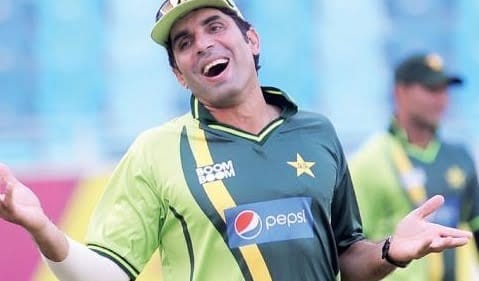

The simple answer is one that was only ever available to one team and is no longer available to them: appoint Misbah-ul-haq as captain.

In nine Test series between 2010 and 2016 Pakistan played nine “home” Test series in the United Arab Emirates, under Misbah’s captaincy, losing none and drawing four. There were twenty-four matches, of which Pakistan won thirteen and lost four, with seven draws.

“Home” has to be in quotation marks. The UAE is not Pakistan’s home. In reality, Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Sharjah are neutral venues. Test matches are played there because none of the other Test playing countries will agree to tour Pakistan because of concerns about security. The cost to Pakistan has been considerable, perhaps incalculable, not just in financial terms, but in the more nebulous but equally significant sense that they are unable to play in front of their own devoted home supporters. Attendances for Test matches in the UAE are often pitifully small.

It’s also worth remembering how things were when Pakistan effectively moved its cricket operations to the UAE in 2010 for a two-match series against South Africa. This was Pakistan’s first “home” series since March 2009, when a terrorist attack on a convoy including the Sri Lankan tram bus caused a number of fatalities and effectively put paid to the prospect of major international cricket being played in Pakistan for the foreseeable future.

Pakistan’s last Test match before the South African series had been at Lord’s in August 2009 against England. The game earned an unwanted and disturbing immortality because of the spot-fixing incident which ultimately led to three players, including the captain, Salman Butt, being sent to prison and banned from cricket for various periods.

The South African series had troubles of its own. The one-day series which preceded the Tests was thrown into controversy when the Pakistan wicketkeeper, Zulqarnain Haider, suddenly fled the jurisdiction after the fourth game – which he had helped to win – and turned up in London making somewhat vague allegations about match-fixing, and death threats to his family (who were in neither the UAE, nor in London, but in Pakistan).

The brouhaha surrounding Haider’s flight inevitably meant that expectations were low for the forthcoming Test series. There was a new Test captain – only the fifth in that calendar year – the 36 year-old Misbah. He had been out of the red-ball side since the tour of Australia which culminated in a heavy defeat in Sydney, so he was far from being a secure member of the team.

In fact, there were seven changes from the side that faced England at Lord’s, but there was one returning player almost as significant as Misbah. Younis Khan, who had announced himself with a Test century on debut against Sri Lanka at Rawalpindi in February 2000, and had established himself, along with Inzamam-ul-haq and Mohammed Yousuf, as one of the central pillars of Pakistan’s batting. But he had been mysteriously absent from the Test side for the previous fifteen months, and in the meantime had achieved little in the one-day side. Now he was recalled.

Few people could have anticipated the significance of the coming together of these two men. Misbah appeared to have been appointed captain because there were literally no other options (Younis had already had a go); he would have the added pressure of having to justify his place in the side. Younis, despite having scored a triple century in his last home innings – against Sri Lanka in Karachi – in the game before the terrorist attack – appeared to be on trial.

As it happened, they turned out to be one of the most successful batting combinations in Test history. Of the thirty-eight batting pairs who have made three thousand Test runs together, only four have done so at a higher average (68) than Younis and Misbah. They are Justin Langer and Ricky Ponting, Jack Hobbs and Herbert Sutcliffe, A B de Villiers and Jacques Kallis, and – wait for it – Yousuf and Younis.

Of course there was much more to it than the batting. Misbah, surely the most remarkable cricketer of his generation, turned out to be an outstanding leader who led his mercurial charges to be, albeit briefly, the number one Test side in the world. Younis, consistently under-rated as a player for the best part of two decades, contributed a degree of wisdom, intelligence and calm authority to the team that was as invaluable as his mountain of runs.

And, together, they turned the Gulf into Pakistan’s cricket fortress. Because the first thing you have to do to win – or at least not to lose – in the UAE, is to do what Younis and Misbah did so well: bat big, and bat long.

That first series, against South Africa, in which Pakistan were expected to do quite badly, seemed to set what might have been regarded as a template, in that there were two high scoring draws (it was a two-game series). The South African journalist Neil Manthorp said it “provided the entertainment value of a sleeping tablet”. In both games South Africa batted first and secured a substantial first innings lead: in the second game, in Abu Dhabi, they were put in and made almost six hundred. In both games Pakistan were fighting to save the match in the fourth innings. In Dubai, Younis made 131 not out and Misbah 76 not out. In Abu Dhabi Misbah made 58 not out having scored 77 in the first innings.

In fact, it turned out not to be a template at all. The next series, against Sri Lanka, was quite different, even though there were two draws out of three. Pakistan won the second, at Dubai, by nine wickets. Sri Lanka won the toss and batted but the pitch really had something for the faster bowlers and the visitors were reduced to 73 for five. They never really recovered from that, but it was an intriguing contest nonetheless. The third game, at Sharjah, was a more even contest but rain – yes rain! – intervened on the fifth morning and reduced the likelihood of a result. Misbah’s attitude to the potential run chase was indicated by his accumulation of nine runs off 86 deliveries.

In the first Test, Sri Lanka had secured a draw despite conceding a first innings lead of over three hundred. Kumar Sangakkara made 211 off 431 deliveries in their second innings: bat big, bat long.

Sometimes, it being Pakistan – even under Misbah – they just played badly and lost. That is really the only explanation for the loss to the West Indies in Sharjah in 2016. But Graeme Smith, captain of South Africa in that first series, surely had the right idea about how to win. This applies up to a point everywhere but – even though Misbah was fond of occasionally inserting the opposition – surely even more in the Gulf: win the toss, bat, get a pile of runs, and, after a respectful period of employment for the faster bowlers, throw the ball to your number one spinner.

The series against Australia in October 2014 provided an almost textbook example of this approach. In both Tests Pakistan batted first, scoring 454 in Dubai and 570 for six in Abu Dhabi. Younis made a century in each innings in Dubai. Both Misbah and Azhar Ali emulated him in Abu Dhabi, while Younis himself made 213 in the first innings. Misbah’s second innings century took 56 balls. Pakistan won by 221 and 356 runs respectively. Australia’s wickets were shared by a bunch of almost complete novices, at international level. The unorthodox off-spinner Saeed Ajmal had been banned by the ICC. Leg spinner Yasir Shah and seamer Imran Khan made their debuts at Dubai; Zulfiqar Babar and Rahat Ali were barely more experienced.

In November it was New Zealand’s turn. In Abu Dhabi Pakistan made 566 for three in their first innings (hundreds for Younis and Misbah) and won by 248 runs. But then things changed. The Dubai match was a finely contested draw and New Zealand won in Sharjah despite losing the toss and batting second. They responded to Pakistan’s 351 by scoring 690. Orthodox off spinner Mark Craig took ten wickets in the match as New Zealand won by an innings and 80 runs. Younis made five and nought, Misbah 38 and twelve. (The game was overshadowed by news of the death of Australian batsman Phillip Hughes.)

Craig’s success, as an orthodox finger spinner, was quite unusual in this period. Graeme Swann and Monty Panesar had very respectable figures on England’s tour in 2012 but they were completely outgunned by Ajmal. Often, though, it is leg spinners who shine, with Yasir to the fore. When South Africa won in Dubai in October 2013 the principal damage was done by Imran Tahir (born in Lahore). Devendra Bishoo took eight for 49 for the West Indies in Dubai in October 2016, causing a startling collapse. A year earlier at the same venue Adil Rashid took nought for 149 and five for 64 on debut for England.

Batting big and batting long have not always come easily to England, especially overseas. This in part explains their record in the UAE, where they have played six and lost five. In 2012, their batsmen were totally flummoxed by Ajmal and Abdur Rehman: in twelve innings between them, Kevin Pietersen and Ian Bell made 118 runs (“bat small, bat short…”). But England should probably have won in Dubai, where they bowled Pakistan out for 99 on the first day. England could only make 141 in reply and then Azhar and Younis made centuries; Pakistan won by 71 runs. (Oddly enough Tahir bowled them out for 99 at the same venue the following year but there was no recovery then.)

When England went back in 2015, there were two epic batting performances in the first Test at Abu Dhabi. Shoaib Malik made 245 in his first Test for over five years. Then Alastair Cook made 263 in 836 minutes – the third longest Test innings of all time. England almost scrambled a win at the end, ironically – or perhaps not – running out of time.

How have Pakistan fared in the Gulf when Misbah has not been in charge? In 2001-02 they beat the West Indies 2-0: Younis scored 153 and 71 in the second match. In 2002-03 they were humiliated in two games by Australia, losing both by an innings in the first of them they were bowled out for 59 and 53 (Shane Warne had match figures of eight for 24). All these games were played in Sharjah.

And then there was Sri Lanka in September 2017. Perhaps we should have seen it coming. Pakistan had hardly played any competitive cricket since their triumph in the Champions Trophy. Sri Lanka had played quite a lot, albeit much of it rather badly. Some of Pakistan’s leading players were below par, notably Mohammed Amir and Asad Shafiq. The absence of Sri Lanka’s great all-rounder, Angelo Mathews, turned out to be a blessing in disguise. By the end of the series captain Dinesh Chandimal was looking like a figure of real authority, not the tentative character he had appeared to be earlier in the year. Sri Lanka looked transformed in the field. For Sarfraz Ahmed, in his first Tests as captain, it was a steep learning curve. Too often it seemed to be a case of throwing the ball to Yasir and hoping for the best. And, of course, Pakistan were without Misbah and Younis. Sri Lanka know what it’s like: they are still coming to terms with the absence of Sangakkara and Mahela Jayawardene.

Sri Lanka have done well in the Gulf before. They drew a series in 2013 which some commentators thought they should have won. (The series contained one of the great rear-guard innings, 157 not out by Mathews in Abu Dhabi. And, of course, they had the redoubtable Rangana Herath, who just seems to love bowling against Pakistan.

How did they do it? Well, it was a simple formula really. Win the toss, bat; bat big, bat long, then throw the ball to your spinner. Twice.

The victory at Abu Dhabi was extraordinary. Sound batting from Chandimal and Dimuth Karunaratne took them to 419. Pakistan got a first innings lead of three and bowled Sri Lanka out for 138. In retrospect Niroshan Dickwella’s courageous forty not out was crucial. Sri Lanka won by 21 runs, old man Herath taking five wickets in each innings. It was Pakistan’s first defeat in Abu Dhabi.

It was more of the same in Dubai. Karunaratne, for so long a second innings specialist, compiled a magnificent 196 as Sri Lanka made 482. A substantial lead meant that the fact that they were dismissed for 96 second time round hardly mattered. Off spinner Dilruwan Perera took five wickets to secure a second famous victory.

It was a heartening win for Sri Lanka. They continue to have their issues. Kaushal Silva- who did much better in the Gulf in 2013 – and Lahiru Thirimanne have still not established themselves. And Herath cannot go on for ever.

For Pakistan. Well, perhaps it’s back to business as usual. Sarfraz obviously needs a little time. His task is overwhelming just to think about because of his various roles in the different formats.

But there is one thing that Sarfraz won’t be able to forget: it really is possible to lose in the UAE.

Bill Ricquier

Feature Image: Misbah-ul-Haq by World Cricket on Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

This article also appeared in scoreline.asia: