The second Ashes Test, at Lord’s, was in many ways as remarkable as the first. England made the running for much of the game at Edgbaston. They seemed to have Australia at their mercy in the final session of the first day when Joe Root was in imperious form, until Ben Stokes declared. On the final session of the final day , after numerous twists and turns, it really looked as though England were going to win until Pat Cummins wrested control of the match from them.

Lord’s was different. Asked to bat in overcast conditions, Australia scored 416, with Steve Smith making his 32nd century in his 99th Test. In hindsight, the critical passage of play came late on the second afternoon, in glorious conditions for watching cricket and, it seemed, for batting. England’s openers had got them off to a flying start, and after 37 overs they were 188 for one. That one wicket had been gifted to the Australians by Zak Crawley, dancing down the wicket to Nathan Lyon and missing. Before long they were 222 for four, with three top-order batters out trying to smash the persistent short-pitched bowling. Ben Duckett fell for 98. Root was the most culpable, caught hooking what turned out to be a no-ball, and then caught again a few overs later, with no reprieve. By this time Lyon had hobbled off with a calf injury and it did seem that a little patience might bring dividends.

England conceded a lead of 91. Once again, as they kept doing last year, their not especially threatening looking attack bowled Australia out for a second time, leaving them with a target of 371. History was against them, and at close of play on the fourth evening they were 114 for four.

The general mood in the members’ queue on Sunday morning was that the game could be over by lunch. But one of the not out batsmen was Stokes.

Oddly enough Stokes had been one of the not out batsmen on that second evening. After the mindless period of batting by the top order Stokes had come in to join Harry Brook, and batted extremely sensibly, making 17 off 57 balls, with one four. Then on Friday morning he was out to the first ball he faced, from Mitchell Starc.

On Sunday Duckett and Stokes started confidently. Josh Hazlewood, Starc and Cummins bowled demanding spells, but within an hour Cameron Green was bowling from the Pavilion end with no close fielders at all. Duckett fell for 83, gloving a short one from Hazlewood to Alex Carey behind the stumps: 177 for five. This brought in Jonny Bairstow, the last recognised batsman, to join Stokes.

Bairstow started positively but was soon out in unusual circumstances. Having ducked under the last ball of Green’s over, he wandered down the pitch to talk to Stokes and Carey threw down the stumps: Bairstow stumped Carey bowled Green 10.

I will deal with the ramifications of this event in a separate post. All that need be said now is first , that there is no doubt that Bairstow was out according to the Laws of cricket, and , secondly, that the incident had a momentous impact on the course of the day.

The effect of Bairstow’s dismissal on the field of play was almost immediate. Stokes was now joined by Stuart Broad, the first of four tail-enders, all of whom could have vied for the number ten position, if not eleven. Stokes was transformed. He had been no slouch beforehand but he now became truly breathtaking. When Bairstow was out, Stokes had made 62 off 126 balls; he finished with 155 off 214 balls, with nine sixes and nine fours, most of them hooked or pulled with thrilling force to or over the boundary at the Mound Stand or the Tavern. As in his famous match-winning innings against Australia at Headingley in 2019, the power and accuracy of his hitting and his mastery of the match situation, and his manipulation of the strike, were phenomenal. He seemed to be – he was – in utter command; for that hour or so it really was all about him, in a way which is unusual in a game involving thirteen on-field individuals. In both innings he was the only England batter capable of reading and responding to the match situation. Those lucky enough to be present saw one of Test cricket’s outstanding performances.

Nor should Broad’s contribution be underestimated. Like Stokes he was confronted with relentless short-pitched bowling and both men were hit repeatedly (as were Josh Tongue and James Anderson); Stokes and Broad put on 108 (Broad 11).

When the 300 came up it really looked as though England might win. It didn’t happen of course. Hazlewood got Stokes in the end, caught behind aiming a big hit at the longer boundary towards the Grandstand. The difference between Headingley 2019 and Lord’s 2023 was that Australia remained composed. They must have been worried, but they didn’t panic. That must be down to the captain, Cummins. He took three second innings wickets, including Root and Brook, and remained calm during the Stokes assault.

Australia won by 43 runs, which is close but not super close. It could have been much closer. One of the most extraordinary sights of this fantastic match came at the fall of the ninth wicket in Australia’s second innings on Saturday afternoon. It was the sight of Lyon coming out to bat. He had been seen earlier in the day using crutches. Even Starc, the not out batter, seemed astonished to see him. They put on 15 for the last wicket. Interviewed after the match, Cummins said Lyon had been desperate to get out there, but clearly the Aussie brains trust felt they needed all the runs they could get.

Even more significantly, England conceded 74 extras, including 27 byes and 18 no-balls. Australia conceded 39, with just 9 byes.

The two sides are well matched, but on the evidence of Lord’s, Australia are stronger, at least in bowling. England make things harder for themselves than they need to be, illustrated by that annoying batting display on Thursday afternoon. England’s bowlers need to work really hard to get 20 wickets – and dropped catches don’t help; Australia’s are presented with too many gifts. The fact is, though, that England could have been two-nil up; they are instead two-nil down, because Australia, and Cummins, are ruthless at winning the critical moments.

The game featured an extraordinary amount of short-pitched bowling, from both sides. Australia’s was faster, and more challenging; Brook got something of a working over on Friday morning. The tactic seemed to work even for England but it hardly made for entertainment. Walking round the ground after lunch on Saturday, when Green and Carey were batting, Lord’s was strangely quiet. People were just bored with the cricket.

But it was a memorable game in so many ways. After the first over on Wednesday morning two demonstrators got on to the field; one of them was apprehended and carried off the field by Bairstow. A friend immediately texted “Ben Foakes would never have carried off a demonstrator”. Others, more cruelly, remarked that at least he had caught something.

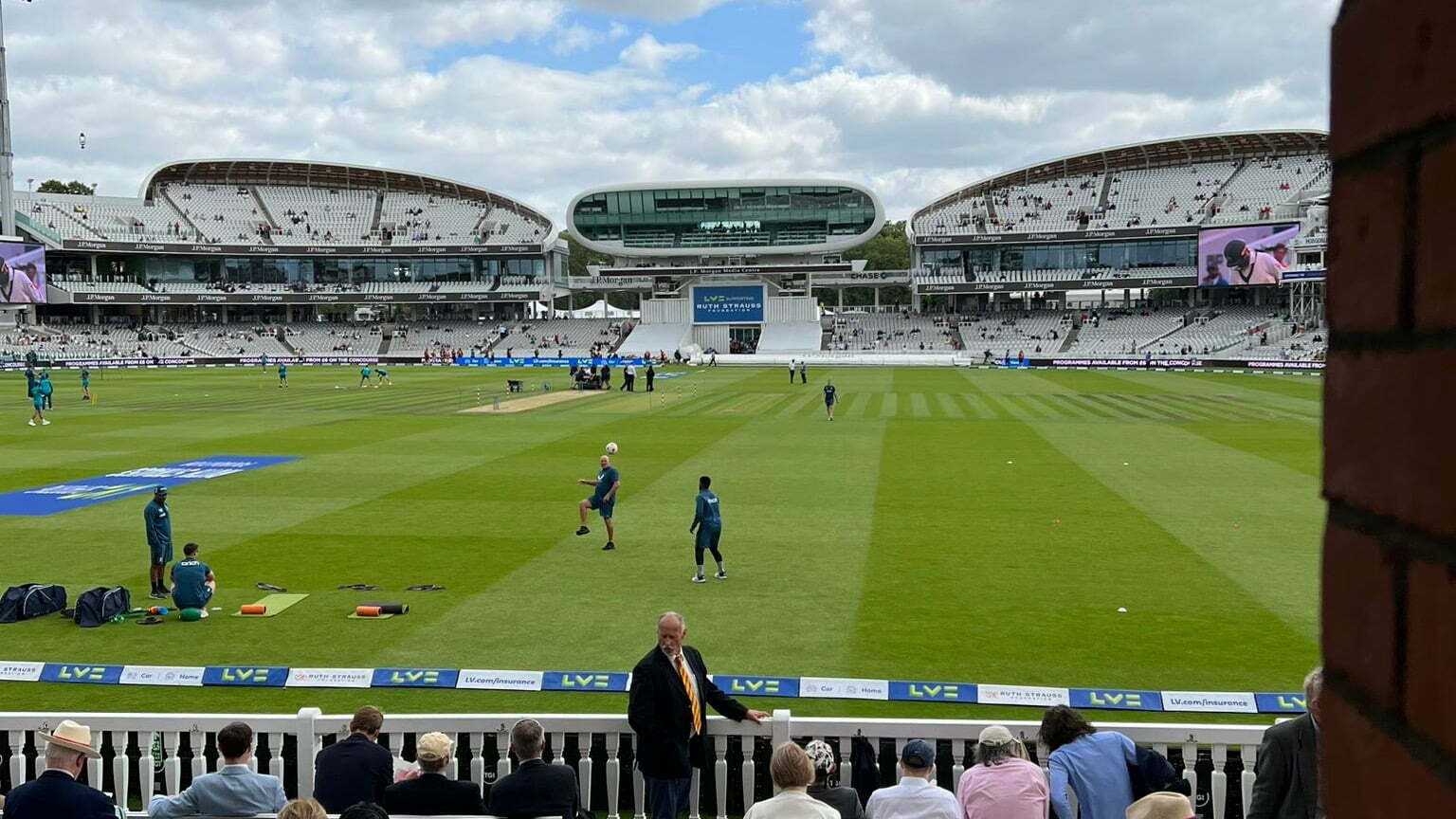

Then it rained. I was sitting outside, in the Lower Allen Stand. You hardly felt a drop but off they all trooped. If this is the standard adopted by the umpires, one felt, we will be lucky to get much play. But the weather played ball for the rest of the match, though the lights were on for the whole of the first day.

Tongue was the best of a slightly lacklustre England attack. The highlight of the Australian first innings was of course Smith’s hundred. He may not have Root’s style or Stokes’ power, but Smith is exceptional. He is weird but compelling, and arguably Test cricket’s greatest batter after Don Bradman. As with Stokes, it was a privilege to be there to watch him.

Sunday, the fifth day , saw the game’s extraordinary climax. It also saw, however, the heated response to what was in many ways, the critical moment of the entire match, the dismissal of Bairstow. That will be the subject of a second post.