For a second year in succession, international cricket had a challenging time.

It didn’t win any matches or series. It didn’t come anywhere in the rankings, or win any awards. It wasn’t even the subject of an independent inquiry. But there is no doubt about the dominant feature of international cricket in 2021; as in 2020, it was COVID-19.

The year started reasonably normally with Test series being successfully completed in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Countries were learning from England’s successful “bio secure bubble” experiment in 2020. Particular heart was taken in South Africa, where the hosts not only comfortably beat Sri Lanka, but showed a sceptical world that international cricket could be staged in the Republic. England had recently cancelled a white ball series there. Australia were due in March. That series, however, was called off because the Australians declined to travel there.

How much had changed by the end of the year? On Boxing Day South Africa started what was their first home Test since the Sri Lanka series, against India, before empty stands at SuperSport Park. On the same day, sixty thousand spectators attended the first day of the third Ashes Test at the MCG. Spectators didn’t have to wear masks while they were in their seats but had to wear them if they went for a walk. There was a scare on the morning of the second day when there were a number of positive ART tests in the broader England group. The head of the Australia Cricket Board assured the media that the series would move on to Sydney and Hobart, and not remain in Melbourne, as had been rumoured, because of rising cases nationwide. Australia’s new captain, Pat Cummins, had missed the second Test at Adelaide, because of close contact with a positive COVID case. At year end, after England’s humiliating innings defeat at the MCG, it seemed that almost anything could happen, as far as governmental reaction to the virus was concerned, and its impact on the series. It was the same world all right; the mysterious way time works, always, but somehow especially during the pandemic, was making the “real” world seem like a distant memory.

The bio secure bubble was a godsend for the game’s administrators and fans but a mixed blessing for the players. England and India played more than anyone else and both employed “rest and rotate” policies at different times and in different ways. The system was especially hard on “all format” players; Jos Buttler apparently spent, altogether, an entire month in hotel rooms on his own in 2021. Mental health concerns were an aspect of Ben Stokes’ withdrawal from all cricket in the second half of 2021. Mental health problems of a different order saw three Sri Lankan players banned for eighteen months for breaching bubble protocol during their white-ball tour of England.

Australia took a different approach from England and India. They just stopped playing. Always eager to find an excuse not to play the “minor” Test countries, especially overseas, the pandemic provided the perfect opportunity. A number of teams, including England and New Zealand, found a variety of more or less spurious reasons for declining to tour Pakistan, despite that country having worked tirelessly to allay concerns about security.

Pakistan themselves toured England for some short format cricket and there were some positive tests in Eoin Morgan’s 50-over squad. What do you do, call the whole thing off? That’s what happened when there were positive cases in the context of four-day County Championship cricket in England. But oh no, there were television revenues to be protected. England just found another squad, and won.

Of course those revenues were nothing compared to the riches annually generated by the Indian Premier League (“IPL”). As the 2021 tournament got off to its scheduled start the pandemic was cutting a lethal and terrible swathe throughout India. Bringing joy to the television viewers, not to mention the sponsors, seemed a decidedly hollow argument for carrying on with the tournament, and it seemed only a matter of time before the virus hit the franchises, causing a mid- competition suspension and considerable chaos as foreign players scrambled for the exit door.

It was equally inevitable that the bean-counters would insist that the tournament was, somehow, completed.

This duly happened in September. “Going through the motions” wouldn’t be an entirely fair description but it was certainly a matter of compliance with contractual obligations rather than uninhibited sporting excellence. Did anybody really care about M S Dhoni’s Chennai Super Kings’ no doubt well deserved victory?

The Indian national team had been on a Test tour of England from mid-July. They had demonstrated a high degree of skill in all departments and as the two squads assembled for the final Test at Old Trafford, it seemed more likely than not that they would secure their first series win in a five-Test contest in England.

India had been concerned about the timing of this Old Trafford game from the start, asking for it to be shifted from the end of the series to the beginning. In the course of the fourth Test at The Oval, COVID struck the visitors’ backroom staff, the virus allegedly contracted at a book launch held for the benefit of the selfless and retiring national coach, Ravi Shastri. Nobody suggested that the game should be abandoned.

On the first morning of the Old Trafford Test, however, hours before the scheduled start, the Indians simply refused to show up. COVID, specifically concerns about possible quarantine in the event of additional cases, was the inevitable excuse. For a brief time it looked as though our learned friends were going to be involved in a complicated argument about whether the Test had been forfeited, but feathers remained relatively unruffled and the ultimate solution was to play a singularly meaningless fifth Test – that is the plan, nothing can be guaranteed these days – in the English summer of 2022.The fact that the match was not played in September 2021 meant that all relevant parties – that is to say, most of the Indian squad – were free to travel to the UAE in time to play in the obviously much more important remaking rounds of the IPL.

As far as actual cricket is concerned, priority should be given to the two global tournaments staged during the year. The final of the inaugural ICC Men’s World Test Championship was staged at Southampton in June between India and New Zealand. They had assuredly been the best two sides of the preceding couple of years, each invincible at home. The match itself was a fitting conclusion to the competition, a low-scoring affair evolving gradually and culminating in a gripping finale as New Zealand successfully chased down 140. Two of their longest serving players, skipper Kane Williamson and senior lieutenant Ross Taylor, were fittingly there at the end.

For four weeks between mid-October and mid-November the UAE staged the Men’s T20 World Championship. The ICC got this just about right in terms of length and there were some very entertaining games and some brilliant individual performances. There was one significant problem, which might have been an issue if the original hosts, India, had staged it (all the most lucrative tournaments now have to be staged by India, Australia or England), namely dew, which meant that the side batting second usually won. This was the case with both the semi-finals and the final.

All the early running was made by England and Pakistan, who dominated their respective groups. Buttler showed why he is one of the world’s most feared batsmen in white-ball cricket, but England, already without two iconic players in Stokes and Jofra Archer, were unlucky with injury. Pakistan’s leading players, especially openers Mohammed Rizwan and Bacar Azam, and pace bowler Shaheen Afridi, looked unstoppable. Their demolition of India, with a ten wicket win in their first game, was in many ways the sensation of the tournament.

New Zealand should never be written off in any international competition and it was they who put paid to England’s hopes in the first semi-final in Abu Dhabi, the coup de grace being delivered in a thrilling assault by left-hander Jimmy Neesham.

Australia made a slow start and for a while looked doubtful qualifiers. They peaked at just the right time, however, Matthew Wade fulfilling the Neesham role in a flamboyant innings in the second semi-final, at Dubai against Pakistan.

In the final, at Dubai, New Zealand seemed slightly out of sorts notwithstanding heroic batting from Williamson. Australia’s own hero was one of their more mercurial talents, Mitchell Marsh, who scored 77 not out off 50 balls. in a run chase of 173 for two.

The two most disappointing performers in this tournament were the holders, West Indies, and Bangladesh. They, however, produced one extraordinary Test match result. West Indies, minus five of their original Test squad, including then captain Jason Holder, because of concerns about COVID, were set 395 to win the first Test at Chittagong. They won by 7 wickets, the highest successful run chase in a Test in Asia, with debutant Kyle Mayers making a double century and fellow debutant Nkrumah Bonner scoring 86. Mayers’ achievement of scoring a double century on debut was emulated a few weeks later by Devon Conway of New Zealand against England at Lord’s.

Generally speaking, Test cricket continued to show why it is simply the most demanding and most rewarding format of a game which has never lost the art of re-inventing itself.

The year started with an extraordinary win by an apparently almost second string Indian side against Australia at, of all places, Brisbane, where the hosts had last been defeated by the West Indies in 1988-89.India won the series, and proceeded to beat England and New Zealand at home. Indeed, although New Zealand won the World Test Championship, it would be hard to deny a claim that India were the Test team of the year, after their performances in Australia and England. Their pace attack was second to none.

In their series in India after the T20 World Championship, New Zealand’s Ajaz Patel took ten wickets in an innings in the second Test at Mumbai, the city of his birth. The tall fast bowler, Kyle Jamieson, was a more consistently valuable addition to New Zealand’s bowling armoury.

Like most countries, Pakistan were formidable at home, and the deliciously eccentric Fawad Alam continued his remarkable comeback, with a conversion rate that would be envied by any of the Fab Four.

The Fab Four themselves enjoyed mixed fortunes. Williamson started 2021 as he had finished 2020, with a big double century, this time against Pakistan, at Christchurch. Subsequent returns were more modest but he remains probably the most universally respected man in world cricket. Virat Khoi and Steve Smith found themselves reduced to the status of mere mortals. This left centre stage to Joe Root who scored over 1, 700 runs in the calendar year, with six centuries, including two doubles. He has yet to conquer Australia, however. And his beleaguered England side have declined from “ not that good” to “ pretty dreadful” in the unofficial world rankings, mainly because nobody except him can make any runs.

Since 2015 the world’s number one ranked batsman has always been one of the Fab Four. Recently people have been talking up Babar as fit to rank with them. But in December someone else came up on the outside lane, as the idiosyncratic Australian Marnus Labushagne emerged as number one.

The single saddest aspect of Test cricket in 2021 was the presumed departure of Afghanistan following the return of the Taliban (though, to be fair, they did participate in the I C C Men’s T20 World Championship). It is certainly hard to imagine the women’s team reappearing any time soon. 2021 was a difficult year for the women’s game, because of COVID and related financial and logistical issues. There was one bright spot, however. The Hundred, created by the England and Wales Cricket Board to introduce cricket to a “ new audience” was, on its own terms, a relative success, though it is doubtful whether many people found it that different from T20 except that the names were sillier. But the women’s games were often played on the same day as the men’s, which meant that far more people watched them than usual, and they were often very enjoyable. This, among other things, broadcast the talents of two of cricket’s most exciting teenagers, India’s Shafali Verma and England’s Alice Capsey.

A notable individual departure from the international scene was Shastri, replaced as India’s national coach by the universally admired Rahul Dravid, a move that will be watched with great interest. For television viewers, it is likely that Shastri’s subtle and disinterested commentary style will no longer be a thing of the past.

Finally, 2021 took some distinguished cricketers from us. These included two distinguished England captains, Ted Dexter and Ray Illingworth, one of Illingworth’s chief lieutenants on his 1970-71 Ashes triumph, John Edrich, the stylish Indian batsman Yashpal Sharma, and three outstanding Australians in Colin MacDonald, Alan Davidson and Ashley Mallett. England lost her oldest living male Test cricketer – well two, Don Smith and Ian Thomson – and her oldest living female Test cricketer, Eileen Ash.

Three scribes, each different from the other and each supremely gifted, departed: the often humorous Martin Johnson, the West Country lyricist David Foot, and the Sage of Longparish, John Woodcock.

The year ended, however, on a note of joy and hope. One might not have thought so as an England supporter, but the trauma of England’s ignominious defeat in the Melbourne Test was transcended by the heart-warming success of 32-year old pace bowler Scott Boland who took six for seven to help win his debut Test. Boland was not simply a local boy. He was the second indigenous male Australian to play for his country. Since 2020 the player of the match at the MCG has received the Mullagh Medal, named after Johnny Mullagh, an indigenous cricketer who was the leading player on the Aboriginal cricket tour of England in 1868. Boland’s emergence from cricketing obscurity to win this award of this medal, and his rapturous reception from an adoring home crowd at this greatest of venues, helped to show why it is that, even now, perhaps especially now, with all its problems and imperfections, we love our wonderful game.

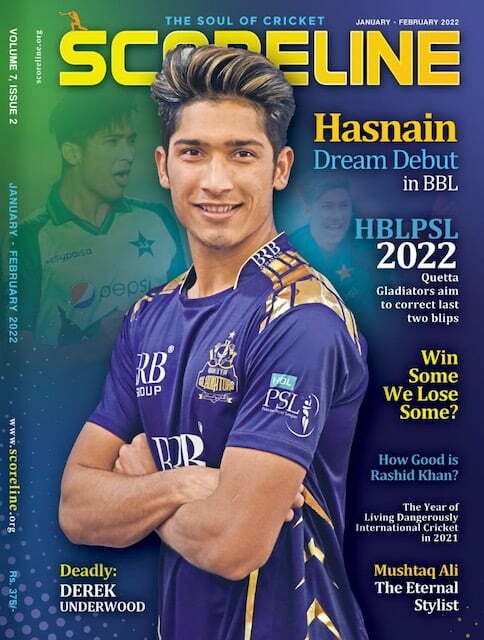

This article first appeared in Scoreline

2 comments

Bruce Freeman

Balanced and shrewd. If only that description could be applied to our national team….

Nambi

Excellent review. Thank you Bill