The cricket world was shocked to learn of the sudden death of the former Australian batsman Dean Jones at the age of 59. He suffered a cardiac arrest in Mumbai, where he was covering the I P L for broadcaster Star Sports.

Jones’ career is curiously difficult to assess. He was a batsman capable of genuinely great achievements. Bob Simpson, no mean judge, described him as “probably the most naturally gifted batsman in Australia.” He was arguably the best one-day batsman of his generation. He had a Test batting average of 46.55 (his near contemporaries Mark Taylor and David Boon, who played far more Tests, averaged 45 and 43 respectively). Yet nobody, except perhaps the most opinionated of Victorians, is going to pick him among the 100 greatest of all time. His Test career was over by the time he was 32. His place in the Test team rarely seemed entirely secure. He made only one tour of England – often a key measure of the quality of an Australian cricketer – in 1989, when he made 566 runs at an average of 70. (Together with Taylor and Steve Waugh he was one of Wisden’s Five Cricketers of The Year, and he made the highest first-class score of the season, 248 against Warwickshire, as well as two centuries in the Tests.) He could easily, and probably should, have been on the 1985 and 1993 tours. Certainly in respect of the latter case, he made his views about his non-selection very clear.

So Jones may not have been a favourite of administrators or selectors. But with the supporters, particularly in Victoria of course, there was a very special bond. You can tell this from watching highlights of his hundred for a World XI against Australia at the MCG in 1994-95 (we are lucky that Jones was of that vintage where many of the highlights of his career are available on youtube). So here he was playing against Australia; but it is abundantly clear where the crowd’s sympathies lie when Jones is batting – Deano was their hero.

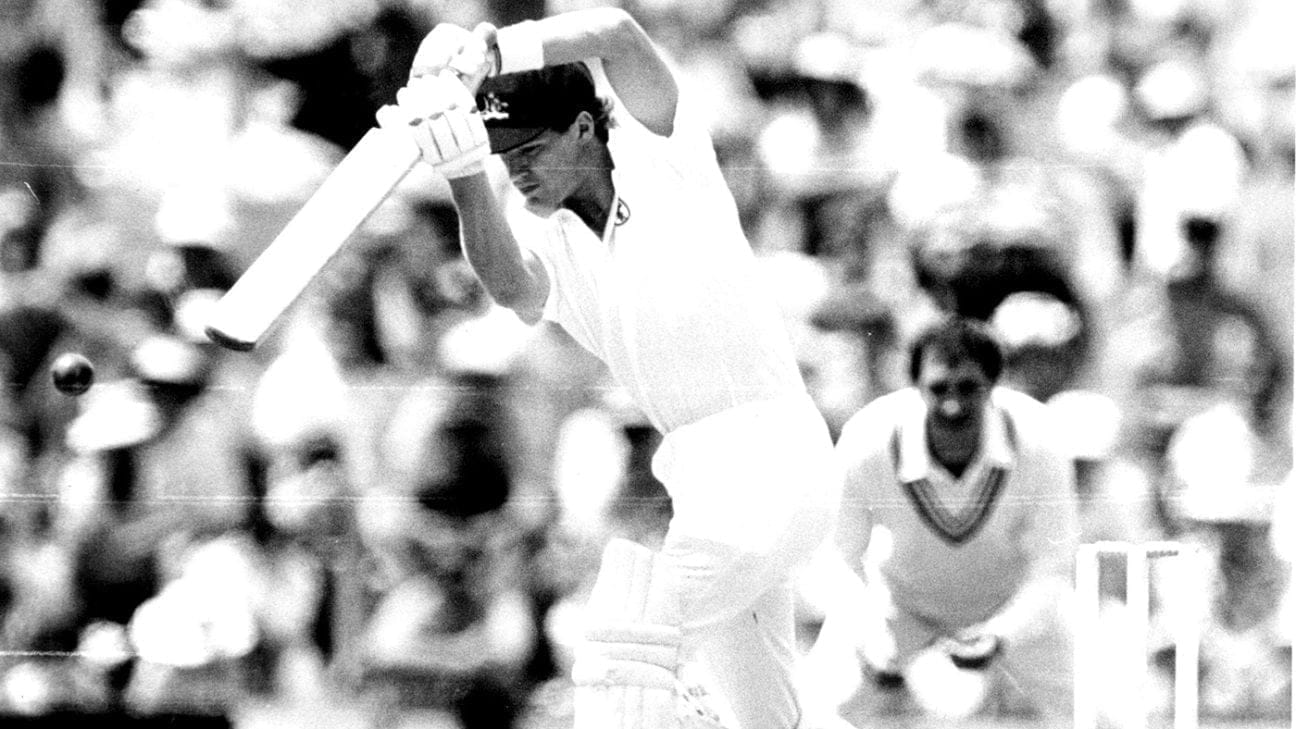

At his absolute best he was an intrepid and flamboyant batsman. He was a very good driver of the ball and a powerful hooker and puller. Very agile at the crease, with an unusually widely based stance he used his feet brilliantly against the spinners, and in one-day cricket against pacemen too. He was utterly fearless; his highest Test score, 216 against the West Indies in 1988-89, was made against an attack that included Patrick Patterson, Curtly Ambrose, Courtney Walsh and Malcolm Marshall. He probably was at his best in one-day cricket. His natural aggression, powerful stroke play and brilliant running between the wickets made him an intimidating opponent. As fellow Victorian Adam Collins said on The Final Word podcast, he would have been a star of T20. He had a touch of arrogance that can seem appealing from afar though it may be less endearing close up. Only Deano would have had the gall to ask Curtly Ambrose to remove his wristband in the middle of a spell – a spell that got decidedly faster and more lethal after that incident. He was, somehow inevitably, the first cricketer to wear shades on the field of play. Jones was no doubt “flawed” in a number of ways and more so than some of his distinguished teammates, but, on the whole, endearingly so. He could, at times, be his own worst enemy, particularly towards the end of his international career, when he kept retiring and then “de-retiring”. “Legend” was his nickname, which perhaps tells us something. At his most annoying there was something like Kevin Pietersen about him. “An infuriatingly good cricketer”, Gideon Haigh called him at the start of the 1994-95 summer, when he was striving, in vain, to get back into the Australian side. “It’s good to see him make runs. It’s good to see him fail. Nobody so imperiously self-aware should succeed all the time.” He did have his weaknesses as a batsman. Despite his occasional successes against the West Indies, he was thought to be vulnerable to high pace. And he was a poor starter. “An exciting player”, said the Victorian coach Les Stillman, in a TV documentary made about Jones in 1995, “but unpredictable”. “In what way?” he was asked. “Well”, Stillman replied, “he gets out; he gets out when he shouldn’t.”

But ask an “average” Victorian – whatever that is – what he or she thinks about Jones and you will feel the love. This is nothing to do with the fact that he was lost at such a tragically young age. He was a truly popular, almost heroic figure. He was the impetuous, outrageous, risk-taking and irritating but appealing Flashman to Allan Border’s worthy, cautious, reserved and achieving Tom Brown.

His attacking instincts notwithstanding, nobody can forget that Jones’ first great performance and surely the most epic of his career, was an innings of a very different order.

He was a prodigy in club cricket – his father had been a notable figure in the Melbourne club scene and he made a solid start in Shield cricket, earning selection for the challenging tour of the Caribbean in 1983-84. West Indies were at their indomitable best and Australia were pretty ordinary but the visitors managed to draw the first two Tests, and in the second, at Port of Spain, Jones made his debut, batting at number seven, scoring 48 and helping Border take the score from 85 for five to 185 for six. (Border scored 98 not out in the first innings and 100 not out in the second.) Jones played one more game in that series and then disappeared from the Test scene until 1986-87 when he was picked to tour India. He batted first wicket down in the first Test in Madras (Chennai) and made 210 in the first innings of the match. He batted for 503 minutes and faced 330 balls, hitting 27 fours and two sixes. Simpson called it the most courageous Test innings he had seen. Conditions were exceptionally difficult with temperatures in the mid-30s and higher throughout the game and 80% humidity. Jones was feeling the effects before he reached his century. By the time the innings was over he was barely in control of his bodily functions and when it was over spent several hours in hospital on an intravenous drip. The story goes that when he was about 170 Jones told Border, his batting partner and captain, that he just couldn’t carry on. “Fine mate”, said Border, “When you get back to the dressing room tell a Queenslander to come in; that’s who we need out here.”

The game ended in high drama, finishing as Test cricket’s second tied match.

Jones’ place was now safe for a while. He was already a fixture in the one day side and played a leading role in Australia’s successful 1987 World Cup campaign when Border’s young side really began the climb to greatness that would come to fruition under Taylor and Waugh.

Jones was a leading figure in this transitional phase, but his Test form, unlike his one-day form was a bit of a rollercoaster. He was outstanding against England in 1986-87, when Australia lost; he made 154 not out in the fifth Test at Sydney, which they won. He suffered a terrible slump in Pakistan in 1988-89, averaging 8, and struggled against the West Indies later that Australian summer until his redemptive double century in Adelaide. His greatest achievement after the Ashes tour of 1989 came in the second Test against Pakistan at the Adelaide Oval in 1989-90 when he became the 10th Australian to score centuries in each innings of a Test.

Jones remained a major force in first-class cricket after his international career was over. In 1994-95 he scored 324 for Victoria against South Australia. And in 1996 he captained Derbyshire in the county championship (he had previously played for Durham). Derbyshire, not so much the competition’s bridesmaid as its disgraced uncle who everybody hopes won’t turn up, came second. Jones made 57 first-class centuries in his career (including eleven in Tests) a considerable number for a player who spent only two and a bit years in England (the Derbyshire interlude ended rather abruptly).

In later years he was a highly regarded coach, especially in the subcontinent and particularly in Pakistan. As a pundit he was, as in his batting, potentially explosive. His crass – whatever the circumstances – description of Hashim Amla as a “terrorist” did not seem to harm his popularity outside the refined bastions of the Western chattering classes.

In 1990-91, against England at The ‘Gabba, Jones played one of his finest innings, 145 off 136 balls, with 12 fours and sixes. At the time it was the highest score by an Australian in ODIs. He had some good fortune with missed chances and the usual adventurous running, but this was a commanding and spectacular display of clean and powerful hitting. At one point he swatted a leg side delivery from Martin Bicknell one-handed over fine leg for six. As the innings developed his headgear moved from helmet, to yellow Australian one-day cap, to trademark wide-brimmed hat. Towards the end he walked down the track to a ball from Bicknell and lofted it high over long off for another six. “Just reach out and catch it Geoffrey”, said Richie Benaud from the commentators’ eyrie.

It was all there, the swagger, the athleticism, the technique, the power: Deano as he will always be remembered.

6 comments

Trevor

Very interesting Bill and a reminder of a batsman who probably does not get the credit he deserves. To average 46 in that era was a substantial achievement.

Zafar Ahmadullah

One other thing I would add would be his fielding. In my opinion he was one of the pioneers in the switch to modern athletic fielding.

Bruce Freeman

You’ve made me want to watch the recordings of his innings. But there again, he’s an Aussie and it would be through gritted teeth.

Perhaps if he ran out Border….?

Nick OBrien

My thanks and comments very much as above. Was he feared and respected more outside Australia than in? As a New Zealander I was always happy to see his innings end, better still if he wasn’t in the team. He may have ‘got out when he shouldn’t’ but every innings you knew he had huge ambition.

Piers Pottinger

A most informative piece about a most talented player. As ever extremely well written

Malcolm Merry

How was he in adversity? Boxing Day 1987 Australia, unexpectedly 1-0 down after 3 tests, desperately tried to hit England’s bowling into submission. 143 all out before tea. Jones held the innings together though with a gritty 59.