Image: David Warner celebrating while playing for Australia. By Zaczac157 [GFDL or CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

David Warner did something genuinely remarkable when he made a hundred before lunch on the first day of the Sydney Test against Pakistan.

Only four batsmen had achieved this feat previously . Three of them were Australians who did it in Ashes Tests, in England. They were arguably Australia’s three greatest batsmen. The last time it had been done , only Misbah Ul Haq, of the participants in the Sydney Test, had been born.

When he started his Test career , Warner had played remarkably little first-class red ball cricket; he really was a T20 specialist. At his best Warner has not so much adapted to Test cricket as forced it to adapt to him. Misbah had raised the white flag almost within minutes of play being called on the first morning and Pakistan were never really in the match despite Younis Khan’s magnificent hundred in their first innings.

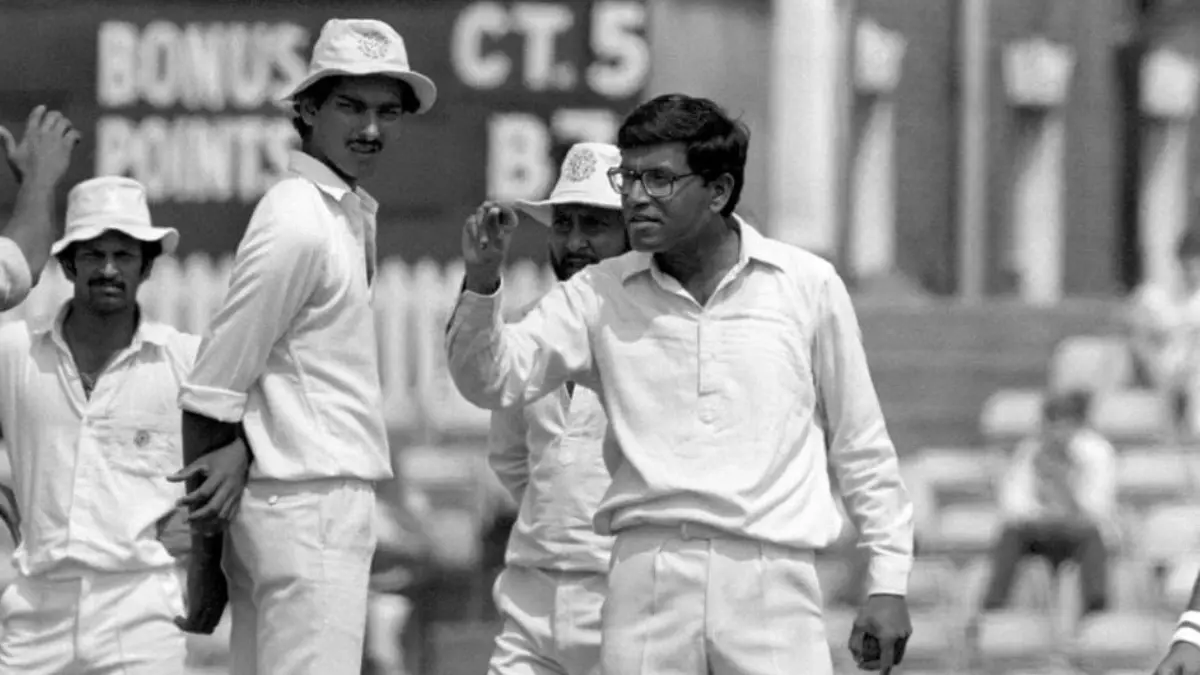

The last man to score a hundred before lunch on the first day of a Test had been a Pakistani, Majid Khan , in the third Test against New Zealand in Karachi in 1976-77. Pakistan had already wrapped up the series but the Kiwis had a decent pace Attack that included a young Richard Hadlee and Lance Cairns. Majid made his century off 74 balls in 113 minutes. The game was drawn.

Majid was a glorious batsman to watch at his best. Of his direct contemporaries , only Barry Richards, Greg Chappell and Lawrence Rowe were in the same class. With his off-white pads and his sun hat he seemed to have sauntered out of a sepia image from cricket’s Golden Age.

Before that , you have to go back to 1930 and the annus mirabilis of Don Bradman. He made a hundred before lunch on the first day of the third Ashes Test at Headingley, coming in at number three after Maurice Tate had removed opener Archie Jackson. But, of course, being Bradman, it wasn’t enough to get a hundred before lunch ; he made 115 between lunch and tea, and 89 in the final session. When he reached 200 Australia’s score was 268 for two. Bradman finished with 334, then the highest score in Test cricket. He hit forty-six fours and no sixes. The game was drawn.

Four years earlier, in 1926, at the same ground, England captain Arthur Carr won the toss and most unusually , for those days, invited Australia to bat first. This looked like a cunning plan when Tate, England’s greatest bowler of the era , induced Warren Bardsley to edge the first ball of the match tonHerbert Sutcliffe at first slip: nought for one. This brought Charlie Macartney to the wicket. He edged Tate’s fifth ball to second slip, Carr, who dropped it. Macartney reached a hundred out of 131 in 113 minutes. He made 151 in all , one of three centuries he made in the series. The tests were played over three days and although England followed on there was no time for Australia to force a victory. The Ashes was on a cusp: . Since the Great War Australia had won twelve Tests out of fifteen and England had won one. In 1926, the first four games were drawn, then England won the final game at The Oval.

Macartney was a totally different batsman from Bradman. The essence of Bradman’s barring was the elimination of risk. Macartney was all aggression. He used to say that it was a good idea to try to hit the ball back at the bowler’s head when you came in: they didn’t like it. Short and stocky he was a powerful driver but also played exquisite late cuts. Christopher Martin-Jenkins compared him in style to Brendon McCullum.

In his younger days he was more of an all- rounder but he gradually grew in status as a batsman. The Kent and England batsman KL Hutchings gave him his nickname of the Governor-General. At Lord’s in 1912, when he made 99, even the great Sydney Barnes could not keep him quiet.

The first man to make a hundred before lunch on the first day of a Test match was one of the genuine immortals, Victor Trumper. He did it at Old Trafford in the fourth Test of 1902 , one of the most famous of Ashes Tests. Trumper made his hundred in 113 minutes and Australia were 173 for one at lunch. They finished with299 and England made 262. Australia were then bowled out for 86, almost the only resistance coming from captain Joe Darling , who scored 37. England needed 124 to win. Their ninth wicket fell on 116 , and last man Fred Tate – father of Maurice – came to the crease. Previously he had dropped Darling east,y in his vital second innings. Now he was bowled for four as England lost by three runs. It was his only Test.

Trumper had a fine tour of England in that wet summer of 1902, making eleven centuries in all. But of no one is it more true than of Trumper that the figures are of little significance. Again, the contrast with Bradman could hardly be greater.

Trumper died aged 37 in 1915 so it is a long time since there was someone alive who could remember watching him play. But the image of Trumper – most graphically illustrated in the dramatic photograph of him by George Beldham – the leap out of the crease, the bat aloft, is extraordinarily vital. By all accounts he had all the shots , could be orthodox or improvise as the situation demanded and was utterly selfless.

Arthur Mailey , the great leg spinner , famously described bowling to Trumper in his first grade match in Sydney. He bowled him with a googly . ” I felt” , he wrote , ” like a boy who’d killed a dove “.

Bill Ricquier, 8/1/2017