposition. He once said to me after he had made a large score on a comfortable wicket, “It’s too easy.””

Bill Ricquier