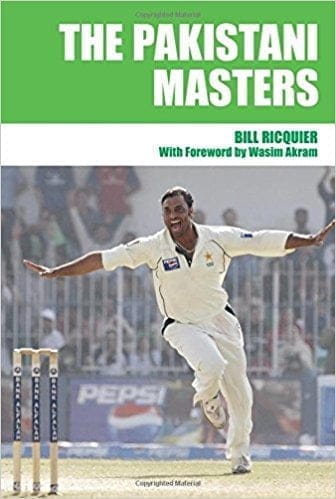

This article first appeared in my book, The Pakistani Masters. It has been updated following Imran’s success in the general election in July 2018, which left the PTI as the largest political party and Imran set to become his country’s next leader, in only the second transition from one civilian government to another in Pakistan’s history. This is part two of three.

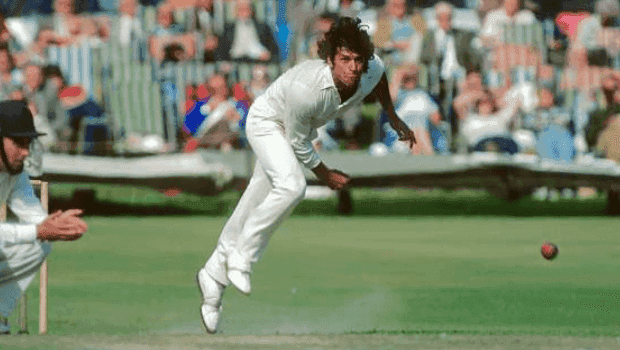

Aged 29 when he joined his team for the tour of England in 1982, having spent the first part of the summer with Sussex, Imran Khan was – apparently – at the height of his powers as a cricketer. As a bowler, he had reached the stage where genuine pace was allied to a range of skills of the highest quality. He had always possessed the ability to swing the ball into the right-hander: even in his rather embarrassing Test debut eleven years earlier he had at least been able to do that. But at that point, it came out at a pace a little above medium and he had no means of controlling or utilising the swing or of varying either pace or movement. Over the years, he grew and he worked and he studied and he learned. He was always happy to talk cricket and to digest help and he always acknowledged help, which sometimes came from improbable sources, John Parker, the New Zealand batsman who played for Worcestershire suggested a changes to his action which seemed to work – a little jump which later developed into a leap as he went into his delivery stride. Invaluable encouragement and advice regarding his run up and getting more side-on and closer to the stumps came from Mike Procter and John Snow, team-mates at World Series Cricket: that aided the development of an outswinger. But perhaps the greatest assistance came from his Pakistani team-mate Sarfraz Nawaz.

From early days, Imran found it relatively easy to obtain movement in the air and off the pitch in English conditions, at least with the new ball, but in Faisalabad and Lahore, – less so in Karachi, where there was often some humidity – it was a different story.

Sarfraz imparted the advantages of shining one side of the ball so that even an old ball would swing. As early as 1976-77 in Australia Ray Robinson was commenting on what an indefatigable shiner of the ball Imran was. It meant that even in the most apparently unhelpful conditions – and many a fast bowler has found conditions in Pakistan exceptionally unhelpful – Imran could conjure up remarkable movement. If one side of the ball were soaked with sweat, and consequently heavier things got even more interesting. Together, Sarfraz and Imran pioneered the phenomenon of “reverse” swing.

He was certainly among the most feared fast bowlers of his generation. Six feet tall and perfectly designed for the job, his strict regime that eschewed alcohol and tobacco gave him terrific stamina to go with pace, guile and technique. While the outswinger came and went the inswinger was an ever-present and often vicious threat, whether directed at the toes, the stumps, the rib-cage or the helmet.

Imran, in Test matches and particularly as he got older, batted classically, in the grand manner, and rarely gave vent to flamboyant displays in the manner of Botham, or Kapil Deve or Wasim Akram. But that was because being captain of Pakistan was a serious business and if runs were needed from him, it probably meant his team were in trouble. As a youngster, he taught himself to hook, realising he would be on the receiving end of many a retaliatory bouncer. It was always a high-risk shot, though, and after getting himself out at a most critical moment in the Edgbaston Test in 1982, he avoided it. In county cricket, he was more of a dasher and had plenty of runs to show for it. On four occasions, he made over a thousand runs in a season. There too the demeanour was magisterial, although Barclay said he was invariably nervous and restless before batting.

The question was, as it always is in these situations, how would the captaincy affect his performance as a player? It was a question that had recently been asked regarding Botham, and answered in the remarkable Ashes series of 1981. Imran was older and more mature when the captaincy of Pakistan came to him. And of course, it transpired that it was a crown he had been born to wear.

Imran had four principal ambitions as captain: to beat England, because of the colonial past and the tone of condescension that, still dominated relations between the two countries; to beat the West Indies, because they were the best; to beat India, especially in India, because they were India; and to win the World Cup. Everything else was secondary. Imran always enjoyed playing in Australia – he was to spend a season with New South Wales – and there were defeats to be avenged, but as a cricketing power Australia were in decline. New Zealand sometimes appeared to be beyond Imran’s radar screen; he had same slip-ups against Sri Lanka, again not always highly regarded.

* * * * * * * * * *

The first challenge was England in 1982. England – without their South African rebels – won the one-day series with some ease. They also won the first Test at Edgbaston by 113 runs but the game was closer than the result suggests. Bob Willis won the toss but most of the English batsmen struggled against Imran, who took seven for 52, and the leg-spinner Abdul Qadir. Whenever the England batsmen seemed on the verge of dominance. Imran would bring himself back on and force a breakthrough. They finished with 272. A number of Pakistan’s batsmen got going but too many were out to brainless shots, Imran included; they made 251. Derek Randall’s “lucky” century (Imran) enabled England to set a target of 313. Pakistan subsided for 198. Imran, man of the match, made batting look relatively easy in his 65.

Pakistan won a historic victory in the second Test at Lord’s, only their second in England. The individual honours went to Mohsin Khan, who scored a double century in Pakistan’s first innings, and to his fellow opening batsman Mudassar Nazar, who rather improbably took six for 32 in England’s second innings. But Imran was no less central a figure. His bowling was important. He troubled David Gower and Allan Lamb in England’s middle order. He gave the first Sunday of Test cricket at Lord’s a dramatic start by having England’s last man Robin Jackman leg before with the score on 227; the follow-on target was 229. But his captaincy was crucial. Until this game nobody was quite sure what sort of a captain he was going to be. By the end of it, nobody had any doubt: his forceful personality was evident in every move. If Gary Sobers was Imran’s hero as a player, the captain he regarded most highly was Australia’s Ian Chappell. In his early days as a Pakistan cricketer, Imran had seen too much negative captaincy. He was proactive, rather than reactive; he led from the front and he had the respect of his players.

The two sides went to Headingley all square. The game was dramatic and exciting, England winning by three wickets. Pakistan won the toss and batted, making 275, Imran top-scoring with 67 not out, which included two sixes and nine fours. England made 256: Imran took five for 49 in 25 overs. In a particularly testing spell after lunch on the second day he dismissed Mike Gatting, Lamb and Chris Tavare in nine balls.

There followed a poor batting performance from Pakistan against Willis and Botham. Miandad played well for 52 but the other recognised batsmen failed until Imran came in at 106 for 5. To begin with he was all studious defence but gradually moved to carefully – judged aggression, assisted by an adhesive tail Sikander Bakht hung around for over an hour for 7 before being adjudged caught at short leg by Gatting off Via Marks: the score was 199 for nine. Imran holed out in the next over.

England needed 219 for victory with the better part of two days left. They seemed to have the game sewn up when debutant Graeme Fowler and Gatting took the score to 168 for one but Imran and Mudassar, swinging the old ball extravagantly, reduced them to 199 for six and had play carried on that day Pakistan would very likely have won. But the batsmen accepted an offer to go off for bad light and victory for England the next day proved to be a formality.

It was a series that Pakistan should probably have won. They had been unlucky with injuries, Sarfraz and Tahir Naggash missing the final Test. Certainly, it was hard not to think that Imran did not deserve to be on the losing side. His discipline, his effort, his aggression as a bowler and his leadership in the field were exemplary. But at this stage, he could not quite get everyone to follow that example. Imran himself conceded that it was undisciplined batting which cost Pakistan the series: he felt they should have won at Edgbaston, let alone Headingley.

And then there was the umpiring, Imran and the manager, Intikhab, had complained about the umpiring at Edgbaston, and the issue became something of a running sore. Commentators at the time suggested that both sides had cause to grumble when it came to poor decisions. The focal point of Pakistan’s unhappiness came in the third Test – where everybody seemed to agree they got the rough end of the stick – when one of the officials was the experienced and respected David Constant. The Indians, who had toured in the earlier part of the summer, had objected to Constant’s standing in the Tests because they felt unfairly treated when play had started in a one-day international at Headingley before – they maintained – the pitch had had a chance to recover from the effects of an overnight storm: India lost heavily. The incident was reminiscent of Pakistan’s Test at Lord’s in 1974 when they had had to face Derek Underwood on a pitch which the covers had failed to protect from overnight rain: Constant had been one of the umpire’s in charge then too. The bone of contentions at Headingley was the dismissal of Sikander in Pakistan’s second innings, Imran said the decision was “truly bizarre”. Even the judicious Christopher Martin-Jenkins suggested England’s appeal had been lodged more in hope than expectation. Not that it would have been the first optimistic appeal of the series. While everyone admired Pakistan’s cricket under Imran, one common criticism was the apparently orchestrated appealing, especially when Qadir was bowling. As the umpires, according to Imran, had no more idea than the batsmen of what the ball was going to do, the batsmen usually got the benefit of the doubt.

The sense of grievance carried over to Pakistan’s next tour of England, in 1987. The genial and popular Intikhab was replaced as manager by the loquacious and combustible Haseeb Ahsan. This was very good for Imran: they made a perfect “good cop, bad cop” combination. Haseeb could do all the talking and take the flak when people complained about those Pakistanis stirring it again. Imran could look the part and carry on doing what he did best, inspiring his cricket team to victory.

Imran was 34 by now, and troubled by a stomach muscle injury at the start of the tour. This was Pakistan’s first full, five-Test tour of England since 1962. England had returned from their Ashes victory in 1986-87 and were full of confidence under Gatting. The first two Tests were rain-affected draws. The final Test at The Oval saw a run-glut in which Miandad made 260 and Saleem Malik and Imran made hundreds. The fourth, at Edgbaston looked certain to be a draw after each side made a substantial first innings score, but Pakistan in their second innings collapsed against Neil Foster, Imran holding firm for two hours to make 37, England required 124 from eighteen overs. Imran and Wasim Akram bowled through to keep them to 109 for seven.

The only game to reach a positive result was the third Test at Headingley. Imran, fully fit at last, took charge of the game on the first day and Pakistan never let go. Gatting opted to bat on a fine day with high cloud but before long England were struggling at to 31 for five. In his first spell, Imran took three for 16 in seven overs. He and Wasim, bowled at a torrid pace and extracted extravagant swing. It transpired that the pitch also had uncertain bounce. So conditions certainly helped the pace bowlers but Imran and Wasim exploited them perfectly. England were all out for 136. They only managed to take two wickets by the close of the first day. Foster in particular bowled well but Pakistan fought hard to make 353. When England batted again, Chris Broad and Tim Robinson were out in Imran’s first two overs. Television replays, mercilessly repeated at the ground, suggested that Broad had been unlucky to have been adjudged by umpire David Shepherd, to have been caught behind. Further controversy erupted when wicket-keeper Salim Yousuf claimed to have caught Botham off a ball which he appeared to have caught, dropped and caught again: Imran was swift to reprimand Yousuf. Yousuf had not been alone in appealing and it was the sort of incident which put Pakistan’s complaints about the umpiring – and Imran’s attempts to claim the moral high ground – in perspective. Anyway, Pakistan were rampant. England were all out for 199 on the fourth morning: Imran had taken seven for 40, which included his 300th Test wicket.

At the end of the tour, Gatting said he thought England had won the series on points, a laughable comment really. The two series, 1982 and 1987, said a lot about Imran, his captaincy and his relationship with England. In 1982, he was at the start of his reign. But he lost little time in stamping his authority on the side. Almost his first action was to drop the senior player, his cousin, Majid Khan. That was always the way with Imran. He had seen so many captains before him have problems with selection. He always wanted his team and he usually got it. One saw this with his backing of Wasim and, later, Waqar Younis. By the final Test of 1987, many of the senior players though that Qadir was out of form and should be dropped: Imran did not agree, and insisted on picking him. Qadir took seven for 96 in England’s first innings.

One of the things that Imran was anxious to change was the subservience traditionally shown by Pakistani cricketers to English cricket officials. He had found this irritating even on the 1971 tour when he was an inexperienced 18-year old. This was part of the reason for the business regarding Constant, but it went deeper than that. Today, it is perhaps easier to appreciate his frustrations because today there is at least a slightly greater appreciation in cricketing circles of the gulf in culture between England and Pakistan. Back then there was simply incomprehension, certainly on the English side. Martin-Jenkins made an unwittingly droll comment symbolising this in a report on the 1982 Edgbaston Test. England had had a good final session on the Friday: “The cheese and wine at Bernard Thomas’s garden party on Friday night slipped down English throats more easily. Pakistan had let a good chance slip.” Let’s hope Bernard had ordered some chapatis.

If Imran had had a complaint about Bernard’s party, other than the wine, and possibly the cheese, it would probably have been that the guest list was not grand enough, unless Emma Sergeant or – heaven forbid – Jeffrey Archer, had strolled in. Of course in 1982, Imran’s social horizons had not reached the stratospheric levels they were to attain in later years. But as an Oxford – educated scion of Lahore’s upper echelons, blessed by almost indecent good looks, he had a lifestyle that was considerably more exotic and exalted than that of the average county professional. With a base in South Kensington – where else? – as well as Lahore it seemed as though he had a foot in both camps. He was too shrewd to follow in the footsteps of Paul Scott’s Hri Kumar, in The Raj Quartet: too English for the Indians and too Indian for the English. And he was too proud. Imran liked the cosmopolitan feel of London; but the Punjab was home.

And he spent many enjoyable and successful years as a professional cricketer in England. He was a popular figure at Sussex and got on well with the old Etonian skipper, Barclay. His increasingly patrician air and rather haughty demeanour undoubtedly rubbed some people up the wrong way; his slightly drawling voice, instantly recognizable became the subject of continued mimicry by the slightly tiresome Dermot Reeve. But Ivo Tennant’s biography mentions only one English cricketer whom Imran actually disliked: surprisingly Hampshire’s dashing leader, Mark Nicholas. Outside the tiny and inward – looking cricket community, the English admired his aquiline features and rippling torso and wondered, vaguely, where they had seen them before. Then they remembered: the Greek Antiquities Department at the British Museum. That was the men; the women just fell in love with him.

Imran featured prominently in two of the great dramas that have periodically convulsed cricketing relations between England and Pakistan. The first was umpiring. The disgruntlement over David Constant has been mentioned. Pakistan wanted both him and Ken Palmer withdrawn from the panel for the 1987 series but the Test and County Cricket Board refused and their attitude irritated Imran. He sometimes got carried away, as at The Oval in 1987 when he Mudassar openly fulminated against Constant when he turned down an appeal against Botham.

But it would be wrong to regard this as an anti-English campaign: indeed, Imran conceded that English umpires were the most professional in the world. He criticised umpires wherever he went. Pakistan would have beaten New Zealand in Auckland in 1978-79 but for some “dubious umpiring decisions”. In Sri Lanka, in 1985-86 the Pakistanis discovered that “biased umpiring was part of a plan”. Umpiring mistakes in the closing stages of the third Test in the Caribbean in 1987-88 contrasted so starkly with the generally high standard encountered earlier that he could only conclude that “patriotism had taken over”. And then, of course, there was Pakistan. Imran missed the series between Pakistan and England in 1987-88 which was memorable – notorious would perhaps be better – for the appalling confrontation between Gatting and the umpire Shakoor Rana that somehow encapsulated English grievances about umpiring on the sub-continent. Whatever the rights and winnings of the Faisalabad incident, this was the sort of attitude Imran found frustrating. When David Constant made a mistake, it was one of the best umpires in the world (because he was English) making a rare, if human error; when Shakoor Rana did, it was another “Paki cheat”. Imran felt that the standards of umpiring in Pakistan were getting better – a comment that seems almost laughable given that it was written after the England tour of 1987-88 when there were real problems with Shaheel Khan and Shakoor Rana. Imran’s point was wherever the game was played, visiting teams operated at a potential disadvantage. Talking of patriotism, though, there is a wonderful picture in Scyld Berry’s book about England’s 1987-88 tour of Pakistan of Shakoor Rana proudly wearing Mudassar’s Pakistan cap while umpiring a Test. Imran first advocated neutral umpires as long ago as 1978.

The second controversy, not unrelated, was ball-tampering. Allegations thereof became something of a Pakistani speciality. There were quite a few formidable swing bowlers around in the 1980s and 1990s: Dennis Lillee, Kapil Dev, Ian Botham, Terry Alderman, Bruce Reid. But see Imran Khan, Wasim Akram or Waqar Younis unleashed and there seemed to be something fishy going on. Complaints only started to be made once Pakistan began winning; in 1982 it was suggested after their victory at Lord’s that their bowlers had used some kind of illegal polish to make the ball swing more.

Imran was indignant. Similar sorts of allegations were made after the Headingley victory in 1987. Tongues really started wagging in the early 1990s and reached a crescendo during Pakistan’s tour of England in 1992. Imran had retired by this time but he added his own not inconsiderable shovel of fuel to the flames in 1994 by admitting that he had once – and once only – used a bottle top to “rough up” a ball in a county match back in 1981.

Imran was always stout in his defence of Wasim and Waqar. His main points were that when they played in England, balls they used were regularly inspected by the umpires and that, almost parenthetically, “interfering with” the ball, in the widest sense was a tradition in English cricket almost as hallowed as the tea interval. It was this second general assertion, no doubt casually uttered to a journalist, that brought Imran nose to nose, as it were, with Botham in the High Court in London in 1996: Botham (and Lamb) sued for defamation because, he claimed, Imran had accused him of ball-tampering and of being ill-educated and “low-class”. Similar comments were made in Ivo Tennant’s biography of Imran; after its publication Imran wrote a curious letter to Botham, saying that he thought Botham was a worthy opponent and an outstanding sportsman and that he just wanted to “put the record straight”. The jury found in favour of Imran. If the case established anything at all it was that Imran’s point about interfering with the ball being widespread in English cricket was not without merit (he had not suggested in the original article that Botham had interfered with a cricket ball; the issue was raised by way of a defence of justification brought up at the that moment and subsequently withdrawn). There was much inconclusive discussion about where to draw the line between accepted custom, sharp practice and downright illegality. Incidentally, Botham in his autobiography leave no room for doubt regarding his views about the methods sometimes employed by Pakistan’s pace bowlers.

The end result surprised many observers. Imran had, after all, apologised to Botham for alleging, in his plea of justification, that Botham had interfered with the ball in Test matches against India and Pakistan in 1982. Had it been a cricket match, the trial would probably have been a draw.

The case showed what an enigmatic relationship Imran had with the English. He was never going to be as popular as Botham, an authentic English hero. But he had a touch of “celebrity” glamour, enhanced by his marriage – subsequently dissolved – to the fragrant, and fabulously wealthy, Jemima Goldsmith that even Botham could hardly match. At the same time, he was a citizen of what was to all intents and purposes an Islamic state and a friend of one of its most disagreeable leaders, the genuinely despotic General Zia-ul-haq.

All that now seems a very long time ago. Imran has withdrawn more or less completely from British life. In 1996 he founded his own party, Pakistan Tehrerk-e-Insaf (PTI). In March 2006 he earned what must have been regarded as a signal a badge of honour by many people, being detained in his home in Islamabad during the visit to Pakistan of President George W. Bush. And he gradually became more immersed in national politics.