With the passing of Sir Everton Weekes in early July, cricket lost the last survivor of perhaps its greatest and most iconic of all batting associations. Of course there have been great opening pairs. There have been celebrated middle order combinations – Don Bradman and Bill Ponsford, Denis Compton and Bill Edrich, Kumar Sangakkara and Mahela Jayawardene. There were the Grace brothers, and the Mohammed brothers. But cricket has never seen anything quite like the Three Ws.

Frank Worrell, Everton Weekes and Clyde Walcott were born in a period of 18 months between August 1924 and January 1926 within a few miles of Bridgetown, the capital of Barbados an island nation in the Caribbean Sea, roughly the size of Singapore but with the population of a medium-sized English city. That this little place should have produced three such remarkable cricketers at the same time is remarkable. The delicious alliteration added to the aura.

Their records as batsmen were similar. Walcott made 3,978 runs in 44 Tests at an average of 56.68 with 15 centuries. Weekes made 4,455 runs in 48 Tests at an average of 58.61, also with 15 centuries. Worrell made 3,860 runs in 51 Tests at an average of 49.48 with nine centuries. Walcott and Weekes filled their boots in series against the weak bowling attacks of India and New Zealand respectively, series which Worrell either missed or did not do especially well in. Worrell took 69 wickets with his left-arm medium; Walcott kept wicket in the early part of his career and claimed 65 victims. Weekes was a brilliant fielder. Each made his Test debut against Gubby Allen’s 1947-48 MCC side; Worrell carried on after the others had retired, finishing his career after the triumphant England tour of 1963.

Apart from the fact that they were all brilliant right-handers, the Three Ws had almost nothing in common as batsmen. Worrell, tall and slim, was all style and elegance.

According to C L R James, the doyen of Caribbean cricket writers, he was in the line of great Barbadian stylists that started with George Challenor in the 1920s. Violence, on the cricket field or elsewhere, was not in his makeup. Walcott was a giant of a man, tall and immensely powerful, a natural driver of the ball. Weekes was short and stocky, very quick on his feet, and ruthless on anything that could be put away square of the wicket on either side.

There can be no doubt that of this remarkable trio, Worrell was preeminent. He died tragically young, at 42 in 1967, of leukaemia. In his Wisden obituary his great compatriot, Sir Learie (later Lord) Constantine said: “Sir Frank Worrell once wrote that Barbados…lacked a hero. As usual, he was under-playing himself. Frank Worrell was the first hero of the new nation of Barbados and anyone who doubted that only had to be in the island when his body was brought home (from Jamaica) in March 1967. There was a packed memorial service in Westminster Abbey: Worrell was the first cricketer to be so honoured.

For the 2000 edition of Wisden, the editor, Matthew Engel, invited 100 eminent judges from around the cricketing world to select their Five Cricketers of the (20th) Century. Of the 500 votes, 100, not surprisingly, went to Sir Donald Bradman. 90 went to Barbadian Sir Garfield Sobers (who were the ten eminent judges who did not think Sobers was among the top five cricketers of the 20th century? – I think we should be told). The other three were Sir Jack Hobbs (30), Mr Shane Warne (27) and Sir Vivian Richards (25). Worrell came sixth equal (with Dennis Lillee) with 16 votes. Neither Walcott nor Weekes received any votes.

With Worrell it is to a considerable extent his appointment and achievements as the first black captain of the West Indies that gives him his unique status; an iron fist in a velvet glove, as Scyld Berry called him. It might seem a ridiculous thing to say about a sportsman but it is not unrealistic to compare Worrell, in his specific context, with Nelson Mandela. It is difficult for us now to appreciate the dominance of the white population in the Caribbean territories as recently as the late 1950s. Mike Atherton alluded to this in his tribute to Weekes, whose background was humbler even than those of Walcott and Worrell, and who could not get a game in Bridgetown club cricket. The esteem in which Worrell was held as a man transcended his quality as a cricketer and contributed immeasurably to two Test series that, in terms of quality and excitement, rank with any before or since – Australia v West Indies in 1960-61 and England v West Indies in 1963.

Worrell was past his best as a batsman by the time he became captain, though he averaged 64 against England as late as 1959-60. But his status as a great batsman is not in serious doubt. His average was lower than his two great contemporaries and he scored fewer hundreds. But as always the figures can be a little misleading. The pitches in the Caribbean in the 1950s were, on the whole, batsman- friendly. Walcott, for example made 12 of his hundreds at home against varied opponents. Seven of Worrell’s nine Test hundreds were against England or Australia, easily the West Indies’ strongest opponents at the time. Interestingly, each of the Three Ws scored heavily against England in the Caribbean in 1953-54, scoring five centuries between them (they each made one in the first innings of the fourth Test at Port of Spain) but none had as high an average as England’s captain, Len Hutton (90.71).

Worrell came to prominence very quickly. As early as 1942-43 he put on 502 for the fourth wicket with opener Jeff Stollmeyer for Barbados against Trinidad. Two years later, against the same opposition, he broke that record by putting on 574 with Walcott, still the highest partnership in first-class cricket by any West Indian pair.

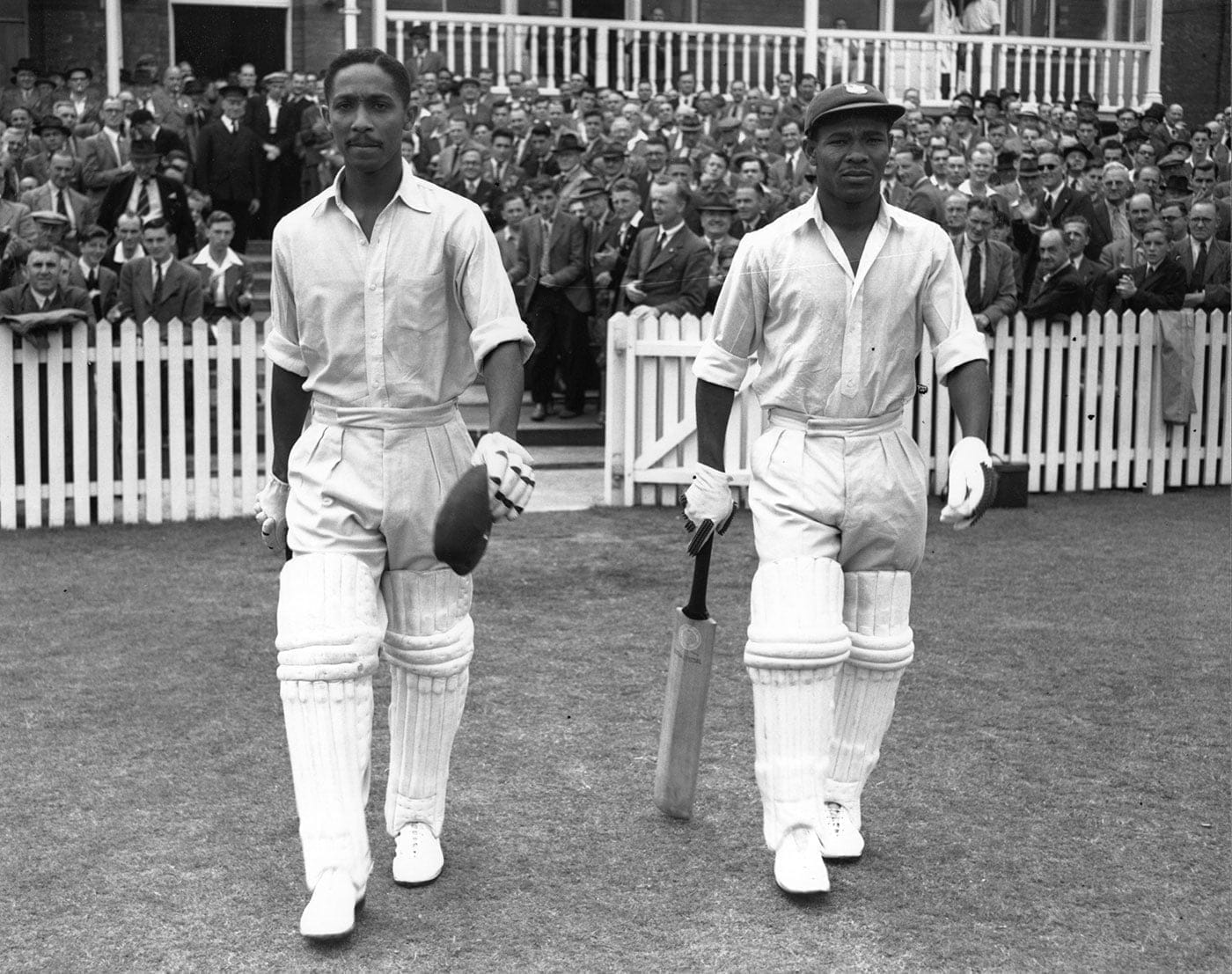

It was their individual and collective performance on the tour of England in 1950 that brought global recognition to the Three Ws. The visitors startled the cricketing world by winning the four-match series three-one. Weekes, Worrell and Walcott averaged respectively 79, 68 and 55 on the tour but in the Tests Worrell stood out, averaging 89.83, making two centuries (as did the opener Allan Rae) and scoring a magnificent 261 in the Third Test at Trent Bridge, putting on 283 in 210 minutes with Weekes (129) for the fourth wicket. In the next few years he lacked the usual consistency of Walcott and Weekes – they all struggled against Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller in Australia in 1951-52 when they made one century between them (Worrell’s 108 at the MCG in the fourth Test). When they returned to England in 1957, against a much stronger England bowling side, Walcott and Weekes made a half century each while Worrell made a masterful 191 opening, again oddly enough in the third Test at Trent Bridge.

According to E W Swanton, Walcott was the most exciting of the three, and, in home conditions the most devastating. His 168 at Lord’s in 1950 was said by Wisden to be the turning point of the series. Against the same opposition at home in 1953-54 he scored 698 runs at an average of 87.25. His most extraordinary achievement came in the home series against Australia in 1954-55 – Lindwall and Miller again (Australia won three-nil) – when he hit five hundreds and averaged 82. Richie Benaud said: “I have never seen a more powerful batsman than Walcott and when he was “going”, it was almost impossible to bowl a length to him.” In fact between March 1953 and June 1955 he made ten hundreds in twelve successive Tests. The Times cricket correspondent, John Woodcock said, years later, “Lord knows what he would do with a modern bat,” By this time he had given up keeping wicket: his size meant that he was never the most natural keeper, and he had back problems that led to him retiring after the Pakistan series in 1957-58. He was a good enough medium pacer to count Len Hutton, Tom Graveney and Neil Harvey among his Test match victims. After his playing career he went into business and gave years of distinguished service as a cricket administrator. In 1993 he became the first non-British chairman of the International Cricket Council. He died in 2007.

Weekes hit the ball as hard as Walcott but with less apparent effort. Intriguingly, he hit only two sixes in Tests, one of which was all- run; Scyld Berry has said that this was because, when Weekes was a boy, if he hit the ball out of the garden, it was lost. There is a case for saying that Weekes was the greatest of the Three Ws purely as a batsman. Simon Wilde described him as “the more complete player, possessing application, aggression and the vital killer instinct. In his authoritative One Hundred Greatest Cricketers, published in 1998, Woodcock ranked Weekes at 27, Worrell at 37 and Walcott at 38. (Woodcock put Sobers at 3, Richards at 8, George Headley (the “black Bradman”) at 21 and Brian Lara at 28.) Small of stature, sturdy and powerful, he was essentially a back-foot player. in stature he was not dissimilar to Bradman and was not infrequently compared to the great “The stocky executioner”, Swanton called him, “Bradman-like in the efficiency of his cutting and hooking”. Bradman himself said Weekes was the best West Indian batsman he had seen – better than Headley. Sobers, discussing David Gower, said: “If you call Gower a great player you will have to invent a new word to describe the all-time great players like Bradman and Weekes.”

After achieving little in his first few games in the series against England in 1947-48, Weekes was in danger of being dropped but, spared by injury to another, got a hundred in the last match. He followed this with four centuries in his first four Test innings in India in 1948-49, and was run out for 90 in his fifth. No other player has scored five hundreds in consecutive Test innings.

In the summer of 1950 he made over two thousand runs at an average of 79 with a highest score of 304 not out, and four other double centuries, and averaged 56 in the Tests. He made 206 against England in the fourth Test at Port of Spain in 1953-54, when Walcott and Worrell also made hundreds. He was in unstoppable form in New Zealand in 1955-56, making hundreds in three of the four Tests, each of which the tourists won.

He struggled with injury and illness in England in 1957 but showed his class in very difficult conditions at Lord’s, top-scoring with 90. He was the first of the three to retire.

Weekes must have been unusual, if not unique, among cricketers in being an international bridge player.

The triple effervescence: that was James’ description of this incomparable trio. That is hard to beat. The fact of their existence demonstrates the futility of selecting a “Best All-Time Eleven “or even “Best Post- War Eleven. No lover of West Indian cricket could contemplate a combination that did not include Weekes, Worrell and Walcott.

1 comment

Piers Pottinger

Fascinating stuff and told in a most compelling way.