There are many worse places than Singapore to be a cricket person. You can play; there are some local leagues. You can hobnob with a senior administrator: Imran Khwaja, a friend and former colleague of mine, is a board member of the International Cricket Council, and a former vice-chairman. The Singapore Cricket Club is a historic institution with a fabulous location in the heart of the city. The game is rarely played on the Padang these days, but the Club recently hosted an evening with Henry Blofeld. I was lucky enough to sit next to him at dinner; he was utterly charming and hugely interesting. The talk was entertaining and apparently effortlessly delivered.

Watching live international cricket is obviously the main concern because it involves so much travel and expense. In fairness there is a lot of live cricket on a couple of designated satellite TV channels. The feed comes from India and there is a lot of mindless repetition of celebrated Indian victories. And if I have to watch that interview with Virat Kohli in his tuxedo at The Honourable Artillery Company ground one more time…

It means also that cricket talk is less common than it would be in, say, London or Melbourne, or Mumbai; obviously you don’t get to meet Henry Blofeld every day.

We had a dinner party recently with a mixed group of friends, some Singaporean, some expatriate. I have to confess that the subject of cricket may have incidentally cropped up. (It is an observation I do just occasionally make – but nobody seems to believe me – that (almost) whatever you are talking about, there is a useful or apposite contribution to be made from the world of cricket.)

Anyway, one of our guests – Rachel, a Singaporean lawyer who grew up and studied in Australia – suddenly said “Oh, I had lunch with an old cricketer called Don Bradman a couple of times.”

Well, you could have knocked me down with the proverbial feather. It turned out that Rachel had been an intern at a firm in Canberra. One of the partners she worked for was an old friend of Bradman’s and they would have lunch if the great man was in town.

I am not quite sure whether Rachel was entirely aware of the significance of this – to me – extraordinary revelation. She is not a cricket person in any real sense but, no doubt because of her upbringing Down Under, she knew enough to realise that Bradman was, well, sort of famous.

Strangely enough, just a few days earlier we had been guests at a party in a seafood restaurant hosted by a Singaporean friend of ours; Noor is half Malay and half Polish – even I have struggled to rouse her curiosity about the great game. But the purpose of the dinner was to welcome home her son, who is studying in Sydney. His Australian girlfriend and her family were also there.

I was sitting next to the girlfriend’s father. “Where do you live?” I asked. “A place called Bowral” he said.

Again, this time perhaps with less justification, I was startled. Less justification because, after all, probably quite a lot of people must live in Bowral.

Quite a few of the people reading this will be aware of the fact that Don Bradman was born and grew up in this little town in the New South Wales outback. There is the legend of the solitary boy honing his skills as a batsman by throwing a golf ball against a brick wall and playing the rebound with a stump; that happened in Bowral. It is now a more developed place with a beautiful ground, the Bradman Oval, and a highly regarded Bradman museum.

So, for a certain type of cricket nerd Bowral is like – well, where -? Bethlehem? Stratford-upon-Avon? Woodstock? It’s really famous. Because of Don Bradman.

Does one have to be slightly deranged to find these two small dinner party exchanges interesting? I don’t think so. The truth is that most people are fascinated by fame.

Jack Ingham, the Australian racehorse magnate once said that “[i]t is strange, but I think true, that all the time, day and night, somewhere in the world someone is talking about Bradman.” This is surely borne out by my little encounters. It is a truism that life changes for even moderately successful sportsmen quite early on. But for someone like Bradman we are operating on a different level.

Judging the merit, quality or worth of a sportsman must always involve an element of subjectivity. But cricket is different from most other sports, apart from baseball, because of the availability of meaningful and comprehensible numbers to help assess the performances, in a given match, or series, or season, or across an entire career. By this purely numerical yardstick, Bradman was incomparably the best batsman of all time. Put simply, he averaged 99 in Test cricket. No one else, before, during or after his time, has averaged more than 65.

He was a phenomenon. People turned up in their thousands to watch him play and would leave the ground when he was out. More than that, when New South Wales travelled by train to play, say, Queensland in Brisbane, people would flock to the country railway stations, just to get a glimpse of him.

That’s fame. That’s why I was intrigued by Rachel’s story. Bradman retired in 1948. I have known many people who saw him play. But I had never net anyone who had had lunch with him, except at a formal cricket event with lots of other people present. Of course, Sir Donald (he was knighted by George VI in 1948) was famous for playing cricket, he wasn’t famous for having lunch (unlike, say, Mike Gatting, a legendary trencherman). But that’s the point. It would have been ungallant to probe Rachel as to precisely when these lunches took place. Bradman died in 2001 at the age of 92. But for the true believer the very idea of meeting this little, old, retired stockbroker has tremendous resonance.

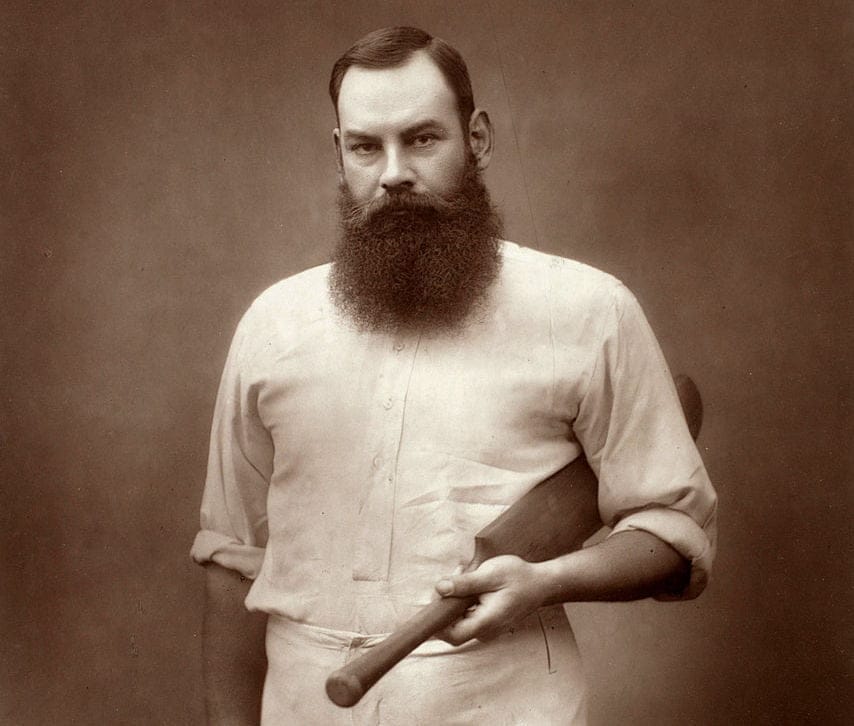

Simon Barnes once wrote that cricket had three iconic figures: Bradman, Sachin Tendulkar, and W G Grace.

With Tendulkar, the Bradman parallels are obvious. The Don commented on aspects of Tendulkar’s batting which reminded him of himself. But that is not what we are talking about here. It is Tendulkar’s almost literally divine status in India. A more apposite point is a story told to me by an architect friend in Singapore. He worked sometimes with an Indian architect based in Mumbai. That architect’s firm designed Tendulkar’s house. Once, and once only, The Little Master (like Bradman, Tendulkar was not an imposing physical presence) came to the architect’s office in downtown Mumbai. By the time the brief meeting was over, the streets outside the office were impassable. Again, that’s fame.

With Grace, it is different for the simple reason that it was a different world. Bradman’s superlative numbers notwithstanding, it is difficult to argue with the verdict of the simple inscription carved on the central pillar of the ceremonial main entrance to Lord’s, the home of cricket, the Grace Gates: The Great Cricketer.

In a recent episode of the talkSPORT’s “Following On” podcast, Jarrod Kimber and John Northam had a fascinating discussion about Grace. His numbers, too, were off the scale, especially when compared with his contemporaries. He effectively invented modern batting and took thousands of wickets as well as making tens of thousands of runs and breaking every record going. An (unpaid) amateur he probably made more money out of the game than anyone before the IPL millionaires. He travelled the world playing cricket, breaking all the rules wherever he went. Unlike Bradman and Tendulkar he was instantly recognisable, big and tall with a long black beard. And although the conventional history books ignore him, this magnificent if rather terrible figure was almost certainly the most famous man in Victorian England. As Kimber said, W G was the first international sportsman.

The podcast was recorded in dull, suburban Beckenham. Why? W G Grace was buried there.

I am prepared to admit, I suppose, that other sports can produce similar iconic figures. This is perhaps easier to establish in individual sports. Muhammad Ali is the classic example. Another is the great American golfer, Arnold Palmer. Now we are entering the realm of the agent, first epitomised by Mark McCormack’s IMG group. Tendulkar had a highly effective and influential manager, Mark Mascarenhas. Now even the average county player will have an agent.

Television has been a huge influence, not just in sport but entertainment generally. That is the extraordinary thing about Grace, that he could become a world famous figure without the benefit of this medium we take so for granted.

Of all the things the cloth-eared administrators of the England and Wales Cricket Board have done in their avowed intent to ruin the English game, none has done more lasting damage than the decision in 2005 to remove cricket from terrestrial television. We all grew up to the dulcet tones of Peter West; he was part of the furniture. I have so many friends back in England who simply don’t engage with cricket anymore.

In 1975, the grey-haired Northamptonshire batsman David Steele – “the bank clerk who went to war” – was voted BBC Sports Personality of The Year, because of his heroic batting against Australia ‘s Jeff Thomson and Denis Lillee. Will we ever see another cricketer in that role? It doesn’t seem likely.

But of course lack of exposure on free-to-air TV doesn’t equal anonymity, not in the 21st century. You might think you’re pretty well on your own in a side street in Bristol at 4 o’clock in the morning. But in September 2017 Ben Stokes found himself in the company not just of fellow night-club denizens, but also the inevitable bystander with a mobile phone. Notwithstanding his acquittal, Stokes will be paying the price for those few seconds of video footage for a long-time.

The cult of the “celebrity” is another modern development. This is a frequently misused word; it seems to me. Half listening the other day to the mindless twaddle that constitutes breakfast radio in Singapore, I heard someone talking about an event – I have no idea what it was – in which various “celebrities” participated. One of them was mentioned by name: Hugh Jackman.

That is surely not right. It is true that Jackman is the sort of person who is likely to be instantly recognisable all over the world. Admittedly, I might struggle to recognise him myself but that is nothing to do with him; my eyesight means I often struggle to recognise people I know very well until I’ve virtually bumped into them. But Hugh Jackman is not a celebrity. He is a distinguished stage and screen performer who has earned his fame by working for it.

Can you morph into being a celebrity after having been genuinely famous? Maybe. I do not know or care enough about football to be able to say whether David Beckham was a great player. My hunch is that he was a very good player capable of occasional moments of greatness. But he was famous all right and since retiring from football he has become even more famous. He has become, in fact, famous for being famous: Beckham is a celebrity.

One fears that something similar might happen to Shane Warne. Unquestionably, with Gary Sobers, the greatest cricketer since World War Two, he always had “issues” off the field. Now he is off the field permanently, he faces the same sort of problems that confront all retired sportsmen, famous or otherwise. I love his commentary on the whole, but it is not perfect. One senses a growing danger of becoming a parody of himself.

Beckham and Warne both wanted to be famous. Nothing wrong with that. We are all obsessed with it to one degree or another. But it can be something like an addiction, a curse, a disease, maybe incurable. Andy Warhol was of course absolutely right: “In the future everyone will be world famous for fifteen minutes.” We are not talking about sportspeople here. This is TV talent show contestants and all the rest of it. The process predicted by Warhol reached its apotheosis with the election of a reality TV host to the leadership of the free world. We get the governments we deserve, at least in the so-called democratic West.

And if they’re not all talking about you, well you can talk about them. The growth of social media means that any damn fool with a tablet and half an opinion can inflict it on a defenceless, if indifferent world (yes, guilty as charged). Of course, Donald Trump is hyper-active at both ends of the equation; one day this crass and appalling man could tweet all mankind in to oblivion.

Sportspeople and entertainers are the most obvious examples of global fame. The other obvious case is royalty.

The Queen doesn’t “do” very much – she shakes a lot of hands, declares power stations open, tolerates as house guests grotesques like Robert Mugabe and Nicolae Ceaușescu whom normal people would just tell to push off – but nobody could call her a celebrity. As a British citizen I have no embarrassment at all in being a royalist, although I understand the reservations many friends have. Personally, I can’t imagine a worse system than an elected nominal head of state, a retired bureaucrat, or failed politician (you could hardly have a successful one, even if such an animal existed these days). The Crown gives continuity and a sense of history, not to mention tourist revenue.

It has its own aura and lustre. Not only is the Queen not a celebrity; to call her “famous” seems an insult.

I remember as a little boy – I can’t have been more than five or six – being taken by my mother to the Upper High Street in Winchester to see the Queen being driven to the formal opening of the new and rather ghastly Kremlin-like county council offices. The crowd was, or at least seemed, enormous. Many people have memories like this. They are our Bradman and Tendulkar moments.

Sometimes the aura and the lustre don’t quite work. In his recently published diaries (Who’s In, Who’s Out, 2018) the extremely well-connected journalist Kenneth Rose tells a story about the Queen’s late uncle, the Duke of Gloucester, going to meet ex-King Umberto of Italy on the latter’s arrival in London to attend the funeral of the Duke’s brother, King George VI.

“D of G said to him: “Had much rain in Rome lately?” “Well, as a matter of fact, I don’t live in Rome now.” “Then who the hell are you?””

Bill Ricquier

Credits: The title image “Smiling Study of Don Bradman” is from the collections of the State Library of New South Wales.