The curious paradox of Test cricket – that the less fitted its practitioners become to meeting the special challenges of the format, the more fascinating the actual games become – reached what must be its apogee in Durban in February when Sri Lanka won the first Test against South Africa by one wicket.

Chasing 304 to win, Sri Lanka’s ninth wicket fell at 226. Last man Vishwa Fernando, playing in his fourth Test came out to join the aggressive left hander Kusal Perera. Perera was well set (71 off 116 balls) having added 96 for the sixth wicket with Dhananjaya de Silva (48), when Sri Lanka for a while looked as though they might surprise South Africa. But three more wickets fell in the next six overs; nine down. Former South African fast bowler Makhaya Ntini, part of the TV commentary team during this domestic season, left the ground, assuming it was all over. Thousands of viewers and listeners around the World must have reacted similarly.

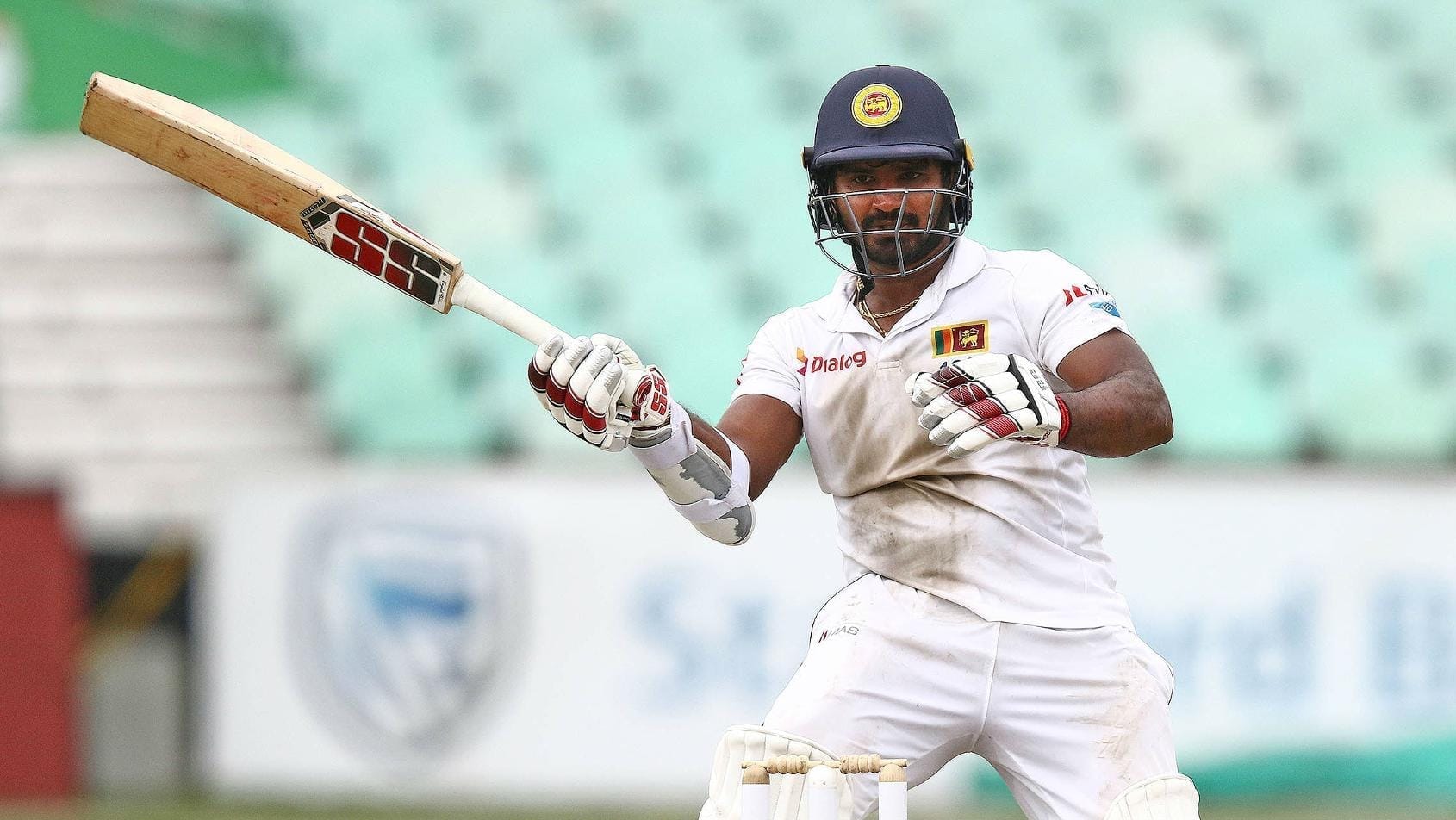

As we all know, Perera and Fernando put on 78 for that last wicket. Fernando made six of them. Perera made 153 not out, with 12 fours and five sixes. Theirs was the highest ever tenth wicket partnership to win a Test match.

It is almost impossible to make historical comparisons about these things but it is surely difficult to disagree with the assertion that Perera’s was one of the greatest, certainly one of the most memorable, of all Test innings.

Of course it might be argued that he had nothing to lose, and that in that sense there was little pressure on him. But that argument can only go so far. Perera had top scored in Sri Lanka’s first innings with 51 before trying something extravagant outside off stump to Dale Steyn and being caught in the covers. He has always been regarded as a risky sort of player. He had only scored one century in fourteen Tests before Durban. But he had scored a domestic triple century (with 14 sixes and 29 fours) so there was no doubting his potential. And in that second innings there was no sense of risks being taken. It was an astonishingly positive, fearless and mentally strong display. And in terms of “pressure” of course that could only have increased as time went on.

It is also necessary to consider the quality of the attack confronting Perera. Well, it doesn’t look too bad. Steyn, admittedly no longer in the first flush of youth, is universally recognised to be one of the greatest fast bowlers of all time; he had taken four for 48 in the first innings. Kagiso Rabada is probably the best fast bowler around now. Duanne Olivier is in the form of his life, contributing mightily to South Africa’s demolition of Pakistan – on the face of it much stronger opposition than Sri Lanka – earlier in the southern summer. Keshav Maharaj is a left arm spinner growing in confidence. South Africa were unlucky in that Vernon Philander, a potent new ball bowler suffered a hamstring strain during the game. But nobody could call that line-up second rate.

Perera’s uncompromising style is uncannily reminiscent of one of his great compatriots, the former opener Sanath Jayasuriya. But there is another great left-hander, very different technically but perhaps with some elements in common, who it is impossible to overlook in this context. The third Test between the West Indies and Australia at Bridgetown in 1998-99 was a must win game for the hosts and their captain, Brian Lara. Australia had a first innings lead of 161 but were bowled out for 146 in their second innings. West indies won, making 311 for nine; Lara made 153 not out.

In over two-thousand Tests, Durban was only the 13th to be won by one wicket.

One can understand why it is such a rare event. More often than not the side batting fourth in a Test match will be up against it. Every game is different but there is always excitement in a close chase. Durban and Bridgetown were similar in that there was a top batsman in at the end. It is different when there are two tail-enders in together, as in Melbourne in 1951-52, when Doug Ring and Bill Johnston took Australia over the line against the West Indies. But however different the build-up might be, once the ninth wicket falls there is always one irrefutable fact. Everyone knows it: the batsmen, the bowlers, the fielders, the crowd. It’s just one ball; that’s all it will take.

That is what made Durban so remarkable. Perera and Fernando batted together for 73 minutes, Perera facing 84 balls, Fernando 27.

If there is a formula for winning Test matches it will usually be, win the toss, bat first, make a lot of runs and don’t let the opposition back in. That is why the fourth innings is usually a challenge. As it happens, in Durban, Dinuth Karunaratne won the toss for Sri Lanka and inserted the hosts, apparently influenced by the overcast conditions. South Africa were bowled out for 235 on that first day but still got a first innings lead of 44, and Sri Lanka made the highest score of the match in the fourth innings.

There is also the fact that Sri Lanka were playing away from home. Of the 12 previous one-wicket Test wins all but three had been secured by the home side. The first two were in 1906 and 1923; the third was Pakistan’s victory over Bangladesh in 2003.

If anything, what happened next was even more extraordinary. Sri Lanka must have been expecting a strong rebound from the hosts. But Sri Lanka went on to win the second Test at Port Elizabeth as well, by the apparently comfortable margin of eight wickets.

This was another absolutely riveting contest, with South Africa, who won the toss and batted first squandering a number of potential winning opportunities. Basically, it was their batting which consistently let them down. This was despite the fact that Sri Lanka’s bowling attack was generally regarded as pretty toothless and lacking in depth as well as experience. But the old maestro, Suranga Lakmal bowled splendidly to undermine the Proteas’ second innings in Port Elizabeth while Fernando, the hero of Durban, bowled well throughout the series.

The game still looked in the balance on the third morning when Sri Lanka resumed their second innings on 62 for two, chasing 197 for victory. In fact the game was all over very quickly. Kusal Mendis (84) and new top order player Oshada Fernando (76) were magnificent. Mendis had had a quiet series. I have been saying for years in this blog that he is one to watch. In 2018 only two batsmen made a thousand runs in Tests: Virat Kohli and Mendis. He played some wonderful shots in this innings.

It is inevitable that this series win of Sri Lanka’s will be compared with the West Indies’ victory over England. Sri Lanka’s achievement is even greater than Jason Holder’s team’s. We all know that the West indies have had all sorts of problems. But they were playing at home, where even they are hard to beat, like all teams. Especially, as it happens, South Africa.

Sri Lanka became the first Asian side to win a series in South Africa. In fact, even if one just takes the period since readmission, only England and Australia have won series there.

And Sri Lanka appeared to be in an even worse state of disarray than when they lost three-nil to England in November. They had lost their best and most experienced player, Angelo Mathews, to injury. Their captain, Dinesh Chandimal, had been dropped after a collectively and individually catastrophic tour of Australia, where the batsmen had been sorely tested by a lethal pace attack. Sri Lanka’s own bowling attack could most politely be described as work in progress.

Now everybody was expecting more of the same. Even Karunaratne wasn’t expecting to win; he limited his team’s ambitions to being able to “compete”. Last time Sri Lanka were in South Africa they lost three-nil, the batsmen blown away by Steyn, Philander and Morne Morkel.

It all looks a bit different now though. In the two most recent series, the score is Sri Lanka 4, South Africa 0.

Bill Ricquier

Image from ICC website

2 comments

Bill Ricquier

Thank you Derek

Derek Hudson

Brilliant as always.