How important is captaincy in cricket? is there room in an international eleven for a player who is in the team solely because he is captain?

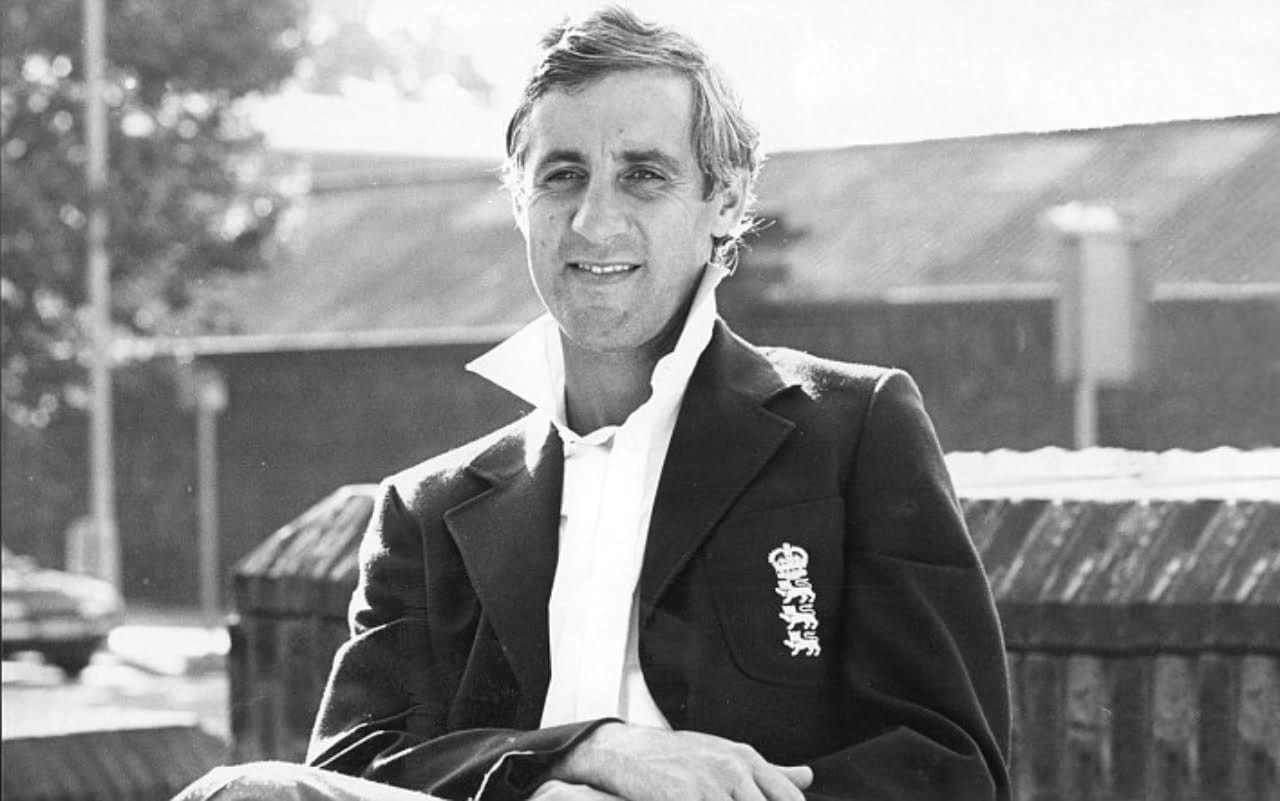

These issues are squarely raised by the cricket career of England’s most successful – in terms of win-to-loss ratio one of the game’s most successful – captains.

Brearley led England in 31 Test, winning 18 and losing four. For Clive Lloyd the figures were 74:36:12. For Steve Waugh they were 57:41:9. Brearley captained in nine series, winning seven, drawing one and losing one.

Timing is everything, and in the timing of his captaincy Brearley was fortunate. He was appointed to lead England in the summer of 1977 after the news broke about the establishment of World Series Cricket by Australian television magnate Kerry Packer. The England captain, the charismatic Tony Greig, was one of Packer’s chief lieutenants, and was immediately removed from the job, Brearley replacing him.

The Australians were the visitors that summer and they were a moody and dispirited lot, lacking many of their Packer players. England were convincing winners, regaining The Ashes that had been ruthlessly wrested from them by Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson in 1974-75 and retained in 1975.

England had lost some big names to Packer – notably Alan Knott and Derek Underwood. But some important senior players remained, in particular the fast bowler Bob Willis and the opening batsman Geoff Boycott, who returned from self-imposed Test exile during that Ashes summer. Obviously, as with all the countries affected by Packer there were opportunities for younger players too; England just happened to produce two of their very best in Ian Botham, who made his debut in 1977 and David Gower, who started a year later, as well as other very good players such as Mike Gatting and Derek Randall.

England were generally more than a match for their opponents over the next couple of years, never more so than in Australia in 1978-79, when Graham Yallop’s disconsolate home side lost 5-1.

The boot was on the other foot a year later when the Packer players returned for a three-match series that was not part of The Ashes. Australia won every game.

Brearley stepped down and the selectors appointed the prince in waiting, Botham.

Botham’s timing was not nearly as good. England’s first engagement was a home series against the West Indies – Andy Roberts, Michael Holding, Colin Croft, Joel Garner, and all the rest of it. England lost, but respectably. Their next engagement was against – well, the West Indies again, in the Caribbean. They lost again.

Next up it was The Ashes again, Kim Hughes bringing a full-strength side, missing only Greg Chappell and Thomson of their leading players. By the end of the second Test at Lord’s, where Botham bagged a pair, Australia were one-nil up and the captaincy experiment was over. Brearley returned for the third Test at Headingley.

It is to a large extent on the basis of the extraordinary events of the next few weeks that Brearley’s reputation as a captain rests. England won the series 3-1. Botham was the outstanding player, producing successive, superhuman, almost magical feats with bat and ball (and not forgetting Willis at Headingley). Brearley himself described Botham as cricket’s greatest matchwinner.

But there can be no doubt that Botham would not have been able to do it without Brearley. Of course Brearley was a much older man – he was 39 by the time of the Headingley Test – but it wasn’t just a matter of experience or even common sense.

It was the Australian fast bowler Rodney Hogg who said that Brearley had a degree in people. That was a beautifully shred comment. Brearley was famously – notoriously – clever in the conventional, academic sense. He got a first in classics at St John’s College Cambridge and came first in the Civil Service entrance exams; he researched at taught philosophy at universities in California a d England. He is not the first, or last, clever cricketer. The current national selector, Ed Smith, is a distinguished author and journalist. But he was a notably unsuccessful captain in county cricket.

Smith, one feels, lacks EQ, or certainly elements of it. In July 1981 no-one knew what EQ was, but Brearley had it in spades. As Hogg recognised people fascinated Brearley. He was able to build up a rapport with every single member of his team. He knew how to gee them up and how to calm them down. There is the famous story of Brearley dubbing Botham the “Sidestep Queen” to get him to bowl with more intent. It worked. Walking out to bat with newcomer Chris Tavaare Brearley started talking to him about zoology, Tavare’s subject as an undergraduate at Oxford, to help him feel relaxed.

The selectors wanted Brearley to carry on after the 1981 Ashes but he had already indicated an unwillingness to tour again; that was why the selectors had picked Botham. While Keith Fletcher was leading England in India in 1981-82, Brearley was embarking in a course in psychotherapy. it is his practice in that field, together with writing, that has occupied his time since retiring from cricket in 1983.

Boycott said that Brearley was the best captain he played under. In fact he went so far as to say he would have had more success in his career if Brearley had captained him more. It makes one wonder how Brearley might have handled someone like Kevin Pietersen. Shane Warne, for one, is certain that England handled Pietersen the wrong way. Brearley has an interesting story about Ray Illingworth when he became captain of Leicestershire (incidentally, he said Illingworth was the shrewdest captain he played against). Within a year of joining the county Illingworth secured the departure of the side’s two leading batsmen, Clive Inman and Peter Marner, “on the grounds that the team would never function as such with them around”. Brearley did not comment on the rightness of the decision but cited it as an example of what might need to be done.

Cricket captains, especially international ones, have such a lot to do. Micro-management on the field is just one part of it. Looking back, the 1970s was a golden age of cricket captaincy – not only Brearley and Illingworth but the underrated Greig. And in those days there were not the serried ranks of support staff that exist today. The responsibilities were extremely challenging. And then there was the day job. As Brearley said in his justly acclaimed book, The Art of Captaincy, the main difference between a cricket captain and a football manager was that the former did not just have to manage; he had to bat and field and in some cases bowl, and his performance in those roles would be judged.

For Brearley, batting was the issue. For someone batting in the top order, often opening, a Test average of 22, with no centuries, just doesn’t cut it. It’s odd; at every level below Test cricket he had an exemplary record. In those years at Cambridge he did not simply acquire academic honours; in four years in the eleven – two as captain – he scored more runs for Cambridge than anybody else, ever. In 1964 he made two thousand runs for Cambridge and Middlesex, earning a place as a spare batsman on MJK Smith’s tour of South Africa. In 19966-67 he captained an MCC Under-25 team to Pakistan, heading the averages and making a first-class triple-century in Peshawar. Incredible though it may seem, he opened the batting in a World Cup final, putting on 129 with Boycott against the West Indies in 1979.

He played no first-class cricket at all in 1968 and 1969 but at the end of the 1970 season was invited to return to Middlesex as captain in place of Peter Parfitt.

This was in some ways an old-fashioned appointment, or rather it looked like one. Parfitt and before him Fred Titmus, two old pros, had been in charge since 1965. in that time the county had finished in the top half of the table only twice. This was even though there was a galaxy of Test players, John Murray, John Price and Eric Russell as well as Titmus (an England regular for years) and Parfitt.

The appointment of Brearley – public school and Cambridge – looks like a throwback to the 1950s. That may well have been how the Middlesex committee regarded it. In fact it turned out to be extraordinarily forward thinking. The old guard moved on (Titmus stayed forever) a d an exceptionally talented group of diverse and character-full cricketers was put together. In 1976 Middlesex won the championship for the first time since 1947. They won it twice more under Brearley, together with some one-day silverware.

And he kept getting runs. He was to finish with over twenty-five thousand at an average of almost 38, which is more than respectable. In 1976 came his first Test call-up, against Lloyd’s West Indians. He was Greig’s vice-captain in India in 1976-77. Then came the drama of the Centenary Test, then, suddenly, Packer, and everything changed.

In some ways, strange as it may seem, it was the series he lost, in Australia in 1979-80, that saw Brearley at his best. It was a challenging series in many ways, and not just because Australia were back at full strength. In some ways it was the first “modern” season as everything seemed designed to suit the new masters, the television moguls (of course we are used to that now). For instance Australia reverted to the six-ball over, for the first time for many years. There was an absurdly complicated schedule involving not just the three Tests but one day games against the West Indies (who also played three Tests against Australia.

The playing conditions for England’s. matches had not been conclusively agreed by the time Brearley’s team landed in Australia and, incredibly, he was required to resolve the outstanding issues with the Australian board. Nearly all the Australian proposals were gimmicks aimed at television and Brearley rejected most of them. He was immediately characterised as a “whingeing Pom” and subjected to boorish abuse for the rest of the tour. He had grown a beard since his last visit and was hilariously nicknamed “the Ayatollah”.

Boycott wrote that he had only twice seen Brearley lose his temper. Once was with the Middlesex and England spinner Phil Edmonds: Brearley had admitted that the relationship with this, one suspects, exceptionally prickly character was a blind spot of his captaincy. The other was with Boycott himself and it happened on that 1979-80 tour.

Just before the second Test at Sydney Boycott had played golf and ricked his neck. He announced that he would not be able to play. Brearley, apparently, completely lost it, shouting and screaming at Boycott at the top of his voice. It was such an unusual occurrence. Curiously enough Boycott ended up playing, which, as he admitted, must say something.

Anyway, as I said, Australia won all three fames comfortably. Brearley put them into bat in the first Test, in Perth, which is a rare event. The game is mainly remembered for Lillee’s tiresome insistence on using an aluminium bat, despite the protests of Brearley and the umpires; more opprobrium for be England captain from the less distinguished members of the Australian cricketing fraternity. And, another rare event, Brearley top scored in England’s first innings, making 64 in over four hours. In the third Test at the MCG he made 60 not out in just under four hours in the first innings.

As his friend John Arlott observed, had he had the good fortune to play as a Test batsman under the captaincy of J M Brearley he might have developed into a pretty good player.

Bill Ricquier