“Tom Graveney was the James Vince of his day.” Discuss.

Ridiculous, I hear you cry. Graveney was a master batsman, one of only 25 to have scored a hundred first-class hundreds, and with a Test match batting average of 44 in 79 matches. Vince averages just under 25 in 13 matches and has as much chance of making a hundred first-class centuries as I do.

By the time he was playing his fourteenth Test – against Australia at The Oval in 1953 – Graveney had made only one century, a mammoth 175 in his second match, against India in Bombay (Mumbai) in 1951-52. For a long time he did not seem really established in the side, even when he played a full series, as against Australia in 1953 and the West Indies in 1953-54 and, later, against South Africa in 1955 and Australia in 1958-59. By the time of his 35th match, the third Test against the West Indies at Trent Bridge in 1957, he still had only two Test centuries. He made 258 in that game; it seemed like a breakthrough innings, particularly when he made 164 against the same opposition two games later, but proved to be only partially so.

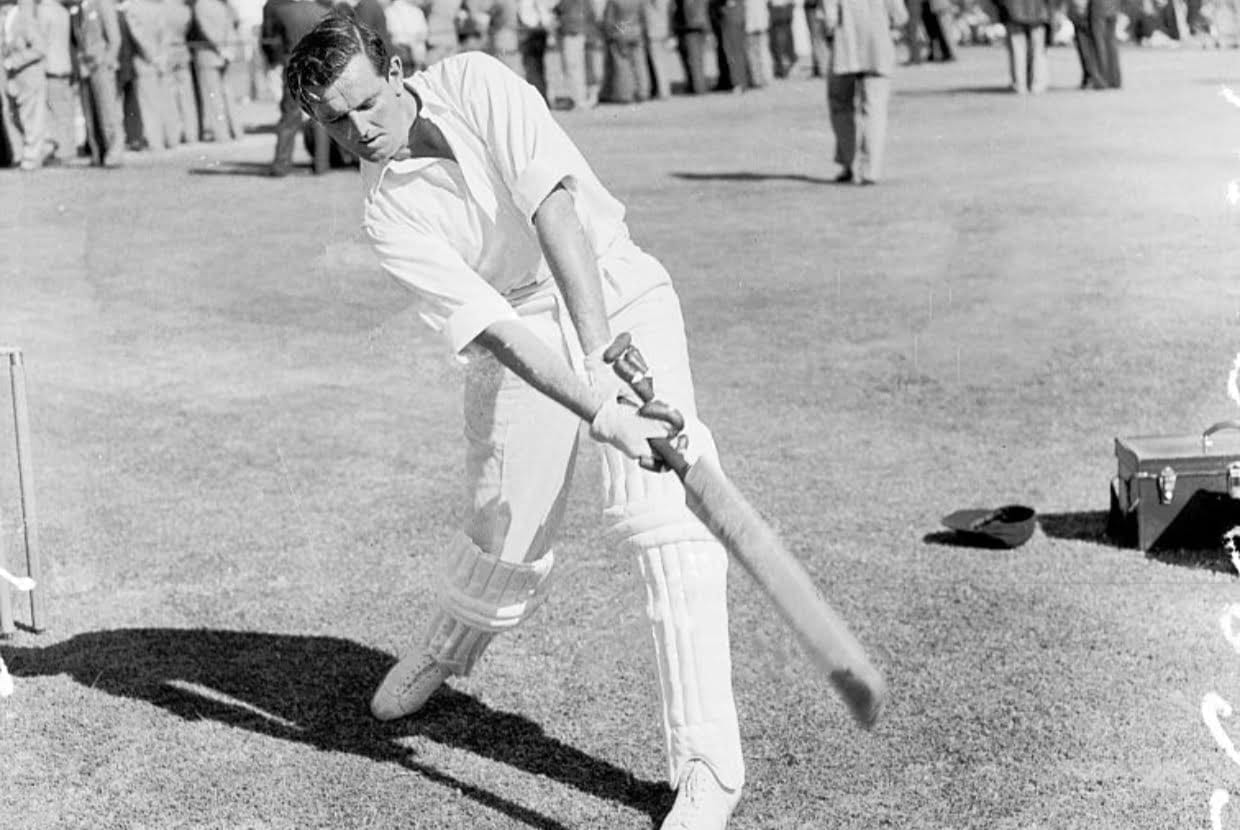

Vince might take some comfort from Graveney’s story; if he gets enough chances he might eventually take one of them. They are certainly comparable in terms of the spectacle they offer. Vince’s offside stroke-play has spectators cooing with awed delight. Graveney was similar. A tall man, ruddy cheeked and dark haired, he used his reach to great effect, playing almost exclusively off the front foot and driving sumptuously, especially through the covers.

With Vince, of course, you always know how it is going to end; the fatal nick to the keeper or slip cordon. That was never the case with Graveney; he was far too good a player. The fact is though, that, perhaps for the first two-thirds of his international career, he was felt to be not quite “there”. He was thought to be not quite out of the top drawer, particularly against pace, and to be vulnerable in pressure situations. Len Hutton, captain of England for much of Graveney’s early career, was said not to trust him (in a cricketing sense). Australia were always thought to set the ultimate test. Graveney’s record against them was decidedly patchy. He made only one century against them, in a dead rubber game at Sydney in 1954-55. He toured Down Under three times in all and spent substantial periods out of the national side after disappointing performances in 1958-59 and 1962-63. (Vince has not been selected since appearing against New Zealand in March 2018.) Alan Ross, in his wonderful account of Hutton’s triumphant tour of Australia in 1954-55 made a revealing comment while writing about Graveney and Reg Simpson (who played in three Tests between them) practising in Perth: “What magnificent net players these two are.”

In general, batting averages have gone up over the last few decades. In 1964, the season in which Graveney hit his hundredth hundred, thirteen batsmen averaged 40 or over in the English season; in 2017 the number was 47. But somehow this trend is not really reflected in the performances of the current English national side, where Vince’s record hardly stands out as being egregiously bad. In the top order the captain, Joe Root, is the exception with an average – steadily declining since he assumed the captaincy – of 49. The much-vaunted Jonny Bairstow averages 36; Jos Buttler, arguably the most talented sportsman in the squad, averages 35. With numbers like that you are not going to win many Test matches unless your bowlers are exceptional; England have been very lucky to have James Anderson and Stuart Broad.

It was very different in Graveney’s time. His long first-class and Test career coincided, or rather overlapped, with those of four other right-handed middle order batsmen of the highest class.

He is little talked about now, but many judges regarded Peter May as the greatest of all England’s post-war batsmen. A classical stylist, with a formidable defensive technique, on his day he could demolish any attack. He was an exceptionally strong driver, especially on the on-side. He averaged 45 in 66 Tests.

Colin Cowdrey was the most enigmatic of the five. At his best, he was as elegant and positive a batsman as one could wish for, but he could be subject to moods of tortured introspection. He outlasted all the others, becoming the first man to play a hundred Tests. Starting his Test career as one of the heroes of Hutton’s 1954-55 side, facing up to Lindwall and Miller, he finished twenty years later against Lillee and Thomson. He averaged 44 in 114 Tests.

Ted Dexter, an amateur and a captain, like May and Cowdrey, was genuine box office. “Lord Ted” had it in him to assume an air of total command and regal authority. He played two of what must be the finest short innings – meaning less than a hundred – in Test history, both in what turned out to be unavailing run chases: 76 against Australia at Old Trafford in 1961; and 70 against the West Indies at Lord’s in 1963. He averaged almost 48 in 62 Tests.

Ken Barrington was a chunky right-hander who as a young Surrey dasher made his England debut against South Africa in 1955. Failures in two games meant it was back to the drawing board and when he got back into the England side, against India in 1959, Barrington was a different player. Gritty and dogged with a rock-like defence he was an almost impregnable obstacle to opposition bowlers. In 82 Tests he had a phenomenal average of 58.

And then there was Graveney. He was older than the rest, established himself earlier in first-class cricket, and went on longer than all the others except Cowdrey. But, if one ignores Barrington’s early blip, the others eased into Test cricket while Graveney for many years seemed not quite at home.

This illustrious quintet never played in a Test match together. The window of opportunity for this to happen was admittedly narrow, basically between the 1958-59 Ashes tour, to which Dexter flew out as a replacement, and 1961, when May retired at the age of 31. For much of this period Graveney was either out of favour – following an unsuccessful Ashes tour – or unavailable.

As captain of Gloucestershire Graveney had led the county to second in the table in 1959, better than they had done for years. At the end of the following year, however, he was asked to step down as captain in favour of the amateur, Tom Pugh. Graveney left the county for neighbouring Worcestershire. Contractual disputes with his former county meant that Graveney had to sit out the whole of the 1961 season.

He won his England place back in 1962, scoring plenty of runs against Pakistan and securing a place on a third Ashes tour in 1962-63. But 116 runs in three Tests at an average of 29 just wasn’t good enough; his Test career appeared to be over.

Worcestershire had no complaints. In 1964 they won the County Championship for the first time; Graveney made 2,385 runs at an average of 54. Then in 1965 they won it again.

I went to Worcester a few times, later, in the 1970s, and saw Graveney make runs. It’s a cliché that the ground at New Road is one of the most beautiful on the county circuit. Yes, it’s alright. To get there, on a lovely early summer’s day, you might be lucky enough to pass through the bountiful Vale of Evesham. The old pavilion was quaint. If you were sitting in the right place, on the pavilion side, watching Tom Graveney bat, with the dramatic grandeur of the great cathedral – last resting place of two of the country’s most intriguing, and contrasting, leaders – King John and Stanley Baldwin – in the background across the Severn, it was impossible not to think: This is England.

Be all of that as it may, 1966 was a difficult year for the English national (cricket) team. The West Indies were touring under Gary Sobers. This was the last hurrah of the great side moulded by Frank Worrell. England were demolished by an innings in the first Test at Old Trafford (Sobers 161). Mike Smith was sacked as captain and replaced by Cowdrey. And Graveney was selected for the second Test at Lord’s. The match started on his 39th birthday.

West Indies batted first and made 269, Ken Higgs taking six for 91. Graveney’s return was an instant success. Going in first wicket down he made 96, as England secured a first innings lead of 86. They should really have won the game. The visitors were reduced to 95 for five in their second innings but Cowdrey’s unimaginative captaincy helped Sobers (163 not out) and David Holford put on an unbeaten 274 for the sixth wicket.

West Indies won the next two Tests to take a 3-0 lead with one game to go. Sobers was in irresistible form. In the series be scored 722 runs at an average of 103, as well as taking 20 wickets at 27. For much of the third Test, at Trent Bridge, the sides were pretty level, thanks largely to a fourth wicket stand of 172 between Graveney and Cowdrey, in extremely trying conditions. Graveney made 109 with 11 fours and a six.

Graveney did little in the fourth Test after which Cowdrey and a number of other senior players were sacked, and the Yorkshireman Brian Close was picked as captain. Perhaps the West Indies took their feet off the pedal. Whatever the cause, England won the match by an innings and 34 runs. This was by no means a foregone conclusion when they were 166 for seven, facing West Indies’ 268 (Sobers 81). But Graveney and wicket-keeper John Murray – himself no mean stylist – put on 217 for the 8th wicket, Graveney making 165 in six hours, and Murray 112. Then Higgs and John Snow put on 128 for the last wicket. West Indies were bowled out for 225 (Sobers 0).

Graveney had really, finally, arrived. In 1967, under Close, he enjoyed prolific form against India and Pakistan. In the first Test against the West Indies at Port of Spain in 1967-68 he made 118, with 20 fours, in what Wisden described as “a glorious exhibition of cultured batting”. Henry Blofeld, who has watched a lot of cricket, has described this as one of the great Test match innings.

He was solid in the 1968 Ashes, and captained England in the (drawn) fourth Test at Headingley when Cowdrey was injured. (Oddly enough Australia’s captain, Bill Lawry, was also injured, and they were led by Barry Jarman.)

He made his last Test century in 1968-69 against Pakistan in Karachi. He played in the opening match of the summer, against the West Indies and made 75. On the Sunday, however – always a rest day in those days – he played in an unauthorised benefit match. This was too much for the mandarins at Lord’s; Graveney’s Test career was over.

He carried on playing county cricket till 1972. His sometimes uneasy-relationship with cricket’s establishment seemed to have reached a satisfactory level of comfort when, in 2004, he became the first former professional to be named president of MCC.

I have two particular memories of him.

In 1968 I saw my first day of live Ashes cricket. It was the third day of the third Test at Edgbaston, in 1968, a drawn match much affected by the weather. England had made 402 in their first innings, the captain, Cowdrey, making a century in his hundredth Test, and Graveney making 96. Australia were bowled out for 226, Ray Illingworth and Derek Underwood taking three wickets each. We watched the second half of that innings, and then England came out to bat again. They lost a couple of wickets and Graveney came out to join John Edrich.

We were sitting square of the wicket. Graveney batted for an hour and a bit and made 39 not out. Nothing very remarkable about that, you might think, and of course it is true. But watching Graveney bat that day – I can see him now – the glory of his off side forward play – made me realise, however absurd it might sound, that batting of this style and quality transcended sport, and became something like an art form.

Years later, in 2001, I met him, well, sort of. I was with friends in Colombo, watching the third Test between Sri Lanka (won by another middle order batsman unrivalled by any current player, apart from Root; Graham Thorpe). Graveney was hosting a tour group. I saw him having a chat with the former Surrey and England batsman Micky Stewart (father of Alec). As cricket tragics will, I went and said hello. They were both absolutely delightful.

I reminded Graveney that he was the holder of an interesting first-class record. In 1956, in Newport, Glamorgan bowled Gloucestershire out for 298, of which Graveney made 200; it is the lowest first-class total to include an individual double century.

Graveney of course remembered it. He said that, as he was walking off at the end of the innings, the Glamorgan captain, Wilf Wooller, came up behind him.

“Graveney,” he said, ” that was the worst fucking two hundred I’ve ever seen.”

Bill Ricquier

Featured image: Ashes Test, 1954-1955. Tom Graveney, MCC team member, practices his batting at the nets in Perth, 11 October 1954. SMH Picture by Harry Martin. From WikiMedia Commons.

4 comments

Richard Sayer

Another excellent trip down memory lane. Thanks Bill.

Dave Allen

Very nice piece about a very nice man and a fine batsman, Bill. In his days travelling with the Worcs Committee I met Tom a few times at Hampshire and he told me another fascinating story. In July 1950, he played for Gloucs v Cambridge University at Bristol, when his captain was the amateur Basil Allen. Tom knew (Rev) David Sheppard and spent the previous evening with him – Sheppard opened for the University and scored a century, and as the players left the field, Graveney called out “Well played David”. Back in the pavilion, Basil Allen (no relation!) tore him off a strip, telling him he, a professional, had no right to address Sheppard by his first name. Why? Because Sheppard was an amateur! The bad old days …

Piers Pottinger

As someone who does not follow cricket this seems a well-argued piece to me. I met Ted Dexter once but it was at a golf course. He also excelled at golf.

David Edwards

This is a most excellent, well researched and wonderfully written article. Oh, the great names from the past that are there: Hutton, May, Sobers, Miller, Lindwall, other former greats and of course Graveney himself. I was fortunate to have seen all of these great cricketers and I will never forget them! Thank you Bill for bringing them back to life in such an impressive and detailed way. Great writing!