This article was originally published in Scoreline magazine.

English cricket lost two great servants in April with the passing of Raman Subba Row and Derek Underwood.

Raman Subba Row, had been, at 92 the oldest living England cricketer. Born in Streatham, London, to an English mother and Indian father, he was educated at Whitgjft and Cambridge where he was a near contemporary of Peter May. He took five for 21 with his leg breaks in the Varsity match of 1951 and made 94 in the 1952 match. In 1954 he got into the Surrey side ahead of his contemporaries Ken Barrington and Mickey Stewart but joined Northamptonshire in 1955 and, after missing two seasons because of National Service, played for them until he retired to go into business at the end of the 1961 season, and was captain from 1958.

He was a tall, aggressive left-handed batter. He was not the somehow typical elegant and languid left-hander. He had a slightly cramped and awkward style but he made up for this with timing and placement and a keenness for running quick singles. He had a penchant for big scores. He made 260 not out against Lancashire in 1955, and in 1958 scored the county’s first triple century, exactly 300, against Surrey at The Oval, putting on 376 for the sixth wicket with Albert Lightfoot (who passed away In 2023). He made his Test debut against New Zealand that year and toured Australia and New Zealand with MCC under May in 1958-59, but broke a bone in his thumb and played no Tests. His international breakthrough came on May’s tour of the Caribbean in 1959-60. Coming into the side for the fourth Test at Georgetown he made a second innings century batting at four. He kept his place for the next two English seasons till his premature retirement. Opening the innings with Geoff Pullar in the Ashes series of 1961, he attained the unusual record of scoring centuries in his first and last games against Australia. He headed England’s averages in that series. In all he played 13 Tests, averaged 46.85, and made three centuries and four fifties. He was 29 when he retired.

His contribution to the game, however, had only just begun. In 1968 he helped establish the framework for a local cricket league in Surrey, the basis of the league which exists today. Around the same time he got involved in the establishment of the Test and County Cricket Board (“ TCCB”), which took over the running of the English game from MCC, and which was in turn replaced by the England and Wales Cricket Board. He became chairman of the Surrey committee in 1974, serving until 1979. He was manager of the England – no longer MCC – side that toured India and Sri Lanka in 1981-82. In 1985 he became chairman of the TCCB, where he served for five years; in that capacity he played a major role in the formation of the International Cricket Council. For many years he acted as a match referee in international cricket.

Asked to name his favourite match, Subba Row not surprisingly nominated the Georgetown Test of 1959-60. The whole tour sounds amazing. Sunna Row told the story in Chris Westcott’s Class of ’59. When they arrived in Jamaica, Subba Row and his fiancée were provided with a new car by his friend, the great Frank Worrell (the pair had toured India with a Commonwealth side in 1953-54). At Georgetown, Subba Row was on 96 not out, and Worrell came up to him: “I think it’s time you had a full toss down the leg side” he said. (Alan Ross’ report of the match says Subba Row was progressing so slowly he seemed in danger of seizing up altogether.) Worrell was as good as his word, and Subba Row reached his century; Worrell had him leg before next ball.

Derek Underwood, who died at the age of 78 on 15 April was unquestionably one of greatest spinner of the post-war era, indeed of all time; among English spinners, only Wilfred Rhodes, Bobby Peel, and Johnny Briggs took more than his 88 Ashes wickets. He was also one of a kind, unique in his style and craft. There can be nobody alive who can remember watching Hedley Verity bowl. He must have been similar. The only modern comparison is Anil Kumble, who bowled his leg breaks at something like medium pace. Underwood had a seven-pace run-up, leaning forward as he advanced. It was somehow intense without being remotely athletic; the approach was noticeably splay-footed. He usually bowled round the wicket, when his run-up was very straight. When he bowled over, as he did to obtain his best Test analysis of eight for 51 against Pakistan in 1971, his approach was widely angled, coming in from the direction of mid-on to a right-hander. His pace meant that he could obtain a degree of bounce unusual for a spinner. He was a master of varying pace and flight even where there was little turn. When there was help from the surface he could be literally unplayable. Australians who are old enough still complain about the pitch for the fourth Test at Headingley in 1972 where the surface was affected by a virus; Underwood took six for 45 in the second innings. And from his earliest days he was phenomenally accurate.

Underwood was born in Bromley, Kent. A grammar school boy, he made his debut for the county at the age of 17, and in that season, 1963, he became the youngest player to take a hundred first-class wickets in a season. That is a record that will certainly never be broken. There was a feeling then that he was some sort of freak, that batters would find him out and that he would not enjoy such success in the future. Nothing could have been further from the truth. He took 100 wickets In a season ten times, with 157 in 1966 his best. By the time he was 26 he had a thousand first-class wickets.

On the uncovered pitches that prevailed in the first part of his career, Underwood was at his matchless best. Three times for Kent he took nine wickets in an innings, the best being nine for 28 against Sussex at Hastings in 1964. In 1967-68, playing for an International XI – which included two of his future England captains, Mike Denness and Keith Fletcher – against a Ceylon President’s XI at the Colombo Oval, he took 15 for 43, for many years the best figures in a first-class match in Sri Lanka.

He had made his Test debut in 1966 against Garry Sobers’ great West Indies team, taking one wicket in two games. It was in the Ashes series of 1968 that he first really made his mark, his seven for 50 in the fifth Test at The Oval enabling England to level the series on a sensational final afternoon; Underwood took the last four wickets for six runs in 27 balls. After that Underwood was an England regular, until his career was first interrupted by his signing for Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket and terminated by the South African rebel tour, leaving him stranded on 297 Test wickets, with only Fred Trueman of England bowlers ahead of hem.

He was not literally ever-present. Ray Illingworth, England captain from 1969 to 1972, often seemed to prefer Underwood’s near contemporary Norman Gifford. Underwood played in only two of the six summer Tests of 1971, Gifford or Robin Hobbs being picked for the others; that fourth Test against Australia in 1972 was his first of the series. But where there was anything in the pitch he was always the most dangerous. And his record overseas was exemplary. On Illingworth’s triumphant tour of Australia in 1970-71 he took 16 wickets at 32, more than anybody on either side apart from John Snow. In the first Test against New Zealand at Christchurch that followed that Australian tour he took six for twelve and six for 85. On the 1974-75 tour, which Australia won four-one, he took eleven wickets at Adelaide. Of his 17 wickets in the series, seven were Chappell’s, Ian or Greg. “Deadly” Derek Underwood was well named, “wrote Ian Chappell years later, “as I had a tougher time scoring off him than any other spinner.” The emphasis of Chappell’s comment is interesting: if there was a criticism of Underwood, it was that he could be too defensive-minded.

He enjoyed great success in the subcontinent too. On Tony Greig’s tour of India in 1976-77 he took 29 wickets at 17.55 apiece, better than any of India’s four venerated spinners and equalling Trueman’s England record for wickets in a series against India.

His best figures in a Test match, mentioned earlier, came at home, against Pakistan in 1974. The second Test at Lord’s was spoiled by rain and drawn but the damp conditions were made for Underwood, who took five for 20 in Pakistan’s first innings and eight for 51 in the second.

Pakistan only made 120 in their first innings and England responded with 270. Pakistan lost early wickets on the third day – Saturday – but then Mushtaq Mohammed and Wasim Raja gave what Wisden called masterly displays to take them to 173 for three at close of play. Then it rained, for much of Sunday, a rest day, and Monday morning. The covering appeared to be inadequate and the pitch was soaked. (The Pakistan manager, Omar Kureishi, accused MCC of negligence and incompetence.) Play resumed at 5.15 and Underwood, who had two wickets overnight, was soon operating. The pitch at the Nursery End seemed unaffected but at the Pavilion End it was a different story. After surviving for half an hour Wasim Raja was caught by David Lloyd off Underwood at short leg: 192 for five. Pakistan were all out for 226. Underwood took the last six wickets for no runs off 11.5 overs.

Underwood was not much of a batter. There is a celebrated picture of him avoiding a Michael Holding bouncer in 1976. That picture encapsulates how most of us would feel in that situation, with or without a helmet – in this case, of course, without: sheer terror. But against Australia at Leeds in 1968 he made 45 not out, then the highest score by an England number eleven in a Test. (This is yet another record now held by James Anderson.) He never made a Test fifty, but in 1984, playing for Kent against Sussex at Hastings, he made 111. The match was a tie; Underwood went in as nightwatchman on the first evening, 21 wickets having fallen that day. He retired in 1987.

In 2009 he served a term as MCC President, nominated, as is always the case, by his immediate predecessor, former England captain Mike Brearley.

As players, Subba Row and Underwood had little in common. But everyone who knew them seems to agree that each was a delightful and companionable individual; that is epitaph enough.

4 comments

Malcolm Merry

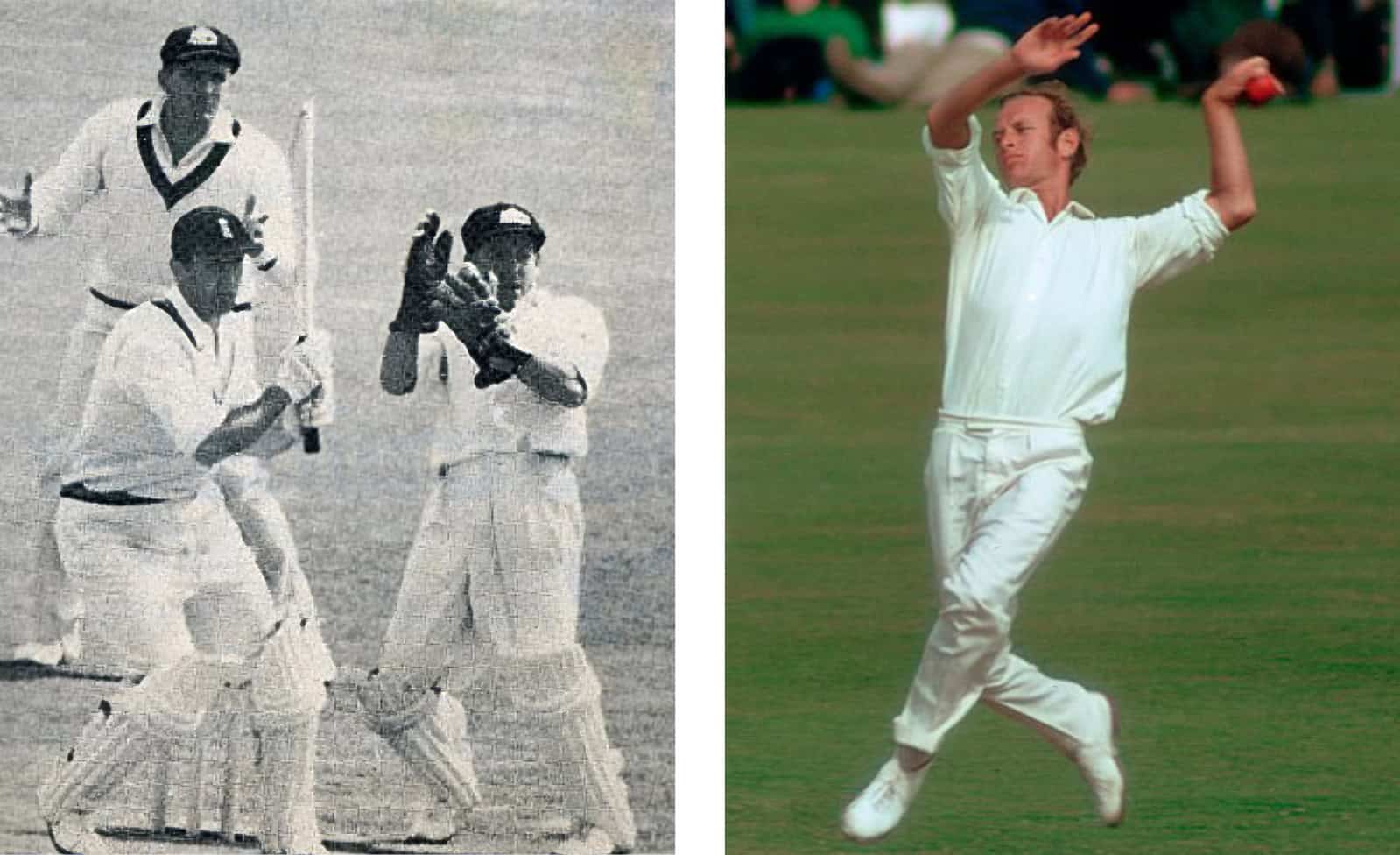

Evocative photo at the top of E.R. Dexter pulling an Australian bowler (Benaud?) during his 180 at Edgbaston in 1961. Subba Row, who also struck a century, would probably have been at the other end.

Malcolm Merry

Evocative photo at the top of E.R. Dexter pulling an Australian bowler (Benaud?) during his 180 at Edgbaston in 1961. Subba Row, who also struck a century, would probably have been at the other end.

David Edwards

Your usual fascinating writing, Bill. Full of interesting facts, especially about the extraordinary Derek Underwood. “Batters” persists but never mind!

Piers Pottinger

Very illuminating piece. My father met Subba Row for some reason and said he was utterly charming.