Two events in the last few weeks, the heroics of Ashton Agar at the first Ashes Test at Trent Bridge, and the retirement of the New Zealand seam bowler Chris Martin, prompt thoughts abut the vagaries of batting at number 11.

Agar and Martin are polar opposites on this issue. Agar was making his Test debut at Trent Bridge and second 98 in a breathtaking display of free-flowing drivers: Geoff Boycott compared his style to that of Gary Sobers. Martin, a fine opening bowler who took 233 Test wickets, finished his career with a batting average of 2.36 and 36 ducks.

Cricket is unusual in that while it calls for a wide variety of specialist skills, everybody has to bat. This obliges participants, at the professional and international level, to put on a public display of something at which they are not particularly good, or may indeed ,as with Martin, be conspicuously inept.

In a recent article in The Cricketer magazine Andrew Miller demonstrated Martin’s unchallenged status as the worst number eleven of modern times. These days everybody has to bat a bit. James Pattinson, who replaced Agar as Australia’s number eleven, looked to be one of the side’s more accomplished batsmen.

Martin has some historical challengers though. Bert Ironmonger, the Australian slow – medium off-spinner who made his debut at the age of 46 against England side in 1928-29 had a Test batting average of 2.62. It is said that, as he walked out to bat at his home ground, the MCG, the dray horse that pulled the heavy roller between innings, used to move into position between the shafts. Once, his wife called the dressing room phone, “Bert’s just gone out to bat” she was told. “I’ll hang on”, she said. Jack Iverson, Australia’s mystery spinner in 1950 -51, averaged less than one in his brief Test career.

Below Test level, the Northamptonshire seamer Jim Griffiths attained legendary status as a tail ender, making ten consecutive scoreless innings at one stage in his career but finishing with a relatively stellar average of 3.3. As is bound to be the case with lower order batsmen there were a lot of “not outs”: Martin was not dismissed in 52 of his 104 Test innings so that his “proper” average was not much more than one.

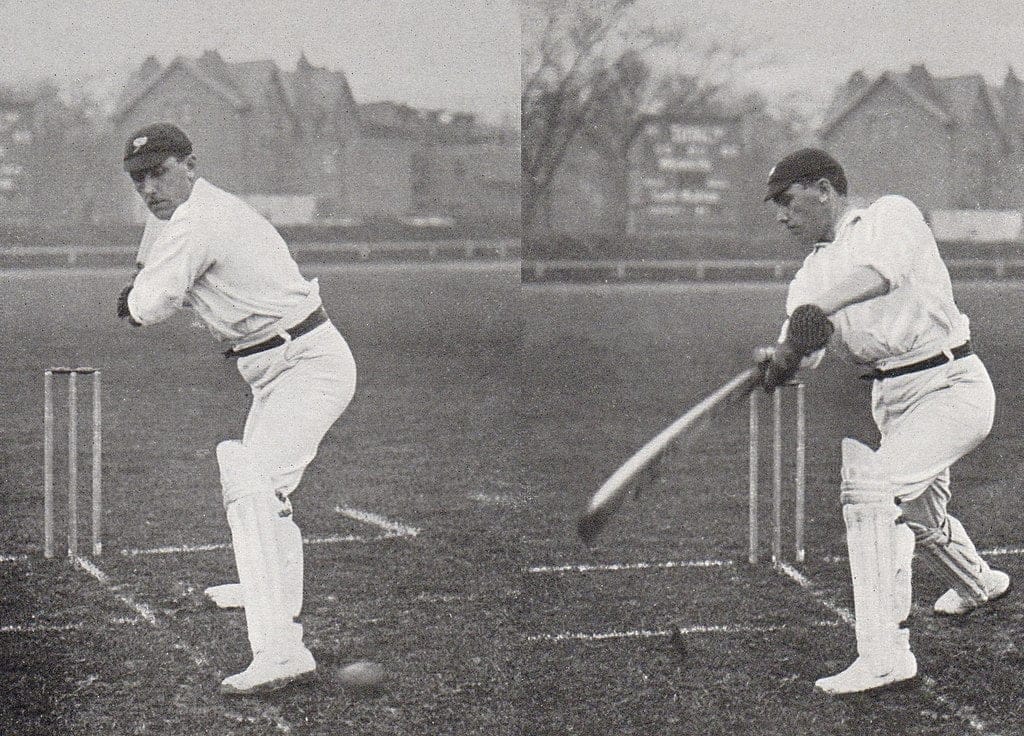

A more promising example for Agar might be the great Yorkshireman Wilfred Rhodes, also a slow left armer, but a right handed batsman. Rhodes made his debut at the age of 22 for England against Australia at Trent Bridge in 1899, in what turned out to be W G Grace’s last Test match. He batted at number ten in that match but his customary partition for the next few years was eleven from where he took part in two of Test cricket’s most famous partnerships. The first was in one of the great Ashes series, in 1902, when in the final Test at The Oval with his fellow Yorkshireman George Hirst, (also a left arm bowler and right handed batsman) he put on 15 for the last wicket to guide England to a one-wicket victory, a stand immortalised by Hirst’s reported advice to his junior partner that “we’ll get ‘em in singles”. In the first Test of the next Ashes series at Sydney in 1903-04, Rhodes helped R E Foster (287, still the highest score by an Englishman in Australia ) put on 130 for the last wicket in an hour; Rhodes made 40 not out. That remains England’s record partnership for the tenth wicket. England won the series, having lost four Ashes series on the trot, and Rhodes took 31 wickets at fifteen apiece.

By the next time he toured Australia in 1911-12, Rhodes was opening the batting with Jack Hobbs . In the third Test at Melbourne they put on 323 for the first wicket which was the English record until 1948-49 (it is still the England record for an Ashes Test ). Rhodes made 179. In that series he bowled just 10 overs.

Of course it is inconceivable that a career like Rhodes’s could be replicated in modern times . It will be interesting to see how Agar develops. At nineteen he is clearly too young to be leading a Test spin attack but he has plenty of time to develop as both a bowler and a batsman. The principal obstacle to his progress is that he is a member of such an under-performing team. Australia needs a Simpson-Border style assessment of character and technique – but especially character – to be able to rebuild from the wreckage of 2013.

Bill Ricquier, 10/08/2013

This article was published in The Island: http://www.island.lk/index.php?page_cat=article-details&page=article-details&code_title=85568

Featured image: Ashton Agar Bowling. Image by Nic Redhead from Birmingham, UK (Ashton Agar) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons