2019 promises to be a tremendous summer of cricket in England: the men’s World Cup, the men’s Ashes, the women’s Ashes; surely we’ve never seen anything like it before?

Well, yes actually. In the glorious summer of 1975, there was the inaugural men’s World Cup (officially the Prudential Cup) held only two years after the inaugural women’s World Cup. This was followed in the second half of the summer by a four-match Ashes series. And if the quality of cricket provided this year is anything like that on display in 1975, we are in for a treat.

The Prudential Cup was very different in a number of ways from its modern equivalents.

It comprised a total of 15 matches played on five days between 7 and 21 June. There were eight competing teams: the six Test teams, England, Australia, the West Indies, New Zealand, India and Pakistan, plus Sri Lanka and East Africa. They were divided into two groups and the two top teams of each group proceeded to the semi-finals.

So the tournament was much shorter than the modern versions, but the games were longer. Matches in the first three World Cups comprised 60 overs an innings. The 1975 final at Lord’s started at 11am and finished at 8.45 p m; it was the longest day of the year, so light was not an issue.

One-day international cricket was a relative rarity. The first such match had been played between Australia and England at Melbourne in 1970-71. Domestic one-day cricket in England, however, was very well established. The 65-over knockout competition, the Gillette Cup, had started in 1963. This was followed by the 40-over John Player Sunday League, played throughout the season by the seventeen counties, and the 55-over (knockout) Benson and Hedges Cup. (Yes, one of the differences was the proliferation of tobacco advertising.) This might have been thought to give the home side an advantage. But the eleven players who represented the West Indies in the final were all county professionals. Of their defeated Australian opponents, only Greg Chappell had played county cricket, for one season.

When Sussex won the Gillette Cup in 1963 and 1964 they did so with five fast and fast-medium bowlers, sometimes supplemented by the very occasional off-spin of Alan Oakman and Graham Cooper. West Indies’ attack in the final comprised Vanburn Holder, Andy Roberts, Keith Boyce, Bernard Julien and Clive Lloyd. Lance Gibbs, with over 300 Test wickets, played one match, against Sri Lanka, and bowled four overs. Spin just didn’t feature.

The two associate sides, Sri Lanka and East Africa (for whom Don Pringle, father of Derek, played), struggled and neither won a match. The competition’s highest score – 171 not out by New Zealand’s captain Glenn Turner (Worcestershire) was made against East Africa at Edgbaston. Sri Lanka put up a courageous display against Australia in their Group B match at The Oval. Facing Australia’s total of 328 for five (Alan Turner 101) Sri Lanka managed 276 for four, despite their two best players being consigned to hospital by the extreme pace of Jeff Thomson.

The Group A game between England and India at Lord’s on 7 June (the opening day, when three other matches were also played) was one of the most extraordinary of all World Cup matches. England made 334 for four (Dennis Amiss 137). India made no apparent effort to chase this admittedly daunting target. Opener Sunil Gavaskar batted throughout the 60 overs for 36 not out. They made 132 for three.

The most exciting of the group games was the Group B encounter between West Indies and Pakistan. Pakistan were a highly competitive and attractive side, and five of their top six batsmen were experienced county professionals. Batting first they made 266 for seven, with half centuries for captain Majid Khan, Mushtaq Mohammed and Wasim Raja. Saftraz Nawaz (four for 44) reduced the West Indies to 36 for three. When the eighth wicket fell on 166 it really did seem to be all over. But the highly experienced wicketkeeper Deryck Murray, who had last represented West Indies in England on Frank Worrell’s tour of 1963, saw them home with 61 not out. He put on 66 for the last wicket with Roberts. West Indies and England won all their group games, the former beating Australia by seven wickets at The Oval (Alvin Kallicharan78).

The semi-finals

Both semi-finals were played on 18 June.

West indies cantered to victory over New Zealand at The oval. At one point the Kiwis were 98 for one (Geoff Howarth 51) but the left-armer Julien dismantled their middle order and they were all out for 158. Gordon Greenidge and Kallicharan put on 125 for the second wicket and West indies won by five wickets in the 41st over.

The other semi-final, between England and Australia at Headingley, was a very different affair. Had it been a football match the score would have read something like Gary Gilmour 2, England 0.

The left-handed all-rounder (career record: 15 Tests, five ODIs) had the game of his life. Ian Chappell put England in in overcast conditions and Gilmour, unusually, opened the bowling with Dennis Lillee. England were reduced to 37 for seven as Gilmour swung the balk prodigiously to take six for 14. Captain Mike Denness and Geoff Arnold enabled the home side to limp to 93 (extras was third highest scorer with 14).

Amazingly, the game wasn’t over yet. Australia slumped from 17 for no wicket to 39 for six as John Snow and Chris Old took their turn to exploit the conditions. Enter the man of the moment to join Doug Walters: Gilmour hit a no nonsense 28 not out to see them home by four wickets. Incredibly, it was Gilmour’s first match of the tournament.

The final

The first World cup final, played on a perfect summer’s day at the game’s most famous and eye-catching ground, was adorned by a magnificent century from the West Indian captain, Clive Lloyd. West indies’ margin of victory, 17 runs, with eight balls left in the match, gives a fair indication that these were two evenly matched sides with West Indies just having the edge. The teams also boasted some of the greatest players ever to play the game.

Anyone who watched the game, even on television (like me) will remember a wonderful and often spectacular contest. One of the most extraordinary moments came early on when, after Ian Chappell had sent the West Indies in, opener Roy Fredericks hooked a bouncer from Lillee for six but simultaneously slipped on to his stumps and was out hit wicket. Greenidge made 13 in over an hour and when form batsman Kallicharan fell to Gilmour, the score was 50 for three; not a crisis exactly, but certainly a need to rebuild. This was when Lloyd joined the 39-year old Rohan Kanhai.

Kanhai took root – at one point he didn’t score for 11 overs – while Lloyd was at his imperious best. He reached his hundred off 82 balls with two sixes – one a magnificent hook off Lillee – and 12 fours. The pair put on 149 in 36 overs. Julien hit a few boundaries at the end and West Indies reached 291 for eight. Gilmour took five for 48.

Although the margin of victory was not large, and when last pair Lillee and Thomson were putting on 41 together anything seemed possible, the fact is that the West Indies were always just too far ahead. With that total to chase Australia needed a Lloyd and a Kanhai. But their largest stand was the second wicket partnership of 56 between Turner and Ian Chappell (top scorer with 62). The innings never really got going. An unusual feature was that no fewer than five batsmen, including Turner and the Chappell brothers, were run out, three of those dismissals being effected by the brilliant Viv Richards.

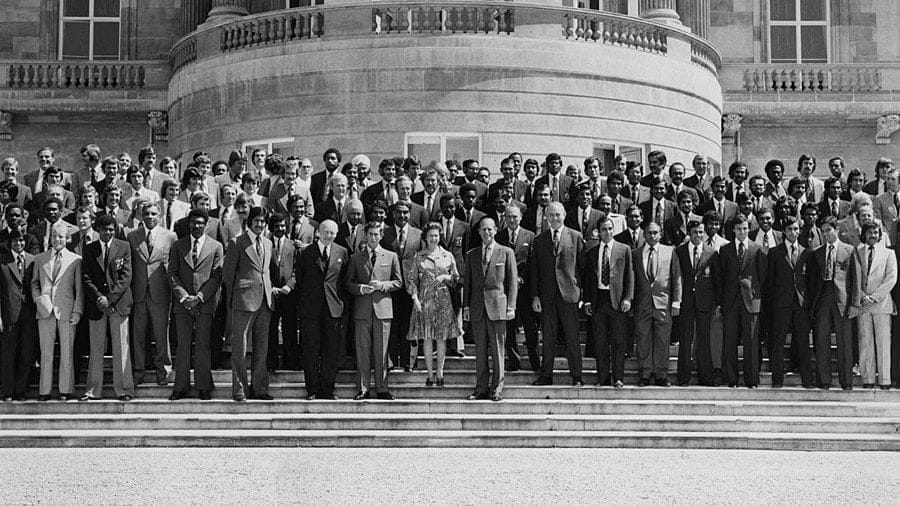

So it was Lloyd who accepted the trophy from the Duke of Edinburgh at the end of that incredibly long day. And the first World Cup demonstrated something that a number of its successors amply confirmed: the primary significance of captaincy in cricket, from a tactical perspective but also in the more nuanced sphere of “ leadership”.

One has lost count of the number of captains who have either jumped or been pushed after an unsuccessful World Cup campaign. But when you win…often a captain has played a genuinely inspirational role: think of Imran Khan in 1992 and Arjuna Ranatunga. Sometimes it is more a matter of leading from the front: Steve Waugh in 1999 and Ricky Ponting in 2003. And sometimes the result is a status little short of legendary: M S Dhoni in 2011.

With Lloyd it was perhaps a bit of all three. History will regard him as one of the greatest of all captains, leading his talented group of players from half a dozen different countries to a position of unparalleled dominance in the global game. But all that was a long way off in 1975. He was still a relatively new captain; his predecessor, Kanhai, was still in the side. Their next engagement, a Test series in Australia, resulted in a 5-1 defeat at the hands of the Chappells, Lillee and Thomson.

That was when Lloyd saw the future – four fast bowlers in a Test attack. And after the hiatus caused by World Series Cricket, it was he who made it happen. Of all the men who have stood on the podium and accepted the World Cup trophy, Lloyd remains the most impressive.