I remember listening to an interview with a batsman – a right-handed batsman, I just can’t remember who it was – who was struck by something as he practised a few shots in front of a mirror. “My goodness”, he thought to himself, or words to that effect, “it looks so much better left-handed.”

I recalled this as I read a typically entertaining and thought-provoking article by Jarrod Kimber. In “Are lefties really prettier? “ Kimber asks and sort of answers that question, concluding that they aren’t; there are plenty of ugly left-handers and plenty of pretty right-handers. It is not of course a scientific survey but Kimber pulls out some interesting facts and, as always, ventures down some intriguing highways and byways.

He points out that plenty of left-handed batsmen are naturally right-handed; he mentions Mike Hussey, Clive Lloyd and David Gower. Kimber says that according to Statsguru, 286 Test cricketers batted left-handed but bowled right-handed while 192 batted right-handed but bowled left-handed. Kimber calls these players “ambidextrous” but that does not seem quite right in the sense that as Kimber himself points out, in batting, in cricket, unlike baseball, the top hand plays a critical role so it is not so surprising that a naturally left handed person should be a right handed batter (to use a gender-neutral term) and vice versa.

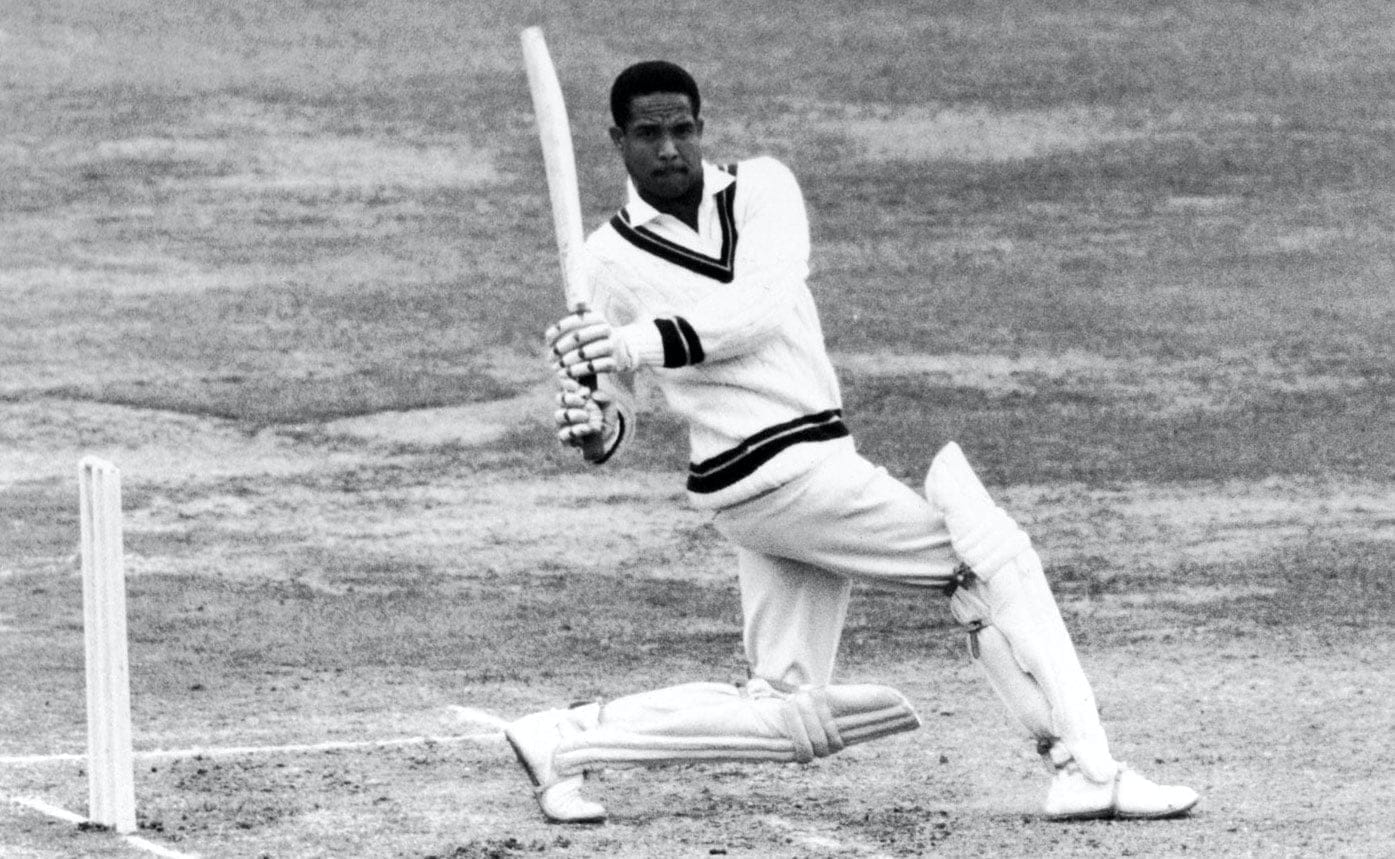

One curious point is that very few of the great all-rounders are ambidextrous in Kimber’s sense. W G Grace, F S Jackson, Warwick Armstrong, Ian Botham, Imran Khan, Kapil Dev, Clive Rice, Keith Miller, Trevor Bailey, Shaun Pollock, Jacques Kallis, Andrew Flintoff, Tony Greig, Lance and Chris Cairns, Angelo Mathews and Mushtaq Mohammed all batted and bowled right-handed. Gary Sobers (pictured), Wasim Akram, Frank Woolley, Mitchell Johnson, Shakib al Hasan, Ravindra Jadeja and Alan Davidson, all batted and bowled left handed. Ben Stokes, Richard Hadlee and Jack Gregory (batting left and bowling right) and Frank Worrell, Ravi Shastri and the Golden Age heroes Wilfred Rhodes and George Hirst (batting right and bowling left) are the only ambidextrous all-rounders with substantial Test careers.

Why do so few top keepers bat left-handed? This may seem an odd question to ask, given that the greatest keeper-batsman of all, Adam Gilchrist, was, in fact, a left-handed batsman. But how many others can you think of? Jack Russell, Ridley Jacobs… after that it’s a bit of a struggle. Back in the 1920s there was Hampshire’s George Brown, one of the game’s outstanding all-rounders. He was a pugnacious left-handed batsman, an aggressive right-arm fast-medium bowler, a brilliant fielder and a good enough keeper to play seven Tests in that role.

People often say it’s good to have a left-right combination to open the batting, as it upsets the bowlers but I’m not sure about that. It seems more sensible to pick the two best openers. History bears this out. Most of the best opening pairs have been either both right-handed or both left-handed: Jack Hobbs and Wilfred Rhodes or Herbert Sutcliffe; Len Hutton and Cyrill Washbrook; Andrew Strauss and Marcus Trescothick or Alastair Cook; Gordon Greenidge and Desmond Haynes; Matthew Hayden and Justin Langer; David Warner and Chris Rogers. There have been exceptions of course: Geoff Boycott and John Edrich; Bob Simpson and Bill Lawry; Mark Taylor and Geoff Marsh or Michael Slater; Graeme Smith and Herschelle Gibbs.

I was lucky enough to spend much of the late 1960s and the 1970s watching Hampshire. They had what must surely be one of the greatest opening pairs of all time in Barry Richards and Gordon Greenidge. We are moving back into Kimber territory now in that in terms of “prettiness” – not my choice – Richards and Greenidge, while utterly different, were both at the top of the class. Both, of course, were right handers. I can completely understand the – myth? – legend? – regarding left handers. I was lucky enough to be present to watch Gary Sobers’ last Test century, at Lord’s in 1973, and David Gower’s first Test innings, against Pakistan at Edgbaston in 1978. They were two left-handed geniuses; surely not too strong a word. Most respected judges who watched Richards rank him among the very best of all time despite the fact that he played only four Test matches. Watching him toy with county attacks – very strong county attacks – in the 60s and 70s was a truly remarkable experience. Greenidge of course was much the junior partner but became a hugely respected – and feared – opener for West Indies. The power and precision of his strokeplay made his batting a thrilling spectacle.

Kimber’s real message is that judgments like this are purely subjective and depend on all sorts of things apart from whether a particular batsman is left- or right-handed. Watching Hampshire in the 1970s emphasised this point. My two favourite players were not international stars. The first was Trevor Jesty, a highly effective all-rounder, middle order, right handed batsman and a canny medium pace bowler. It was the batting that caught the eye: Richards was his idol, and it showed. A team of the best England-qualified players who had never played Test cricket for their country would have to include Jesty. The other was David Turner, a nuggety left-hander from Wiltshire who everyone thought would play for England. But he never did. After a brilliant hundred against the 1972 Australians he suffered an eye injury and was never quite the same again. But I loved watching him bat, with his nudges and nurdles and occasional rasping cuts. Not conventionally “pretty” but deeply appealing. He played for the county for a quarter of a century; it was always his score I looked for first in the paper.

One thing which emerges from Kimber’s article is that there are now more left-handers than there used to be. He says that “historically” left-handers represented 20% of the Test batting population, as it were, but this has risen to 31% since the turn of the century. He observes that left-handers in the general population number around 11%

The last point may be a red herring, for the reason already given, that naturally right handed people might be inclined to bat left-handed. In general left handedness may be something that is not obvious in particular contexts. Sport is an obvious one. But everyday things can illustrate this. I am a left-handed Englishman who lives in Singapore. In the nature of things one not infrequently – well, before the dreaded virus – attends functions – wedding banquets, birthday dinners, business functions – where a lot of people sit down to eat a meal using chopsticks. Although I am not an especially observant person I am always keen on these occasions to see how many people are – like me – using their chopsticks with their left hand. The answer is far fewer than 12%.

I am sure Kimber is right when he gives the numbers for left handed batsmen in the modern game. But somehow it seems that there are more.

When England played West Indies at Lord’s in 2000 six of the West Indian top seven were left-handers (England, admittedly, had one, Nick Knight). In the equivalent fixture in 1963, of the 22 players who took part, only three were left-handed batsmen.

In Peter Wynne-Thomas’ The History of Cricket, published in 1997, there is a table showing a list of batsmen who had scored 4,000 Test runs at an average of at least 50. There were 15 of them, two of whom – Sobers and Allan Border – were left-handers. Today, of the top ten run-scorers in Tests, five are left-handers. It is not a complete match of course; in the list of highest Test batting averages there are only 2 left-handers in the top ten, Graeme Pollock and Eddie Paynter. But it surely illustrates the growing dominance of left-handed batsman, who have also made the three highest scores in Test cricket and four of the top five and six of the top ten.

Historically – by which I mean before when anybody reading this, including me, was born – left-handed batsmen were almost an aberration. It would be unusual for a Test team to include two. Normally, there would be the left-hander, and that would be it.

Looking at the list of highest run-scorers in first-class cricket, there are two left-handers in the top four: Frank Woolley (58,969) and Phil Mead (55,061) (There is only one other left-hander in the top twenty – John Edrich at 19 – but you can tell from the numbers that no modern player could get anywhere near them.)

Woolley and Mead were almost exact contemporaries, along with Jack Hobbs. Their careers take us back to Kimber’s point about batting aesthetics.

Woolley was what would now be called a star. He was very tall and striking and, as a batsman, exceptionally elegant. John Woodcock, in One Hundred Greatest Cricketers does not simply pick Woolley, he ranks him number 12. As with Gower, it was the majesty of his off-side play that struck the spectator. As Neville Cardus put it: “An innings by Woolley begins from the raw material of cricket, and goes far beyond. We remember it long after we have forgotten the competitive occasion which prompted the making of it.” As well as his runs he took over two thousand wickets with his slow left arm and took over a thousand catches. His Test record was not spectacular: 3238 runs at 36 and 83 wickets at 33.91, but he was pretty much an automatic choice from 1909 to 1927.

Mead was very different. Cardus never wrote lyrically about him but Cardus recognised his qualities: “Impregnable and imperturbable”, he called him. Mead scored more runs for Hampshire than anyone else has ever made for any single team. But he struggled to attract the attention of the selectors. He was not as eye-catching as Woolley but bowlers feared him more. R C Robertson- Glasgow, Cambridge and Somerset pace bowler, and one of the most felicitous of cricket writers, said: “[Mead] emerged from the pavilion with a strong rolling gait; like a longshoreman with a purpose. He pervaded a cricket pitch. He occupied it and encamped on it.”

He had played nine Tests before the First World War, scoring two centuries in South Africa in 1913-14: but his great moment came against Armstrong’s Australians in 1921. Before Don Bradman’s Invincibles of 1948 this was generally thoughtful to be the best side ever to have toured England. They won the first three Tests – Woolley made 95 and 93 at Lord’s and then, finally, the selectors turned to Mead. The last two Tests were drawn. Mead made 47 at Headingley and a massive 182 not out at The Oval, then the highest score by an Englishman against Australia in England. It was during this innings that Armstrong, fielding in the deep, reportedly borrowed a newspaper from a spectator “to find out who we were playing”. Gideon Haigh, in his biography of Armstrong, suggests the Australian captain engineered the selection of Mead – who, inevitably, made runs against the tourists for Hampshire – because he was so slow. This does not seem very plausible. Armstrong would surely have been more interested in winning the game than in not losing it. And Mead, whatever he looked like was, usually, no slouch: he scored a century before lunch on the second day.

Those were Mead’s only Tests in England. His overall record was pretty good; 1185 runs at 49.37 with four hundreds.

In 1928-29 Percy Chapman led one of the strongest ever MCC sides to Australia; they won the series 4-1. Selection of the touring party had been quite challenging, especially the batsmen, as there were so many well-qualified contenders (not a problem today’s selectors have to contend with). Both Woolley and Mead scored over three thousand runs in 1928. But there was strong support for the young Yorkshire left-hander Maurice Leyland. Why not take three left-handers then? Ha! Sorry, that doesn’t work.

It was Woolley who missed out. There was great umbrage in the Garden of England. The Kent amateur G J V Weigall described Mead as a “leaden-footed carthorse” and Leyland as a “cross-batted village greener”.

The tour was not a huge success for Mead. He played in the first Test at Brisbane – Bradman’s first game – and made 8 and 73. Then he was dropped.

There was an awkward moment at the start. This was Mead’s second tour of Australia. Like Hobbs and Woolley he had toured Australia with P F Warner’s highly successful side in 1911-12; Mead played in four Tests without achieving much. Hobbs and Woolley went back in 1920-21 and 1924-25, but of course Mead didn’t. So he returned Down Under after a 17-year gap,

At a civic reception for the MCC touring party the Lord Mayor of Brisbane reserved a special welcome for Mead: “We remember your father when he was here in 1911.”

3 comments

Alex Deverell

Fascinating debate on right or left hand bowlers/batsmen Bill – I’m deeply frustrated I can’t watch any to study right now in tedious lockdown to form my own opinion!

Rushad Udwadia

Thanks Bill. Please keep your e mails coming. They are a source of great joy always but much more so while locked down in Vancouver.

Bruce Freeman

An enjoyably wide-ranging view from the pavilion, Bill, but as a Hampshire supporter I was especially interested in your recollections of Jesty and Turner, not forgetting Richards and Greenidge, from the county’s most entertaining period.

How they won so little needs some explaining. At the risk of alienating the supporters of other counties, can you do so?