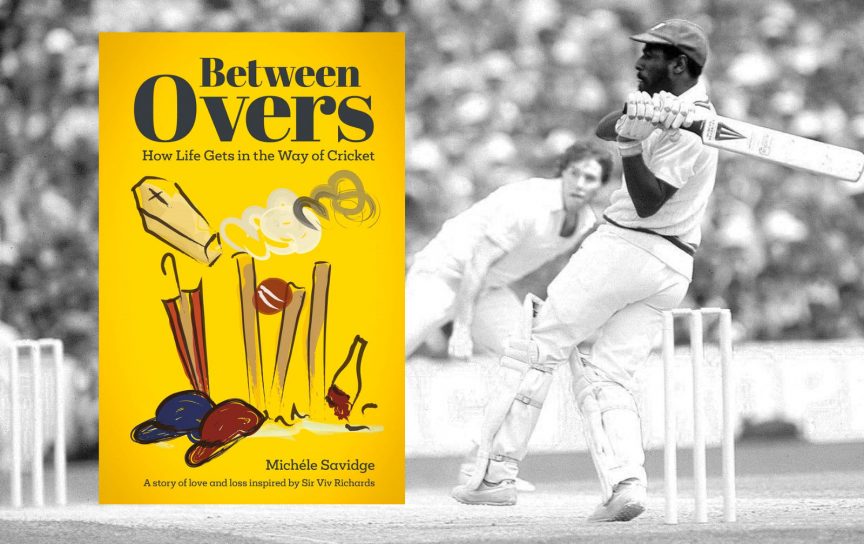

Between Overs: How Life Gets In The Way Of Cricket

By Michéle Savidge

Pitch Publishing, 351pp

“Are you part of the catering team?”

This question, asked by a former MCC secretary and retired lieutenant colonel, provides an eloquent backdrop to the journalistic career of Michéle Savidge, who tells the story of that career in her engaging memoir, Between Overs.

We are currently in a golden age of women cricket writers. In England alone, Tanya Aldred, Emma John and Elizabeth Annon stand comparison with any of their male counterparts, as writers, reporters and news hounds.

This, however, is a relatively recent development. The rise of women cricket writers has in a sense kept pace with the rise of women’s cricket generally but there is no real connection. (Savidge makes no mention of women’s cricket in her book.) Michéle Savidge was a trailblazer.

It is inconceivable that today’s women correspondents have not all had the same sort of experience as that recounted by Savidge – who was, at the material time, an experienced sub-editor on the Evening Standard. That is, simply, how things were, probably are (Savidge recounts a similar tale from the 2019 Men’s World Cup). The legal profession is full of women but I know a number of brilliant female lawyers who have been on the receiving end of questions such as that put to Savidge. Such questions are not asked because of malice, or even personal indifference. It is a mixture of ignorance, arrogance and often unconscious discrimination.

Much more disturbing than that innocent question are the accounts of sexual harassment suffered by Savidge at – literally – the hands of various leading cricket personalities. Savidge is not in the naming and shaming game, though she gives some tantalising clues. She has nothing to worry about from our learned friends – indeed, one of these ghastly individuals is no longer with us; and what would be the purpose of naming them. The main point seems to be the astonishment of the Savidge of 2022 that the Savidge of the late ‘70s and early ‘80’s could have been so innocent.

Back then she really was on her own as a female cricket journalist. Largely because of her cricket-loving father, a huge influence on her life, she developed an obsession with the game from a young age, a sentiment considerably encouraged by a first sight of the young Vivian Richards playing in a village match in Somerset in the early 1970s. After studying English and Media Studies at university (where? – I think we should be told), she landed a job working for Christopher Martin-Jenkins at The Cricketer. She loved the job, and got more and more experience, and only left because she simply could not afford to stay. She subsequently worked at the magazine Cricket Life before moving to the Standard.

Savidge loves cricket with a passion, as her subtitle indicates. As she says more than once, cricket is more, much more, than a mere distraction.

But even cricket has its bleaker moments. For Savidge, there was not only the trauma of sexual harassment. She has become an impassioned opponent of racism in the sport.

Her hero worship of Richards is a major factor here. The great man himself is well aware of her views on him. She has interviewed him numerous times, once, remarkably, on the same day as his presumably rather more fraught encounter with the Daily Express reporter James Lawton. Devotion to Viv (“the guiding light”) became devotion to the West Indies team generally, and in particular their fast bowlers. (This has become a special subject for Savidge; she has co-authored a book on it).

On the West Indies’ 1976 tour of England there was a wake-up call for the young Savidge. It came in the form of the (South African-born) England captain Tony Greig’s prophecy that his team would make the visitors “grovel”.

The repercussions of this statement of Greig’s are too well known to be rehearsed here. Suffice it to say that it opened Savidge’s eyes to the iniquities of racism, to which, let’s face it, cricket can hardly be said to be a stranger. She gives a number of examples of discriminatory reporting, notably by David Frith, whose custodianship of Wisden Cricket Monthly certainly gave rise to some unfortunate editorial decisions.

That said, there is surely a balance to be struck here. It must be possible to criticise the West Indies pace quartets without being racist, in the same way as it must – mustn’t it? – be possible to criticise Israel’s Palestinian policy without being anti-Semitic.

Savidge waxes lyrical about Michael Holding’s outstanding performance at The Oval in 1976, when he took 14 wickets on an easy-paced pitch. But she says nothing about the Saturday evening of the Old Trafford Test, when Holding, Andy Roberts and Wayne Daniel launched a blistering attack on the England openers, Brian Close and John Edrich. She says that Clive Lloyd’s side never lost a Test series under his leadership between 1974 and 1985 except to Australia in 1975-76. Actually that’s not correct. They lost 1-0 to New Zealand in 1979-80, a series made memorable by poor behaviour from the West Indians. There is a celebrated photo of Holding kicking a stump out of the ground during one of the Tests. We can all agree that Holding is incapable of performing an inelegant act. But most of us would also agree that this is not an acceptable way to express one’s disappointment at an umpiring decision.

Focussing in this way on sexual harassment and racism might suggest that this book is dark and depressing. In a sense it has to be said that there is an element of that. Right from the start of the book a recurring theme is Savidge’s extremely strong and close relationship with her parents, especially her father but her mother too. The seismic events in the narrative are their respective deaths and the impact their passing had on their daughter. To a considerable extent this is a book about grief. One senses that writing the book was a cathartic experience for Savidge; writing it was more important for her than getting it published. There are other issues that are remembered in detail too, such as a failed pregnancy, and post-natal depression. But even when describing the darkest times, Savidge writes with a light touch and in a deliciously self-deprecating style. At one point she is asking herself why such and such a thing was done or not done before her mother’s death, then she suddenly says “And why did Geoff Boycott run out Derek Randall at Trent Bridge in 1977?”

Even so – and I realise as I write this that I might be perceived as slipping into Lt-Col mode – I would personally have preferred more cricket and less of the highly personal material. There are times when one really does feel like an intruder. When we are told, towards the end of the book, that Savidge’s brother is transitioning, one is tempted to say enough is enough. But the main reason for my preference is that Savidge is a brilliant cricket writer and she leaves us wanting more. (She could perhaps do a second volume premised around the not inconsiderable personal problems faced by her children.) Her writing is technically sharp, astute from the human perspective, elegant and easy to read. Her description of the final day of the Ashes Test at Headingley in 2019 – Ben Stokes’ day – is as good as any I have read. She is brilliant at capturing atmosphere, whether it is the Recreation Ground at St John’s, Antigua, or Lord’s for the 2019 Men’s World Cup final – again her description of the climax to that extraordinary day is quite brilliant, especially in reference to Stokes.

Her Fantasy XI is an actual XI – the West Indies team that faced India in four of the five home Tests in 1982-83; Winston Davis replaced Joel Garner in the fifth. I sort of get it, and it is good to see one of my favourites, Larry Gomes, in the side. But a fantasy West Indies team without Gary Sobers or Brian Lara somehow does not seem right.

Sobers does make it to her Fantasy Lunch XI, which is meant to comprise cricketers who will sparkle at the table rather than the crease. There are some odd choices there too. I would not expect WG Grace or Sachin Tendulkar to be overflowing with Wildean aphorisms. There are two shoo-ins : Ian Botham, who is there to provide the wine, and John Arlott, who is there to drink it.

Lara is allowed his moments. Savidge was in Antigua to see his record score of 375 against England. And at the end of the book, when she is trying – successfully it seems – to persuade a novice – a cricket guinea pig – of the true wonder and significance of Test cricket, the match she chooses is West Indies’ miraculous one-wicket victory over Australia at Barbados in 1998-99 when Lara made 153 not out.

In a chapter entitled “Trent Bridge – Lotus Land for Batsmen … and My Father” Savidge writes movingly about her father’s desperately sad descent into dementia. Perhaps I am missing something but I could not find a single reference to Trent Bridge in the chapter, although there are accounts of Savidge watching cricket with her father at Lord’s and Edgbaston, and there are references to his beloved Nottingham Forest.

In some ways the most entertaining chapter is the one on Peter O’Toole (“The Man I would Have Run Away With”). I too remember his astonishing stage performance as Jeffrey Bernard. I wonder if Savidge has seen one of his last films, Dean Spanley, which features cricket being played in the house – not the grounds – of an Indian prince. “Damn fool game, cricket”, says O’Toole’s character, “Too many rules”.

This highly readable book, although in a sense a celebration of the achievements of a clearly remarkable woman, is in fact dominated by three men. A distant third is Michael, Savidge’s I suspect – move over Lt-Col – long suffering husband (“an un reconstituted Fred Flintstone of a man”). Second of course is Viv – she writes exceptionally well at various points about every aspect of his cricket. But first, by a country mile, is her father, and it is he who brings the book to a close.

“And then my father stands up, rubs the small of his back as is his habit, and I watch him walk towards the pavilion.”

Review by Bill Ricquier

Share this Post