The other day I was leafing, as one does, through the pages of Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack for 2012 when I came across an article that I had somehow missed previously. It was by Jarrod Kimber and had the title ‘Not picking the wrong ‘un’. It is a good piece, recounting the Australian selectors’ impossible task in seeking a replacement for the legendary legspinner. What makes it interesting is Kimber’s focus on the man he describes at the real victim of Warne’s success, a legspinner called Craig Howard. Howard was a team-mate of Warne’s in the Victoria State side of the early 1990s: a good bowler, with a terrific googly: but not as good as the almost freakish Warne. Injury and loss of confidence meant Howard fell by the wayside end by the age of 21 he was out of the first-class game.

Kimber caught up with him in Bendigo in up-country Victoria. We get a first-hand account of Howard’s difficulties.

“At one stage, there were headlines saying I was going to play for Australia,” he says. “I remember being about 20, and at the top of my mark at the MCG”. Instead of thinking, “How I am going to get out Jamie Siddons or Darren Lehman?” I’m thinking about a small group of men in the ground who are judging me. It wasn’t like that all the time, but when I was struggling this is how I felt. In the back of my mind I know the captain of my side doesn’t like me, and has told me to f**k off to Tasmania. The coach believes that, because I can’t bat or field, I am never going to be that useful. It was a dark time.”

Hang on, I thought to myself. What was that again? How did the disagreeable captain want Howard to get to Tasmania? (Dear reader, to spare your blushes I have replaced two of the letters in the original article with asterisks.)

I was reminded of a dear – alas, late – friend of mine who cut his journalistic teeth with the Liverpool Post back in the 1970s. The Post had a little collection of ‘spiked’ headlines – too accidentally inappropriate for publication. My favourite was a headline to a story about the Arctic explorer, Vivian Fuchs: ‘Doctor Fuchs Off to North Pole’. Another good one was the caption to a photograph of the Great Hall at Eaton Hall in Cheshire where the Duke of Westminster holds his balls and dances.

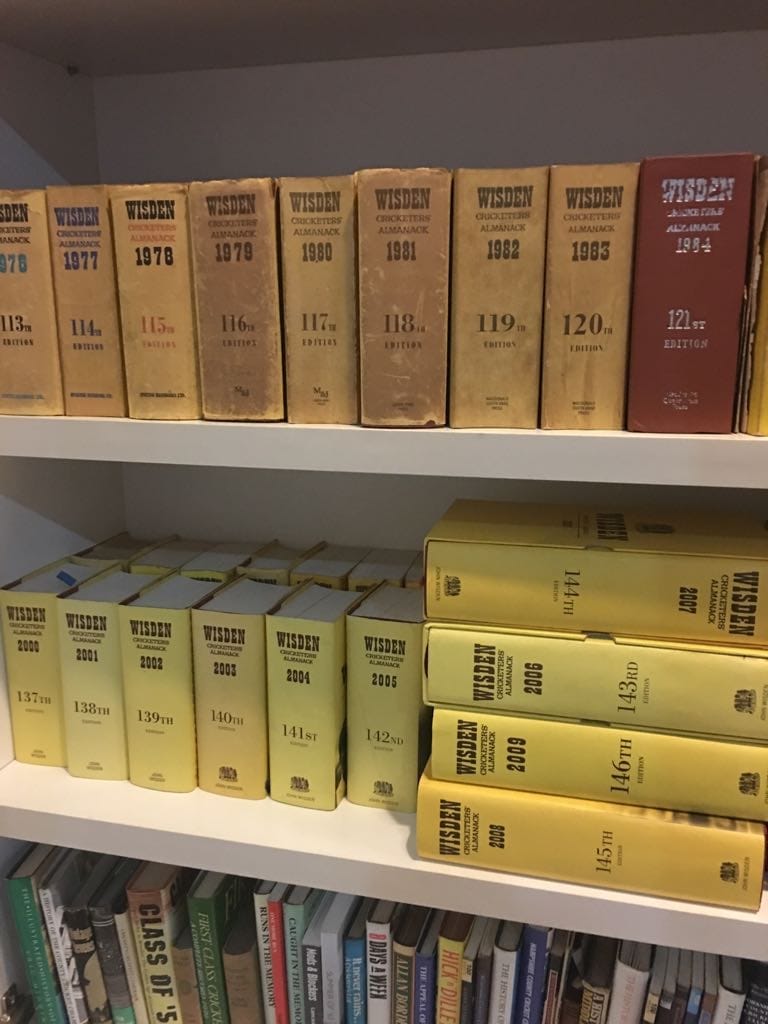

It’s a different world now, clearly. But can it really be the case that Wisden is ready for this, not to mention its readers? I suppose it is fair to say that Wisden is not traditional family entertainment. A 1500 page book with lots of numbers in it could hardly be so described. I was given my first Wisden at the age of eleven. Maybe that is unusual but it is certainly not unheard of. I suspect quite a lot of young teenagers like Wisden and their parents would doubtless be mortified to know that such breadth of language is to be found in its pages.

This was the first volume to be edited by Lawrence Booth. In the preface he writes, “our main task is unaltered: to record the previous year’s cricket, with an eye for detail, a nose for humbug and a taste for fun”. Well, yes, up to a point, Lord Copper. Robert Winder in his history of the Almanack, The little wonder, salutes Booth’s Notes to the 2012 edition for their “studied irreverence”. In a quite detailed description of the edition he makes no reference to Kimber’s article. I checked the index which has three references to language but none is a reference to bad language. (It is a good book but there is a howler on page 221*: sorry, but no book on Wisden should contain a howler.)

Of course part of the point about Wisden is that nobody ever reads the whole thing. Perhaps older editions are full of effing and blinding and Booth is just maintaining an ancient tradition. But I doubt it. A notable feature of the old editions was that the style was almost too magisterial and tight-lipped particularly the match reports. Take the opening words of the report of the match between Essex and Worcestershire at Chelmsford in May 1934, from the 1935 edition. “On Whit-Monday morning, Nichol, the Worcestershire batsman was found dead in bed – a sad event, which marred the enjoyment of the match but did not prevent Worcestershire gaining first-innings lead.” I sense a suppressed giggle coming on but it is not funny really. Nichol’s obituary, in the same edition, does not disclose whether he was married, with a young family, just that he appeared to be destined for great things as a cricketer. Life and cricket have changed beyond recognition. Today, if such a thing happened, the game would perhaps be abandoned. The Almanack, of course, has to keep up.

Whatever its blemishes, Wisden in an incomparably great book. The core of the book, the Test and county reports, the Notes (by nature variable), the essays on the “Five Cricketers of the Year” (debut, 1898), have always been essential reading. It was Matthew Engel, the greatest of modern editors who revolutionised the front of the book, introducing a wide range of articles by leading writers. The obituaries – one of the few parts of the Almanack to remain anonymous – are consistently outstanding. Much has been written over the last 80 years about Sir Donald Bradman – including a marvellous tribute by RC Robertson-Glasgow in the 1949 edition. But for a lucid, informative, elegant and objective assessment of the Don, one cannot do better than the obituary in the 2002 edition. The book reviews, for many years contributed by John Arlott, remain, on the whole, consistently good. Even in the internet age, the Records section is indispensable.

In his classic essay, ‘The Pleasures of Reading Wisden’, written for the 1965 edition, Rowland Ryder said that if you are looking something up in Wisden, you will always find yourself picking up all sorts of other bits of information too. That, of course, is a peril as much as a pleasure. Once you have learned how it works, Wisden is the archetypal time-waster.

There is one Wisden in the Lord’s museum. It is the 1939 edition and it belonged to EW (Jim) Swanton, once the doyen of cricket correspondents. That Wisden was with him when he was captured by the Japanese in Singapore and remained with him in Burma and Siam (Thailand) for the next three years. The book was a priceless treasure and a major item in the unofficial libraries set up by prisoners of war. Loans were limited to six hours a time. “Thumbed by thousands in twelve different camps” wrote Swanton. The book had to be glued together with rice paste.

Swanton fared little better himself. His father went to meet him at Waterloo station when he got back from the war and walked straight past him on the platform, unable to recognise his own son.

* The England all-rounder Len Braund – did anyone ever call him Leonard except at his christening? – played for Somerset, not Yorkshire. A quick check in, er, Wisden would confirm the point.

The article was published in ESPN Cricinfo: http://www.espncricinfo.com/thestands/content/story/688737.html