There could be no doubt as to which was the outstanding men’s international cricket team in the calendar year 2022. England won nine Tests out of ten between June and December, and in November they won the World T20 Championship in style, becoming the first side to hold the 20-over and 50-over trophies simultaneously. Their chances of adding the World Test Championship to the trophy cabinet seem remote, as they are currently ranked fourth behind Australia, India and Sri Lanka. This is partly, but only partly, a result of the quirks of the system. It is also a result of the fact that England play more than anyone else and, until June, were not playing very well. They had won just one of their last seventeen Tests.

The year started with England’s pitiful 4-0 defeat in The Ashes.

It was not apparent at the time but the seeds of England’s dramatic recovery were actually sown in their first Test of the year, the fourth of the series, at Sydney. This was the one game of the series that England contrived not to lose. There was a dramatic finale, with last pair Stuart Broad and James Anderson hanging on for a draw; England finished 115 behind, so we were not exactly in breathless hush territory.

The reason England managed not to lose was that one of their middle order batsmen made their only century of the series in their first innings. This was Jonny Bairstow, who had been picked for only one of the first three Tests. Joining Ben Stokes with the score 56 for four in response to Australia’s 416 for eight, Bairstow played a pugnacious, counter-attacking innings of 113; he also made 41 in the second innings. He missed the final humiliation at Hobart through injury.

England’s woes were not yet over. In March they lost a depressing three-Test series in the Caribbean one-nil – Bairstow made 140 in the first Test at North Sound.

By the beginning of the English summer the managing director of England men’s – cricket, Ashley Giles and the coach, Chris Silverwood, had left their posts, as had red ball captain Joe Root.

Someone at or connected with the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB) then made an unusually brilliant decision – the appointment of former Kent and England batsman and popular Sky pundit Rob Key as managing director of England men’s cricket. For it was Key who appointed first Stokes as Test captain – probably inevitably – and then, totally unexpectedly, Brendon McCullum as Test coach. Matthew Mott, who had built up a formidable reputation as coach of Australia’s all-conquering women, was appointed white ball coach.

The difference this has made to England’s Test cricket has been little short of bewildering, and, few could disagree, utterly wonderful.

The transformation was certainly quick and apparently seamless but not immediately apparent. England were to play ten further Tests in 2022 – three against New Zealand, South Africa and Pakistan, and one against India, winning nine and losing one (the first Test against South Africa). The series against South Africa was a strange affair and slightly different from the rest. What the other seven games had in common was that although the bare facts suggest that England won reasonably comfortably in the end they were all, without exception, games which, at some point, sometimes more than once, that England might lose. But they didn’t. And in each of those nine games, England’s bowling attack, generally respected, if only because of its antiquity, but hardly feared, took 20 wickets.

The first Test against New Zealand at Lord’s was an intriguing game which England wrapped up by five wickets on the fourth morning. Seventeen wickets had fallen on the first day so the game never seemed likely to go the distance. England’s target was 276 and when Stokes was apparently bowled by Colin de Grandhomme for one the game seemed up. But it was a no ball and Stokes made a crucial 54. The match winner though was Root who made a sublimely constructed and paced century. It was a memorable win but apparently – apart from Stokes’ own relentlessly aggressive approach with the bat – conventional Test cricket. Incidentally Bairstow failed in both innings. He had literally just arrived back from the Indian Premier League (IPL) and he had not played a first-class game since the third Test against the West Indies, and there was some talk that his place should have gone to the promising fellow Yorkshireman Harry Brook.

The second Test, at Trent Bridge, was something else. The scorecard really does tell the story. New Zealand batted first and made 553. In their second innings they made 284. That’s 837 in the match. But England won by five wickets on the fifth evening. Bairstow, who was joined by Stokes with the score on 92 scored 136 off 92 balls, with fourteen fours and seven sixes. Stokes made 75 not out with ten fours and four sixes. The run rate for the innings was an astounding 5.98.That doesn’t happen in Test cricket; it just doesn’t.

In the third Test, at Headingley, New Zealand must have thought “Aha! Got’em!”. Facing the visitors’ 325, England were reeling at 55 for six. Bairstow was joined by debutant Jamie Overtonand the pair put on a record 241 for the seventh wicket (Bairstow 162 off 157 balls, with 24 fours, Overton 97). (Bairstow also holds England’s sixth wicket partnership record of 399 with Stokes against South Africa at Cape Town in 2015-16; Len Hutton and Colin Cowdrey are the only other England players to hold two partnership records.) England won the match by seven wickets. Bairstow made 71 off 44 balls in the second innings, with eight fours and three sixes. England chased down 296 at a run rate of 5.44.

Next came the rescheduled fifth Test from the 2021 series against India. This was another extraordinary game. India batted first and made 418, with a boisterous century for Risharbh Pant (strike rate 131) and another for Ravindra Jadeja. The innings concluded with Jasprit Bumrah taking 35 off an over from Broad. Anderson took five for 60 off 21.5 overs.. England replied with 284, Bairstow making a relatively restrained 106 off 140 balls; many judges regarded it as his best innings of the season. India were then bowled out for 245 (Stokes four for 33) leaving England a target of 378. Again, history would suggest that this was, to say the least, very challenging. But Stokes and McCullum appear not to know or care about cricket history. The openers got the innings off to a flyer and the ease with which the fourth wicket pair of Root and Bairstow, went about their business made the target seem almost risibly straightforward. Both made not out hundreds; for Root it was his fourth Test-hundred of 2022, and for Bairstow his sixth, to add to the six he had made in his previous 78 Tests.

Now it was the turn of South Africa, then second in the ICC World Test Championship. ”Bazball” won’t work so well against them, sceptics muttered. England neglected to turn up for the first Test, at Lord’s, which the visitors won by an innings despite making only 326 themselves (they have failed to reach 200 in eight Test innings since).

England returned the compliment in the second Test at Old Trafford, winning by an innings and 85 runs. South Africa’s batsmen floundered in both innings – nobody managed 50 in either innings. The two Bens, Stokes and Foakes, made hundreds for England. Bairstow, in his last Test before suffering a serious knee injury, made 49. England demolished South Africa in just over two days’ play at The Oval.

Well, it won’t work in Pakistan, they said. Right. Stokes’ team became the first in history to win a three-Test series in Pakistan 3-0.

There seemed to be problems when in the run-up to the first Test at Rawalpindi fourteen of the England squad fell sick. In the event only Foakes of the chosen eleven missed the match. The first day was sensational. England closed, after only 75 overs, on 506 for four. To students of Test cricket this literally beggars belief. They finished with 657 at a run rate of 6.50, by some distance the highest run rate attained in any completed innings in Test cricket. Four batsmen made centuries, Brook in his second Test, top scoring with 153. Pakistan responded with 579 at a more conventional rate of 3-72. That is not slow – the last thing Stokes wanted to do was slow the game down. Debutant Will Jacks took six for 161 in 40.3 overs. In their second innings England scored even faster, at 7.36 an over, with Brook hitting 87 off 65 balls, including 24 in an over, an England record. Stokes’ declaration set Pakistan 343 to win – gettable in those conditions. Stokes’ handling of his resources was masterful. The tension was palpable as the shadows lengthened and dusk fell. England won by 74 runs. The extraordinary Anderson took four for 36 in 24 overs.

It would be an over-simplification to say that the other two games followed a similar pattern but there is an element of truth in it. Both games, like Rawalpindi, and very unlike many games one could think of in Pakistan – one has only to think of the series against Australia earlier in the year or the current one against New Zealand – utterly riveting from beginning to end. Brook scored a century in each and at Multan in the second Test broke his own record by scoring 27 off an over. What the two games had in common was that it really did look at one stage that England were going to lose. Stokes’ declaration at Multan was brilliant. It was deliberately designed to make Pakistan think they could win, but Babar Azam and his men could not quite work out how to react. In the end the margin was only 26 runs. There it was the pace men, especially the tireless Mark Wood, who did most of the damage. In Karachi, where Pakistan batted first, it was mostly the spinners.

One final point about Multan. England batted first and made 281 off 51.4 overs (opener Ben Duckett – yes, opener, 63 off 49 balls). The run rate for the whole innings was 5.43. That is the third highest run rate for the first innings of a match in Test history. The highest of course is England’s 6.50 at Rawalpindi. The second highest was attained by New Zealand against Australia at Christchurch in 2015-16. They made 370 at a rate of 5.63, and their captain made 145 off 79 balls. That was Brendon McCullum, in his final Test appearance. (Australia won the match.)

It is easy to see what Stokes brings to the equation. He leads from the front as a player. He is tactically astute and inventive, and a brilliant man-manager. McCullum’s contribution is more nebulous but no less significant. He has given the players the licence and the confidence to play the way they are playing, and more or less ordered them to enjoy it, to go back to the days when, for them, with their siblings and their mates, cricket was, well, just a game. The contrast between England before and after McCullum, a matter of weeks, is startling.

Will it make a difference to the way Test cricket is played generally? Not necessarily. Australia and India will feel that they have nothing to learn from England about how to win Test matches. The West Indies captain, Kraigg Braithwaite, asked if he thought “Bazball” would spread across the cricketing world, said that the concept was fine but that you had to have the right players. All that said, the 2023 Ashes should be a thriller.

There was, as always, some enthralling Test cricket across the cricketing world, but also genuine cause for concern.

A major issue is the growing proliferation of the two-Test series. It is very difficult to get really interested in a two-Test series. (It is absurd that England are only playing two Tests in New Zealand in February 2023.) It suggests that the cricket authorities are happy to let Test cricket wither away apart from the “marquee” series such as The Ashes and India v Australia (another mouth-watering prospect for early 2023).

Australia are firmly on top of the World Test Championship. They once again seem invincible at home, their pace arrack plus Nathan Lyon a match for any opposition. Marnus Labushagne remains the world’s top batsman, while Steve Smith is returning to form. David Warner struggled for much of the year but made a typically punchy double century in his hundredth Test, against South Africa at the MCG.

India had a relatively quiet year, winning series against Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. Had they lost the second Test to Bangladesh, which at one point seemed likely, that would have had implications for the World Test Championship, but they look like a shoo-in. India watchers will be concerned about the serious injuries suffered by Pant in a road accident on 30 December.

The reigning World Test champions, New Zealand, had an underwhelming year. Kane Williamson, 32, stood down as Test captain and was replaced by Tim Southee, 34. Williamson made a masterly double century against Pakistan in Karachi at the end of the year.

The return of the “big guns”, Australia and England, to play in Pakistan was a genuine cause for celebration. The home side lost both series, but Babar enhanced his reputation as one of the world’s top batsmen, and in the Multan Test against England, debutant leg-spinner Abrar Ahmed took eleven wickets.

It seems incredible now but for a while South Africa headed the World Test Championship table; they have only just slipped below England. Their pace attack is world class; their batting – Dean Elgar and Tembo Bavuma – one century in 52 Tests – apart, is barely county standard.

For West Indies it was what has sadly become the same old story. They could hold their own at home – in empty grounds, unless England were playing – but were generally a lost cause away. Braithwaite ploughed a lone furrow with the bat, but in Australia Tagenarine Chanderpaul – a chip off the old block if ever there was one – showed real potential.

What was the most heartening Test victory of the year. I would vote for Sri Lanka’s victory over Australia in the second Test at Galle. Australia had overwhelmed the hosts by an innings at the same venue in the first Test. In the second game Sri Lanka won by an innings and 39 runs. Left-arm spinner Prabath Jayasuriya took 12 wickets in the match; he has taken 29 in the three Tests he has played. And Dinesh Chandimal achieved something that none of the great Sri Lankan batsmen who came before him had done: he made a double century against Australia. But this was not all. The victory came against the backdrop of civil unrest – there were demonstrations in Galle itself during the match, a collapsing economy, zero tourism and other indicia of a failed state. Not for the first time cricket gave the people of this beautiful and unlucky island state something to be happy and proud about.

The most extraordinary Test win of the year remains, though, Bangladesh’s victory over New Zealand at Mount Maunganui back in January. New Zealand were the reigning world champions, while Bangladesh were near the bottom of the table and had never won a match in any format in New Zealand. The principal architect of victory was Ebadat Hossain, a former Air Force volleyball player, who took six for 48 in New Zealand’s second innings, belying his career bowling average of 56 – which has not improved since.

As far as white ball cricket was concerned, the main event was the T20I World Championship, which took place barely a year after the previous edition. Australia were both the hosts and the holders but they really only had a walk-on part. The outstanding sides were unquestionably England and Pakistan who deservedly met in the final. The tournament was a triumph for England’s captain, Jos Buttler, whose previous visit to Australia had been as a slightly haunted and distinctly under-performing member of Root’s Ashes side: fear of failure could have been their motto. It was all very different now, as the Test team had shown. The final was an enthralling game. Veteran leg-spinner Adil Rashid actually bowled a maiden. Inevitably, as at Lord’s in 2019 in the 50-over final against New Zealand, it was the phenomenal Stokes who was at the centre of the action at the end.

In a way though, it was the semi-final against India that showed how England were moving forward in white ball cricket while everyone else was standing still. India were constrained while batting and clobbered while bowling. Others have explained how and why. England’s players play franchise cricket all over the world and are learning all the time. India’s players, treated like princelings in their own land, don’t travel.

More records were broken at the end of the year. Two of England’s T20 heroes, Brook and Sam Curran set new standards for IPL contracts.

Reverting to England for a moment, something occurred in September that was the single most significant national event in 2022: the death in Balmoral, Scotland, of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. The passing of someone who had been a part of everyone’s life for so long was a very extraordinary thing, and every institution in the land had to decide how it was going to respond to it.

The Queen’s death became a matter of public knowledge at about 6 pm on Thursday 8 September. This was the first day of England’s third Test against South Africa at The Oval. In fact rain meant there was no play on that day. It was decided that Friday’s play would be cancelled. Cricket’s judgement was, with respect, exactly right. Saturday dawned bright and there was a great crowd at the ground. This was now of course the first day. Before play, a minute’s silence was held as a mark of respect. There then occurred what must surely have been the first public singing of ‘God Save The King” since 1952. The cricket itself was one-sided and slightly pointless but nobody who was there that day will ever forget it.

Cricket of course suffered its own losses. Trinidadian mystery spinner Sonny Ramadhin, wicket keeper/batsman Rod Marsh who made a deep mark on English cricket as well as in his native Australia; two deep-rooted Sussex cricket people, Jim Parks and Robin Marlar; the outrageous all-rounder Andrew Symonds; and David English, charity fund-raiser and cricket person par excellence were among those who passed away in 2022.

Sad though all these losses were – especially that of Symonds, who was only 46 – nothing could quite match the shock and grief felt by the cricketing world at the news of the death, aged 52, of the legendary Australian leg-spinner Shane Warne. It may seem absurd to compare Warne with The Queen, but you will understand what I mean when I say that, somehow, one did not expect them to die. There was a memorable memorial event at the MCG, marked by moving tributes from his grieving and dignified children. There was a further act of remembrance during the Boxing Day Test. This is as it should be. Warne was unique and will always be held in high esteem by genuine cricket people.

In the closing weeks of 2022 social media platforms were full, of images of a blazer-clad Warne watching a thirteen-year old leg spinner bowling in the nets. Warne was seriously impressed. “You could be playing first-class cricket by the time you’re fifteen”, he said.

That boy was Rehan Ahmed. In December he became England’s youngest ever test player, making his debut in the third Test against Pakistan in Karachi. Demonstrating Bazball-inspired (or perhaps just natural) confidence, and skill in purveying what everyone regards as cricket’s most challenging craft, he helped bowl England to victory with five for 48 in Pakistan’s second innings.

It is of course very early days. But one almost felt a baton had been passed; or, at least, a beacon of hope for the future.

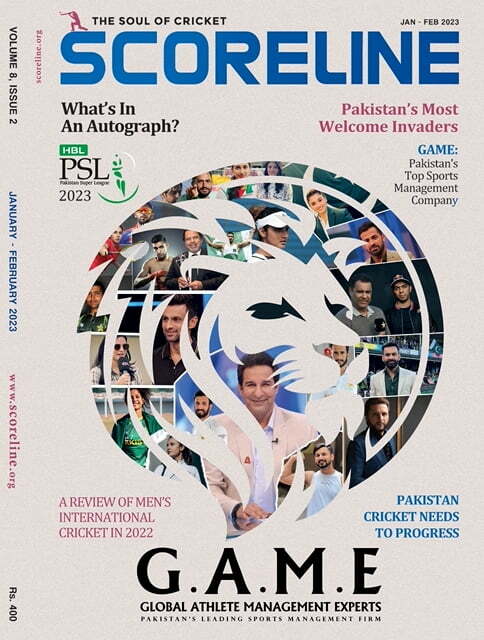

This article originally appeared in Scoreline magazine.

3 comments

Piers+Pottinger

Another superb piece with sound analysis. I often wish you wrote about golf and rugby union too.

David Edwards

This is a masterful article. The attention to detail is extraordinary and, amongst all the statistics, is Bill’s fist class English and style of writing. Wow! This piece will be enjoyed even by those who don’t have the inclination or time to follow much cricket. An outstanding achievement, Bill.

Bruce Freeman

Your retrospective brought back many of the fantastic cricket moments in 2022, but would I have retained a clearer memory of the year if there had been less tests?

There again, it’s largely Stokes’ warrior mentality that keeps his body working and we may not have too long to enjoy this golden period before he decides to step down.