Dilip Doshi passed away on 23 June 2025. This is a chapter from my book, The Indian Masters.

Dilip Doshi was an unlucky cricketer.

Discuss

Well surely he was. He was an extremely good slow left arm spinner who happened to come to maturity as a cricketer when India had not just one, not two, not even three but four slow bowlers of Test match quality. Then at last, in 1979-80, by which time he was 32, he got his chance and seized it. He did everything he was asked to do for three years, and took over a hundred Test wickets; then had one unproductive series and was out more or less for good. Trying to practice his craft in England like so many overseas professionals in the 1970s and 1980s, he, found himself beset at every turn by the changing qualification rules and the quixotic desires of county committees. In 1981 he was one of two bowlers to take a hundred wickets in the English season. He was allowed one more year, and that was it.

So, was he unlucky? Maybe, but maybe not. Perhaps, in fact he was lucky to get the chance to play all those Tests, 33 of them, most of them pretty well in a row, between September 1979 and September 1983. Luck, after all, is a curious thing in cricket.

People used to say that Ian Botham was lucky because he got so many wickets with bad balls. A similar thing seems to be implied when it is pointed out, with much head-shaking and tut-tutting, that Shane Warne dismisses lots of batsmen with balls that break neither to the leg nor the off and which are not flippers or top-spinners but which are, in fact, simply plain, straight balls. Luck, of course, has nothing to do with it, except in the sense that Botham and Warne are the sort of individuals who “make their own luck”. There is nothing accidental about it. For both of them it is or was a psychological thing: an aspect, like sledging, of what Steve Waugh called “mental disintegration”.

The Trinidadian Andy Ganteaume made his debut for the West Indies against England in 1947-48 and scored a hundred in his only innings in the second Test at Port of Spain. He was never picked again. Was he lucky to have been picked in the first place or was he unlucky to have been so precipitately discarded? Probably a bit of both. The fact that, as much as ten years later he toured England with an unsuccessful side and did not get a Test offers ammunition for both sides of the argument. The Hampshire all-rounder Trevor Jesty would unquestionably certainly sympathise Jesty was a cricketer of considerable natural gifts who almost from the start of his county career seemed destined for higher things. He was a glorious strokeplayer who developed into a reliable run-scorer, and a very useful medium pace bowler. But the call never came and an air of disgruntlement and lack of fulfillment descended upon him.

Mark Benson, the left-handed opening batsman from Kent, did get the call. He played one Test, against India at Edgbaston in 1986 scoring 21 and 30. That was it for him. Afterwards, Benson said he would have been better off if he had bagged a pair: then nobody would have had any idea how good he was. A couple of scratchy twenties provided more information then was strictly necessary. Graeme Fowler, one year Benson’s senior was another left-handed opener for England. He played twenty one Tests, and in the twentieth, against India at Madras in 1984-85, he scored 201 and helped England win the match and the series. Then Graham Gooch and the other South African rebels became eligible for England again, and for Fowler, it was thank you and goodbye. He was 27 when he scored his double century.

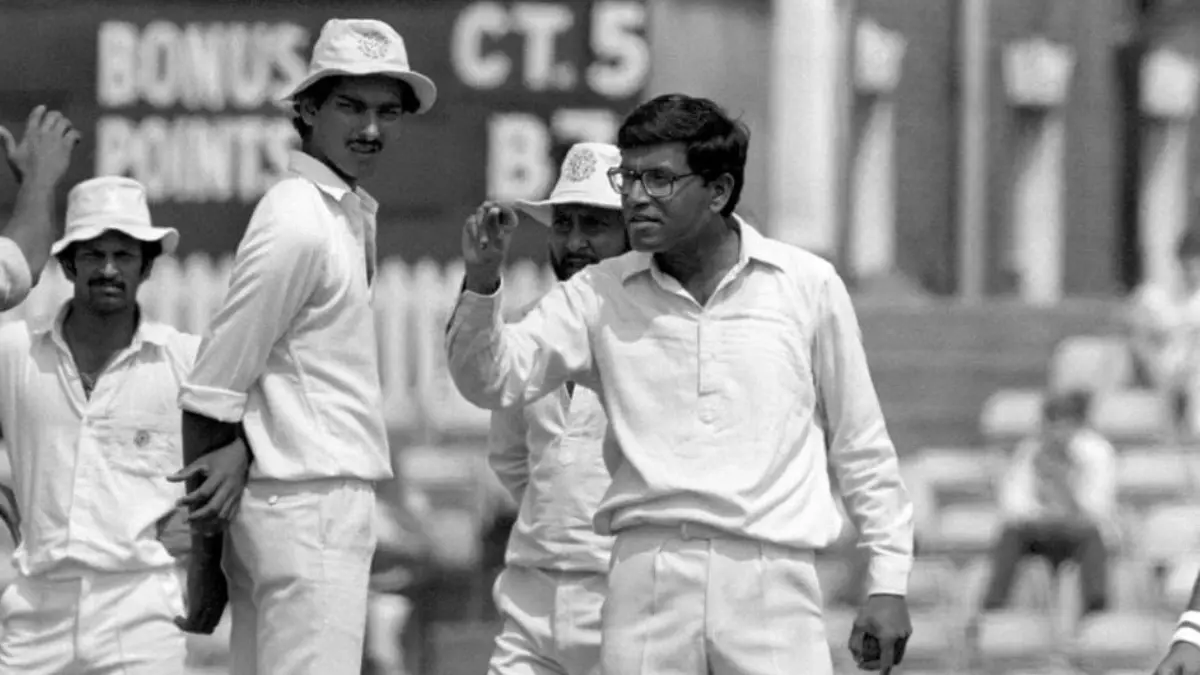

Doshi is probably a philosophical sort of man who takes life’s vicissitudes in his stride. That is certainly the impression that he gave. He is a follower of the Jain religion, a teetotaler and a vegetarian – not exactly a natural for the county circuit of the 1970s. He looked as if he was lucky to be a professional sportsman at all. Mihir Bose said that nobody looked less like a cricketer, resembling more an executive who had temporarily mislaid his briefcase. (He is, in fact, a highly successful businessman.) He was certainly the most heavily bespectacled – in terms of frame if not of lens – cricketer of modern times. Glasses – apart from “shades” of at least partly cosmetic value that are greatly favoured – are becoming very rare. Roy Marshall, one of the most glorious batsmen in county cricket in the 1950s and the 1960s always wore glasses. So did his contemporary the England captain Mike Smith and his namesake the Middlesex opener. These days there is only the New Zealander, Daniel Vettori to carry the torch; and, as we all know, slow left armers are characters. And Doshi, said Bose, was the most remarkable character to play cricket for any country.

Doshi was born in Rajkot in Bengal in 1947. He was educated at Calcutta University and made his debut for Bengal in the East Zone of the Ranji Trophy in 1968-69. In that first year, playing against Bihar he took three for 11 and three for 65 and he bettered that with six for 19 against Assam. Bengal won both games. In the semi-final at Bangalore, Mysore were swept aside by 115 runs, Doshi taking four for 56 and five for 26. But he could not prevent Bombay from winning their eleventh successive title. Doshi took three wickets in the first innings of the final but Ajit Wadekar scored a hundred and Bombay won by seven wickets.

There were some more solid performances in 1969-70 and he earned some national recognition when he was selected for the Indian Control Board President’s XI against the touring New Zealanders in October 1969. Playing for East Zone against the Australians two months later, he took 4 for 38 in 37 overs in the Australians’ first innings and three for 27 in eleven overs in the second, dismissing Bill Lawry twice in the match. The following year he took seven for 29 and four for 30 for Bengal in an innings victory over Assam. In 1971-72 he again played a leading part in getting Bengal to the final of the Ranji Trophy; again Bombay won with some ease.

But however well Doshi performed in domestic and representative matches, he was unlikely to be invited to the top table. The obstacle was Bishan Bedi, only sixteen months older than Doshi and one of the best bowlers of his type, if not the best, in the world. Even so, K.N. Prabhu, writing in 1971, said that there was no spin bowler of Doshi’s calibre playing in English cricket.

Determined to become a professional cricketer, Doshi tried his luck in England. In 1972, he played for Sussex Second XI taking 55 wickets at 19:52: nobody else managed more than fourteen. The following summer saw him achieve the unusual statistical feat of being simultaneously second in Lancashire Second XI’s bowling averages and first in Nottinghamshire Second XI’s. For the latter he took 28 wickets at 11.92. He appeared for the county against the West Indian tourists. He remained on the Nottinghamshire staff for another year without accomplishing anything of note and was released at the end of 1974.

It was two years later that Dilip Doshi first became a name to the mainstream English cricketing public. By this time he was professional for Egerton in the Bolton League and also playing for Hertfordshire in the Minor Counties Championship. The county came second in the Championship, with Doshi taking 32 wickets at 20.85. In the second round of the Gillette Cup they beat Essex at Hitchin, with Doshi, Man of the Match, taking four for 38, his victims incuding Ken McEwan and Graham Gooch. Hertfordshire became the first minor county to reach the quarter-final stage of the competition.

This seemed to reignito Nottinghamshire’s interest and Doshi played a full season for them in 1977, taking 82 first-class wickets at 29.78. He bowled 950 overs, more than anybody else in the country, Wisden remarked that he ended the season more of a craftsman than he started. The county, though, had a disastrous season, finishing bottom of the table 1978 saw a dramatic rise in the county’s fortunes despite a troubled beginning when their best player, Clive Rice, was removed from the captaincy because of his involvement with World Series Cricket. Rice remained as combative a player as ever and his efforts were augmented by those of the new overseas signing, the New Zealand all-rounder Richard Hadlee. The county came seventh in the table, and the foundations were being laid for the successes of the 1980s.

But none of this was very good news for Doshi. A side could not field more than two overseas players in a Championship match and when Rice and Hadlee were available they were obviously going to play. Rice was a South African and therefore available all the time. Hadlee missed the second half of the 1978 season because New Zealand were touring, Doshi played twelve Championship matches and took 49 wickets at 30.16, including six for 73 against Leicestershire at Trent Bridge. But it was obvious which way the wind was blowing and at the end of the season the county released him for a second time. 1979 saw him turning out as professional, for Northumberland. The county drew all twelve of their games in the Minor Counties Championship. Doshi took 53 wickets at 21.09.

But on the international scene, things were looking promising. India toured England in 1979 and lost a four-match series one-nil. The series marked the end of an era. Of the four great spinners, Prasanna had played his last Test in the previous series in Pakistan; against England. Bedi took seven wickets at 35, Venkataraghavan six at 57, and Chandrasekhar nought for 115. At the start of the next home series, against Australia in 1979-80, the spin attack was being led by Dilip Doshi.

So by the time he became a Test cricketer Doshi was unusually experienced for a non-English player. He had played well over a hundred first-class matches and taken more than five hundred wickets. He had played on all sorts of different surfaces, in England and in India. While not being quite in Bedi’s class – Christopher Martin-Jenkins, writing about his peformance for East Zone against the touring MCC side in 1976-77 said that, on that occasion at least his bowling was too flat and too wide to be a threat to the best players – he had developed into an extremely capable exponent of the slow left armer’s art. He was tireless and accurate and gave the ball a considerable tweak. As the years went on he became better and was arguably the world’s leading spin bowler by 1981-82. Like Bedi, Chandra and Prasanna, he was a specialist. “Nobody on the planet”, said Scyld Berry “except himself takes Doshi’s batting seriously”. And his fielding was of the same ilk.

Doshi was never likely to let this opportunity at the highest level pass him by. The Australians, playing their last series before the post-Packer reunification, were a largely inexperienced side, although Kim Hughes, the captain, and Allan Border, were to come of age as Test cricketers in the series, both averaging over fifty. India won the six-Test series two-nil.

Doshi showed what he was capable of in the first, drawn, Test at Madras, which started on 11 September 1979, the earliest date on which Test cricket had been played in India: the Test against England at The Oval had only finished a week before. In Australia’s first innings he took six for 103 in 43 overs, as Australia slumped from 318 for 3 to 390 all out. India won the Third Test at Kanpur and the sixth at Bombay and Doshi played a key role in the latter match. India batted first and made 458 for 8, Sunil Gavaskar and Syed Kirmani making hundreds, Doshi’s fingers must been itching as he sat watching Border take the wickets of Gavaskar and Dilip Vengsarkar with his left arm spin. Sure enough Doshi troubled all the batsmen in Australia’s first innings, claiming five for 43 in 19.5 overs. Resistance was scarcely more effective when the visitors followed on. Kapil Dev and Doshi demolished the batting, the latter claiming three for 60. Doshi bowled more overs than anybody else in the series and finished with 27 wickets at 23.33.

Now he was back in county cricket, this time for Warwickshire. He signed for the county shortly before the 1980 season started and helped them win their first Championship game of the season by taking four for 36 in Hampshire’s second innings. Three weeks later the county beat Worcestershire by seven wickets, Doshi taking four for 59 in the home side’s second innings. They did not win again until the last game of the season, at Taunton, when Doshi took five for 95 and six for 72: Warwickshire won by ten wickets and finished fourteenth in the table. Doshi finished the season with 101 first-class wickets at 27.61.

He had a reasonably successful tour of Australia in 1980-81 and performed heroically in the Third Test at Melbourne. He did not realise it at the time but he went into the game with a broken bone in his left foot, having been struck on the instep while batting in the game against Victoria. He still bowled 52 overs in Australia’s first innings. In the second innings, as Australia chased 143 to win, he bowled in what Wisden called “great distress” in support of Kapil Dev, also suffering from injury. Doshi captured the critical wickets of Hughes and Graeme Wood and India won by 59 runs. He missed the first Test against New Zealand that followed. In the third, at Auckland, he had remarkable first innings figures of 69-34-79-2. It was in this series that Ravi Shastri made what D J Rutnagur called his “fairytale” Test debut as a left-arm spinner.

Warwickshire had an even worse season in 1981 than in 1980, finishing bottom in the Championship for the first time since 1919 and winning only two games. Doshi, of course, bowled more overs than anyone else but his 42 Championship wickets cost 44 runs apiece. Even so, one would have thought that the position of the one quality spinner in a side full of seamers would have been safe. But new rules governing overseas players were being introduced for the 1982 season and Doshi was a victim because his Warwickshire contract had started after 1978. This time his county career really was over.

But his Test career was about to enter into its most successful phase. Along with Kapil Dev he was the outstanding bowler of the series when India played England in 1981-82, taking 22 wickets at an average of 21.27: needless to say he bowled more overs than anyone else. He also bowled the single most decisive spell of the entire series; in England’s first innings in the first Test at Bombay. India batted first and made 179, Ian Botham and Graham Dilley each taking four wickets. Graham Gooch was out early, but Geoffrey Boycott and Chris Tavare added 92 in 58 overs (does it not set the pulse racing just to think about it?). Then the visitors slumped from 131 for 3 just before tea on the second day to 166 all out. Doshi, with, it has to be said, some assistance from the umpires, took four wickets in five overs for nine runs. He finished with five for 39 in 29.1 overs. His batting, for once, played a part too, when he helped Madan Lal put on 24 for the last wicket in India’s second innings. India went on to win the match and the series. All the remaining matches were drawn. Doshi’s controlled, accurate and testing left arm spin, often bowled from over the wicket was an important factor in what was essentially an attritional struggle. Only in the second Test at Bangalore, when he suffered from a viral infection, was he less than fully effective, usually conceding fewer than two runs an over. In the fifth Test at Madras he took four for 69 in England’s only innings and in the sixth Test at Kanpur he took four for 81.

If Doshi was the bowler of the series, one of the batsmen was undoubtedly Botham who batted magnificently throughout and scored 440 runs at an average of 55. Scyld Berry remarked on the almost comical contrast between the ragged athlete Botham and the reflective, almost ascetic Doshi. Botham launched some blistering assaults on the spinner, but honours ended up pretty even; Doshi dismissed him four times in seven innings.

All the while he remained a leading figure in domestic cricket captaining Bengal for six years from 1978-79. He took 63 first-class wickets in all in 1981-82 at 22.26. Bowling for the East Zone in the final of the Duleep Trophy against the West Zone in Bombay he literally bowled all day – 51 overs, missing one while he changed ends, out of 73 in all.

He was back in England anyway in 1982, playing for India. England won the Test series one-nil. Again Doshi bowled more overs than anyone else and only Bob Willis took more than his 13 wickets. In the second Test at Old Trafford he took six for 102: Wisden said he bowled “superbly” on the first day when he dismissed Geoff Cook, Chris Tavare and Derek Randall cheaply. In the final Test at The Oval he bore the brunt of another powerful assault from Botham. The all rounder made a rapid double century, but Doshi got him in the end, claiming four for 175 in 46 overs.

In September 1982, he played in the inaugural Test between India and Sri Lanka at Madras, a high-scoring draw. Doshi destroyed Sir Lanka’s middle order in their first innings in which he took five for 85: Arjuna Ranatunga was his hundredth Test victim.

India then toured Pakistan in what turned out to be a rather traumatic experience for the visitors. Pakistan won the six Test series three-nil and their batsmen scored mountains of runs. In the first Test at Lahore, which was drawn, Doshi took five for 90 in Pakistan’s first innings, but his figures for the series – eight wickets at 61 apiece – told a sorry tale, and he was dropped for the last two games.

He missed the tour of the Caribbean in the spring of 1983 and played once more, against Pakistan at Bangalore in 1983-84 taking one for 52 in Pakistan’s only innings. He was then 36. He retired from first-class cricket at the end of the 1985-86 domestic season. His son, Nayan, put in some promising performances for Surrey in 2004, both in the Championship and in that most un-Doshi-like competition, the Twenty 20.