Is cricket the most literary of games?

There is obviously no real answer to this question. For all I know there is a wealth of literature concerning football – The Beautiful Game – but somehow, I doubt it. There is some terrific journalism, but that’s a different thing.

There are a lot of cricket anthologies, some good, some not so good. Unquestionably the best is The Cricketer’s Companion, edited by Alan Ross. Ross was the cricket correspondent of The Observer, but he was never “just” a newspaperman. He was a genuine man of letters, a distinguished poet who for many years was editor of The London Magazine, renowned for its reviews of books, the arts and cultural life generally.

The Cricketer’s Companion, published by Eyre & Spottiswoode in 1960, is a wonderful book. The first section, “Cricket Stories”, has extracts from work by, among others, Dickens, Mary Russell Mitford and L P Hartley, though nothing from the best of all cricket stories, “Spedegue’s Dropper”, by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. There follow sections on great players and great matches, and the volume concludes with seventy pages of cricket poetry, with contributors including Byron (who played at Lord’s), Siegfried Sassoon, P G Wodehouse, John Arlott – a poetry producer at the BBC before he became perhaps the most eloquent and distinctive of all radio sports commentators – Norman Nicholson, and Ross himself. Of a later vintage, Ross’s poem, “Late Gower”, cannot fail to bring a lump to the throat. Harold Pinter wrote some very effective cricket poetry (“Hutton and the Past” perhaps the best). One poem runs, in its entirety:

I saw Len Hutton in his prime. Another time, another time.

The story goes that Pinter telephoned his friend, the cricket-loving playwright Simon Gray, to ask what he thought of his new poem. “I haven’t had time to read it”, said Gray.

If there is an equivalent in football – or golf, or tennis – to The Cricketer’s Companion, I would love to read it. (To be fair, the golf writer, Bernard Darwin, was more than a mere journalist; to prove it, he wrote an acclaimed biography of The Great Cricketer, W G Grace.)

The book would probably have to be the starting point if I were building a cricket library from scratch.

I say “probably” because there is another obvious starting point and that is a volume – or more – of Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack. Wisden, the “cricketers’ Bible”, currently in its 154th edition, is unique, and difficult to describe effectively in a few sentences. As its name indicates it is, on the one hand, a gazetteer, a record of global first-class cricket over a particular period of time – in recent times, effectively a calendar year. This involves full scorecards and reports of “major” matches, including domestic (county) cricket in England and detailed general surveys, and averages, relating to domestic cricket elsewhere. This takes up the lion’s share of the book and this aspect of Wisden has only changed in the sense that the volume of cricket played around the world has grown enormously over time.

Another thing that has stayed the same is The Five Cricketers of the Year feature, chosen by the editor every year since 1897. A player cannot be picked twice. Traditionally focus has been on performances in the relevant English season. The 2017 edition features two genuinely great players who would certainly not have had another opportunity to appear, the Pakistani duo Misbah-ul-haq and Younis Khan.

In other respects, Wisden has changed considerably. But unlike most things, especially when subjected to purported “upgrading”, Wisden is getting better. First, the comment section, historically something of a mixed bag, is now consistently of the highest quality. There were usually a few good articles in Wisden. Editors now are much more adventurous than they were, and there are more quality writers to choose from. The Test match reports and major obituaries are often superbly written.

The other big change concerns the Records section. Part of the point of Wisden has been its role as a journal of record and statistical authority. Historically the legendary “Births and Deaths” section, recording those crucial dates for every first-class cricketer, formed a critical part of the volume. In the 1935 edition, Births and Deaths took up eighty-eight pages. By 1967 it had come down to fifty-seven, with detailed instructions as to which editions to consult to find the missing details. Now the whole thing is more focussed and streamlined. There is editorial recognition of the amount of detail available online, including Wisden’s own website. In short, the previous level of detail regarding Test and first-class records is no longer available in the book itself. Still, if you know your way around it – it’s not straightforward – Wisden remains a statistical goldmine.

A decent cricket library without Wisden is that rarest of things, a genuine oxymoron. I did mention that it is difficult to explain what is so special about it. All I can say is that, if you are genuinely interested, pick one up and have a look at it. Then, see how long it takes before you’ve had enough.

A record of a sport must be at least as much about pictures as about words (Arlott’s unique talent was to be able to produce both simultaneously). Cricket has a supreme picture book, the sumptuous Pageant of Cricket, produced by the Anglo-Australian writer David Frith (Macmillan 1987). Beginning at what Frith describes as “the mists of antiquity” – an engraving of Edward I, who apparently encouraged his son to play a game which Frith thinks must have been an ancestor of cricket – and finishing at the time of publication, the book contains an astonishing range of pictures, enriched by Frith’s pithy but deeply knowledgeable captions.

Now, to “normal” books. Sometimes, when there’s a subject matter you love, you need something that takes you outside it, and gives you a bigger picture. Cricket literature has that something: Beyond a Boundary, by the Trinidadian Marxist philosopher and historian C L R James. Again, this is not an easy book to classify. It begins as a memoir of the author’s early years in Trinidad, following the cricket and cricketers of the West Indies. The broader context, though, of race and politics in the Caribbean, is never far from the surface, and these themes are given a perspective broader still as James ranges over cricket history in England and the colonies. James was at the forefront of a campaign to install Frank Worrell as the first black West Indian captain. Arlott, reviewing the book (Hutchinson, 1963, but reissued many times since) in the 1964 Wisden – he did all the Wisden book reviews between 1950 and 1991 – described it simply as “the finest book ever written about the game of cricket”.

Cricket history has been a fertile source for many authors – John Major and the former Jamaican Prime Minister, Michael Manley, among them – but some of these can be a little turgid for someone starting to develop an interest. If one is looking for passion, learned research and a winning prose style, look no further than Peter Oborne’s Wounded Tiger (Simon & Schuster, 2014), about the controversial, rollercoaster history of cricket in Pakistan.

There are lots of books about cricket matches. The classic format was the tour book. There are dozens, if not hundreds of these, but the masters of the genre were Ross and Jack Fingleton. If I had to nominate one cricket book to take with me to the proverbial desert island it might well be Ross’s Australia 55, his account of Hutton’s triumphant Ashes tour of 1954-55. Ross is very good on the cricket, but there is so much more to the book than that. It is a genuine and beautifully crafted travel book, as much about Australia as about bat and ball.

Fingleton was special. For a start, he was a top-class player, opening for Australia in eighteen Tests. He was a professional journalist – a political commentator. In 2001, as part of his “The New Ball” project the English writer Rob Steen produced a brilliant volume called The Write Stuff. He asked twenty-two authors and cricket people to nominate one scribe each, write about him or her and nominate a particular piece for inclusion in the book. Fingleton was the only writer to be selected by more than one contributor.

He played in the Bodyline series and wrote about it in Cricket Crisis. He wrote two marvellous books about tours of England by Australia. The first was on Don Bradman’s Invincibles of 1948, Brightly Fades the Don. Fingleton was no friend of Bradman but this, as one would expect, is a thoroughly objective account. My favourite, though, is about the next tour, in 1953, The Ashes Crown the Year. I’m not sure how many times I have read this book, but I could read it again tomorrow. Fingleton’s understanding of character and context gives the book the vibrancy of a well written novel.

Tour books don’t work anymore because tours have become so boring. Even Alan Ross would struggle to make a description of Ben Stokes and Jonny Bairstow playing Call of Duty interesting. The last authentic tour book was a fitting one, Pundits from Pakistan (Picador, 2005), Rahul Bhattacharya’s finely crafted account of India’s tour of Pakistan in 2003-04.

The modern successor to Ross and Fingleton is the great Australian Gideon Haigh. He produced books on every Ashes series from 2005 to 2013-14, and they are indispensable. It is intriguing that he did not do a book on the 2015 series. Perhaps he shared the not uncommon view of the quality of the cricket on offer.

An honourable mention for a small masterpiece by the distinguished social historian David Kynaston. W G’s Birthday Party (1990, Chatto & Windus) is about a single match played between the Gentlemen and the Players at Lord’s in July 1898 to celebrate the fiftieth birthday of W G Grace. Kynaston’s eye for the quirky detail has a field day in what is not just an account of the match itself but also of the richly varied lives of the twenty-two participants.

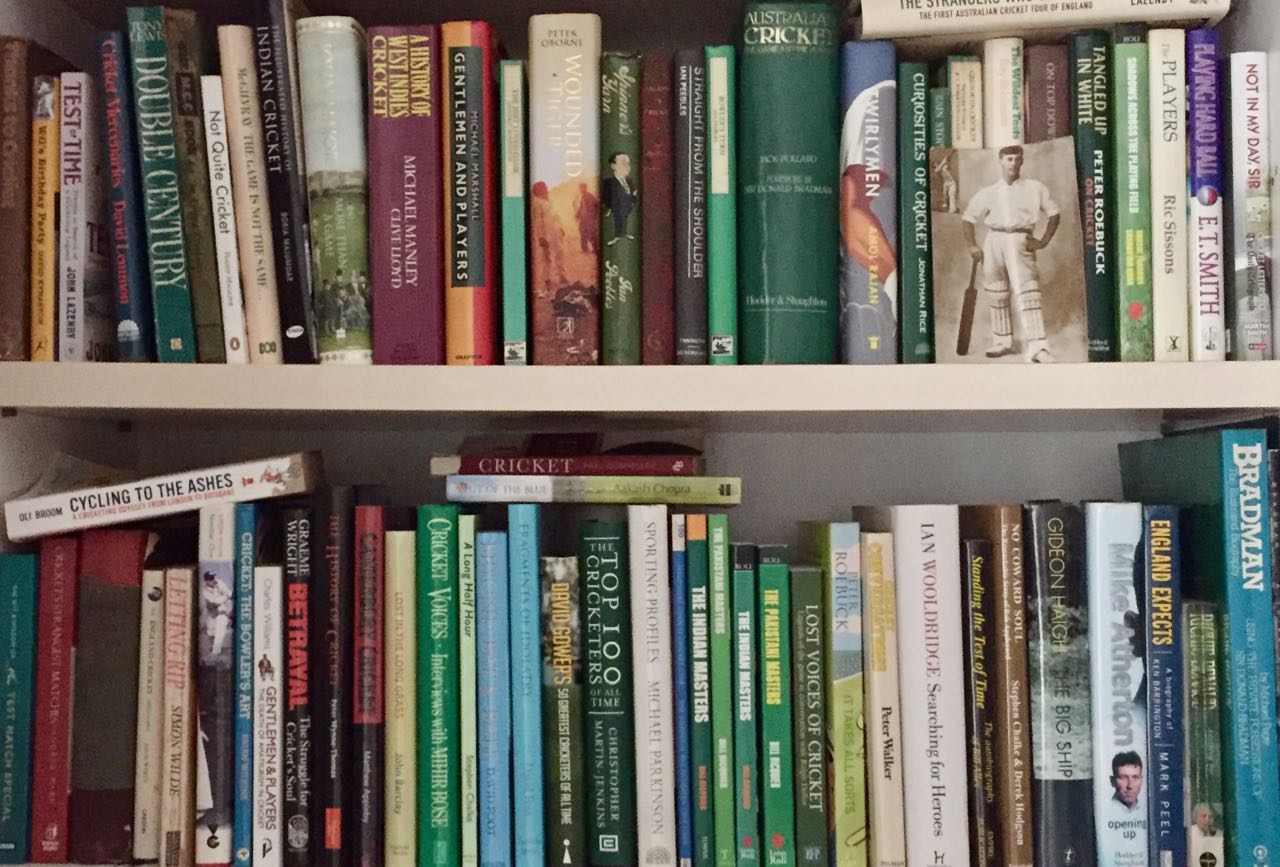

Of course there is no shortage of books about players, biographies, autobiographies and memoirs. Again, it is a mixed bag. On my own shelves I have eight books about Shane Warne, most of them unreadable, in particular the ones purportedly penned by the great leg spinner himself. As Warne has claimed – rather proudly – never to have read a book in his life he can hardly be held responsible for any editorial or stylistic shortcomings, but you get my drift. The main exception is Haigh’s On Warne (2012, Simon & Schuster), not a biography but a series of essays on aspects of Warne’s career.

If I had to pick a biography it would probably be Fred Arlott’s book on Fred Trueman. Lyrically written and richly, sometimes hilariously anecdotal, it is a fine account of Trueman’s career, although it does not pretend to look beyond the cricket. For a deeper examination of a sportsman’s life one can do no better than Duncan Hamilton’s moving biography of the nan whose career was made and broken by Bodyline, Harold Larwood (2009, Quercus).

As for books by cricketers, obviously quality is very mixed. Usually a lot depends on the ghost. But not always. Steve Waugh has been a prolific writer and his tour diaries are excellent. His autobiography is a real achievement; it weighs in at 801 pages, so you have to be a real fan to make it through to the end. Of the ghosted variety Marcus Trescothick’s is exceptional. Coming Back To Me (2008, HarperSport), with Peter Hayter, gives a moving and frank account of the former England batsman’s travails with depression. I think, though, it is just pipped by The Test (2015, Yellow Jersey Press), an account by Simon Jones of his career but using the 2005 Ashes as a peg. It is quite brilliantly ghosted by Jon Hotten: Jones’s voice comes through, clear and authentic. Often deeply moving too, the most effective parts of a highly effective whole are the descriptions of the games in that extraordinary series; the intensity of taking part comes through in a remarkable fashion.

Well informed readers might have noticed that there is one name I haven’t mentioned yet. It is true that no respectable cricket library would be complete without something from (Sir) Neville Cardus. Of course he features in Ross’s anthology, and in all worthwhile anthologies, but that is probably not enough.

Cardus was the first great cricket writer and the first modern one. Anybody who has written about the game since the Second World War owes something to him. Largely self-taught he became both the music and the cricket correspondent of the old Manchester Guardian (making him a sort of rich man’s Michael Henderson). His style was unique and often very funny. Much of his work remains available courtesy of The Souvenir Press.

His early books often combined essays on players and accounts of series. A classic example is Good Days, which has about thirty essays plus Cardus’s account of the 1934 Ashes.

A classic essay is “The Noblest Roman”. This is a piece on the England and Lancashire batsman, A C Maclaren, who made 424 against Somerset in 1895. The final paragraph gives you the flavour of Cardus’s style:

He was the noblest Roman of them all. The last impression in my memory of him is the best. I saw him batting in a match just before the war; he was coming to the end of his sway as a great batsman. And on a bad wicket he was knocked about by a vile fast bowler, hit all over the body. And every now and then one of the old imperious strokes shot grandeur over the field. There he stood, a fallible Maclaren, riddled through and through, but glorious still. I thought of Turner's "Fighting Temeraire", as Maclaren batted a scarred innings that day, and at last returned to the pavilion with the sky of his career red with a sun that was going down.

Bill Ricquier