Whatever your interpretation of T S Elliot’s famous line, April is a month I normally look forward to. The 2020 edition of Wisden – the 157th – is out. In England, even the weather, by all accounts, is lovely.

But this year is different of course. There is something precious and almost sac about the start of the cricket season. Cricket is a game rife with ritual and ceremony – on the village green and at the Indian Premier League, not just at Lord’s and the MCG. Part of that ritual is the necessary preamble – cutting the grass, rolling the square, whitening the crease lines, sorting out your kit, organising the tea roster, making sure you’ve got an eleven for the first match.

None of that will happen this year. Who knows, perhaps there’ll be some hurriedly cobbled together fixtures – at international, county and recreational level (I fear we can say goodbye to schools and universities for 2020) – in August and September, but even that seems unlikely. The Hundred? Just push it to 2021.

April itself has never been a huge cricket month in England, for obvious reasons. It is, after all, the summer game. April has not seen a day’s Test cricket in England, even in the era of twin Test tours, which started in 1965 when New Zealand and South Africa toured. (in 1912 there was the Triangular Tournament, involving England, Australia and South Africa: the first Test, of nine, started on 27 May.

England has hosted the Men’s World Cup, the tournament being followed on each occasion by a (usually three-or four-match) Test series. The first three tournaments, in 1975, 1979, and 1983, were relatively short, and none started earlier than 7 June. The 1999 competition was more ambitious, and started on 14 May. The 2019 Men’s World Cup, probably the best of all, started as late as 30 May, and finished on Bastille Day (I remember this because during what was unquestionably the most dramatic cricket match of my lifetime, I was in the south of France). The World Cup was followed by a Test against Ireland and a full Ashes series, which just shows how crazy the schedule has got; perhaps it really is time for a break.

First-class cricket is different of course with the scheduling pressure of all the different competitions it is not unusual nowadays for the earliest fixtures to be in March.

One of the most exclusive first-class batting records, still immortalised in the physical Wisden (a lot of records have moved online) is the achievement of scoring “One Thousand Runs in May”. Only three batsmen have done this: W G Grace (1895, when he was 46), Wally Hammond (1927) and Charlie Hallows (1928).

Five other batsmen (including Don Bradman, twice, in 1930 and 1938) have achieved the subtly different feat of scoring a thousand runs before the end of May, the most recent being Graeme Hick in 1988. With the continuing reduction of the Championship programme it is difficult to see this milestone being achieved again even if the season were to start in February.

The inclusion of Bradman in this list reminds one of what tours used to be like. The tourists played all the counties some of them twice, MCC, the two ancient Universities, the Minor Counties and festival games; of course tours had to start in April, so it could all be fitted in. To cover the Ashes tour of 1953 Jack Fingleton arrived, by ocean liner to Southampton, as early as 13 April.

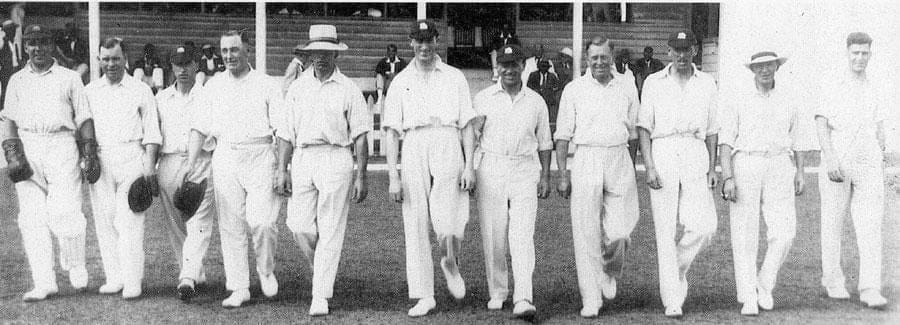

The last “proper” tour was probably the Ashes tour of 1993, made famous by Shane Warne’s emergence as a cricketing genius. The tourists played 21 first-class games. Four of the batsmen made a thousand runs – David Boon, Mark Waugh, Michael Slater and Matthew Hayden (who did not play in a single Test). Warne took 75 wickets. The tourists’ first game was against an England Amateur XI (which included Mel Hussain, Nasser’s brother) at Radlett on 30 April.

England’s initial Opponents in Test cricket were Australia and South Africa, countries where cricket in April is not ideal. The first April Test was played as late as 1929-30, in fact on – wait for it – 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 April 1930. This was the fourth Test between West Indies and England at Kingston, a remarkable game mentioned previously on Pavilion End (as I am sure many of you recall). The game was, if not memorable then at least noteworthy, for a number of reasons. The England opener Andy Sandham, made 325 – Test cricket’s first triple century – in what turned out to be his last Test appearance. It was also the final appearance for England of the extraordinary Yorkshire all- rounder, Wilfred Rhodes, who was 52 years old and had match figures of two for 39 in 44.5 overs. George Headley, largely forgotten now but surely one of the greatest of all West Indian batsmen, as a career average of 60.83 indicates. The result? Ah, eight days wasn’t quite long enough; it was a draw.

The game, though, set a trend in a number of ways. First, most April Tests have taken place in the Caribbean. India is too hot, though evenings are obviously acceptable for the IPL. Pakistan used to host the odd series in April. Sri Lanka is hot and sticky all the time so it may as well be April as any other month. Rather astonishingly Ireland played its inaugural Test, against Pakistan at Malahide in 2018, as early as 11 May.

But it’s the West Indies who have staged most April Tests. And another trend, set by Sandham, has been the penchant for big scores. Brian Lara made both his record scores, at Antigua against England, in April (375 in 1993-94 – see feature image – and 401 in 2003-04). In 2004-05 on the same ground Chris Gayle made 317 against South Africa.

If you had to pick a bowler for April it would probably be Curtly Ambrose. He demolished England in a crucial game at Barbados in 1990-91 with a second innings eight for 45 that turned the series. In his splendid Berkmann’s Cricketing Miscellany (Little, Brown, 2019), Marcus Berkmann picks West Indies v Australia at Port of Spain, the third Test of the 1994-95 series, as his favourite April Test. This was an enthralling series, won two-one by Australia to depose West Indies as unofficial. world champions. This game, though, was won by the hosts, by nine wickets, thanks largely Tom Ambrose who took five for 45 and four for 20. This was the game in which there was a memorable confrontation between Ambrose and Steve Waugh, which looked at one point as though it might come to blows. Berkmann quotes Waugh as saying “It’s Test cricket. If you want an easy game, go play netball.”

(I greatly enjoyed the Berkmann book but there is a silly mistake on the very first page.)

If I were to choose a favourite April Test performance – as much for its sheer unexpectedness as anything else – it would be a performance in the fifth Test between West Indies and England at Port of Spain in 1973-74.

These were not two vintage sides but they produced an interesting contest. In the English summer of 1973 Rohan Kanhai’s side had won a three-series contest two-nil. Ray Illingworth then stepped down as England captain to be replaced by Mike Denness. The proven Test performers included the opening batsmen Dennis Amiss and Geoffrey Boycott – the latter, if not disgruntled then far from gruntled at being overlooked for the captaincy – middle-order batsman Keith Fletcher, all-rounder Tony Greig, who was vice-captain and keeper Alan Knott. Only Boycott, Knott and Pat Pocock of the MCC party had toured the Caribbean before. West Indies were in a fallow period. Kanhai and Gary Sobers were arguably playing one series too many, but they produced two new batting stars in Lawrence Rowe and Alvin Kallicharan.

West Indies won the first Test at Port of Spain, veteran off spinner Lance Gibbs taking six wickets and Sobers three in England’s second innings. There were big hundreds for Kallicharan and Amiss. (This was the game where there was a huge row after Greig threw down the stumps at the bowler’s end as Kallicharan was walking down the pitch in the apparent, and not unreasonable belief that play was over for the day. Greig, appealed, successfully, for the run out. It took several hours of negotiation to get the appeal withdrawn and the decision reversed.

The next three Tests were high-scoring draws. Amiss made 262 not out in the second Test at Kingston, where the local hero, Rowe, made 120. At Bridgetown, in the third Test Rowe made 302 in the hosts’ only innings. England, who batted first, were reduced ton130 for five by left armer Bernard Julien, but Greig and Knott added 163. Greig made 148. In West Indies’ massive 596 for eight, Greig took six for 164 in 46 overs. He also caught Sobers for nought off Bob Willis, the great man’s first Test duck at his home ground. Greig became the first England player to make a century and take five wickets in an innings in the same Test.

Rain ruined the fourth test at Georgetown but not before England had made 448 in their only innings (Amiss 118, Greig, 121).So England had to win the fifth Test, back at Port of Spain, to square the series. The game started (in case you were wondering) on 2 April 1974. (The first match of the tour had started on 23 January.)

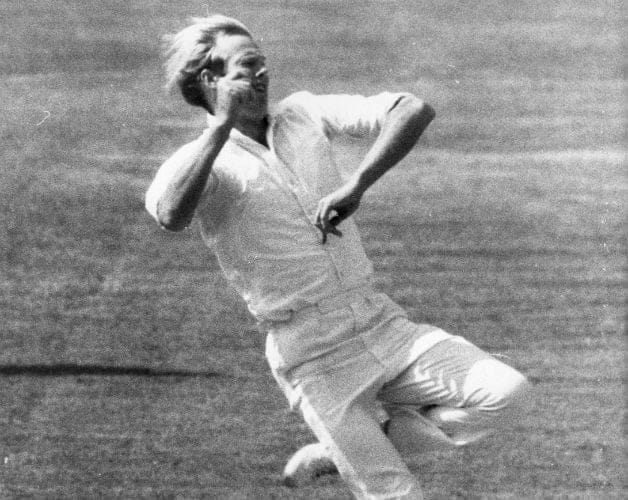

Greig had made his England debut under Illingworth in the 1972 Ashes and quickly made himself undroppable. South African born, to a Scottish RAF pilot father and South African mother, he was 6’7” tall, blond, and charismatic. He was an aggressive right- handed batsman, a useful second or third change seamer – “his hectic approach”, according to Wisden,” was a mass of pumping legs and jutting elbows.” He was a brilliant fielder in any position.

Greig, as I said, was a seam bowler. But in the second Test at Kingston he started experimenting with off spin, just as a defensive measure. This was how he bowled at Bridgetown. And it was to prove decisive at Port of Spain.

The wicket at Port of Spain was known usually to favour the spinners and England picked two “regular” off spinners, Pocock and Jack Birkenshaw, as well as Greig and slow left armer Derek Underwood. (Birkenshaw would have been accustomed to this situation. It was said that when Illingworth, also an off spinner joined Birkenshaw’s county, Leicestershire, as captain, he would put “Birky” on to see if it was turning; if it was, he’d take him off and bowl himself.)

It was a six-day match. Denness won the toss and England batted. Boycott, who had had a quiet series, should have been run out for nine, but Kanhai threw to the wrong end. Boycott made 99 in six hours 25 minutes; at one point he went 50 minutes without scoring. England made 267.

West Indies responded with 305, of which Rowe made 123, fellow opener Roy Fredericks 67 and Clive Lloyd 52; nobody else reached 20. At one stage they had been 224 for two. Greig’s brand of off-spin proved to be almost unplayable. His great height enabled him to get peculiarly difficult bounce; now he really was an attacking bowler. He took eight for 86 in 38.1 overs. The powerful middle order of Kanhai, Sobers, Lloyd and Murray was swept away in 20 balls for six runs.

When England batted for a second time it was once again all Boycott. This time he made 112 in six and three quarter hours, before being bowled by Gibbs, the veteran’s only wicket in 50 overs. England made 266 and West Indies had to make 224 to win.

When the final day started West Indies were 30 for none and all results seemed possible (rain had been a constant threat). Greig opened the bowling with his off-spin and proved again to be the major figure, finishing with five for 70 in 33 overs. Sobers and Murray held England up for a while but they won by 25 runs with an hour to spare.

Greig scored 430 runs at 47.77 in the series, and took 24 wickets at 22.62. No other England bowler took more than nine wickets (9) or averaged less than 48 (Birkenshaw). On the tour he took 12 catches, more than anyone else except Knott.

Later Greig was to be an inspirational captain of England, Kerry Packer’s front man for World Series cricket, and an influential TV pundit. In short, he was one of the most significant cricket people of his era.

With no cricket to look forward to this April, perhaps it’s time to reflect again on who has been England’s greatest all-rounder?

4 comments

David Khor

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief,….

Nambi

Thank you Bill, excellent reminiscences

Piers Pottinger

A charming piece once again to lift our spirits in this joyless time.

I can recall watching a cricket match on Winchester College’s beautiful ground set beside the glorious water meadows. It was early April and term had just started. After three overs it began to snow. Play continued for two more overs before being abandoned in a blizzard. A memorable match !

Alex Deverell

Thanks so much Bill for your excellent blog – very sad not to have any cricket to enjoy this summer but looking forward to more of your brilliant thoughts on this game we all love.